About the map

The downside of the EU’s billions

The European Union is injecting billions of euros into the development of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe via the structural and cohesion funds as well as the European Investment Bank. The financial aid aimed at reuniting Europe and healing its Cold War divisions is necessary and laudable. Yet there is an unfortunate downside: as this map starkly illustrates, much of the development driven by EU money is reckless, destructive and ineffective. The potential of EU finance to deliver benefits is being unnecessarily undermined.

50 projects at a cost to EU funds of €10bn

This map displays 50 environmentally harmful and often also economically dubious projects being financed – or planned to be financed – by the EU funds and the EIB. The map covers the 10 new EU member states of Central and Eastern Europe and the two candidate countries, Croatia and Macedonia. The total estimated cost of the 50 projects is at least €22.0bn. Of this, €10.1bn stands to be paid via the EU funds, not counting the additional billions of euros in the form of loans from the EIB. All of this money could be used much more effectively, if only alternative solutions were considered properly.

Our aim: sound use of EU money

With this map, CEE Bankwatch Network and Friends of the Earth Europe are aiming to ensure that EU money does not cause damage but instead brings real benefits to the citizens of the CEE countries and promotes sustainable development. The big majority of the projects on the map have not received funding yet, which means that most of the environmental harm and money wastage can still be prevented. The governments and the EU must call a halt to such projects and properly examine alternative solutions.

Sources of information

The map is the result of an extensive investigation carried out by the national member organisations of CEE Bankwatch Network and Friends of the Earth Europe in cooperation with other non-governmental organisations. The information provided about individual projects is based on official documents such as operational programmes and environmental impact reports, communication with local citizen groups as well as independent expert studies. The map shows only a selection of the most significant and currently known projects. The number of projects displayed in each country reflects not only the quantity of problematic projects but also the capacity of non-governmental organisations to identify and research them. That is why, for example, there are only a small number of projects displayed in Romania.

Types of projects

The map comprises three categories of projects:

-

6 approved projects, for which EU/EIB money has already been authorised and that, in some cases, are already under construction or completed

total cost: €2.7bn; cost to EU funds: €0.5bn - 35 planned projects, that are listed in the national plans for EU funding in the 2007-2013 period or are planned to be financed by the EIB

total cost: €14.5bn; cost to EU funds: €9.0bn - 9 potential projects, that are not officially listed in the EU funding plans or in the EIB pipeline, but are being seriously considered for EU or EIB financial support

total cost: €4.8bn; cost to EU funds: €0.6bn

The most common types of projects on the map:

- 14 motorways and expressways, ineptly routed through residential areas or valuable natural sites

total cost of the problematic sections: €10.5bn; cost to EU funds: €6.4bn - 18 waste incinerators, promoted at the expense of more economical and green alternatives, such as waste prevention, recycling and composting

total cost: €2.0bn; cost to EU funds: €1.2bn - 8 inland navigation and other water management projects, involving the artificial regulation of rivers or lakes with damaging impacts on natural ecosystems and other functions of these water bodies

total cost: €1.3bn; cost to EU funds: €0.5bn

What is controversial about the projects?

- All the projects on the map are environmentally damaging – they will cause significant harm to the natural or human environment or undermine environment-friendly alternatives.

- The projects are also often economically dubious – their costs are higher than their benefits or they crowd out more cost-effective alternatives.

- Many of the projects are legally deficient as they breach national or EU legislation (e.g. with regard to environmental assessments or Natura 2000) and some of them are already the subject of legal complaints and court cases.

- A lot of the projects face public opposition, usually led by people living in their vicinity who would be most directly affected but often also including broader concerned public.

Changes since the 2006 version of the map Two years ago, CEE Bankwatch Network and Friends of the Earth Europe published the first version of this map (www.bankwatch.org/billions/2006). What is new in this updated edition?

- The EU’s funding plans for the period 2007-2013 have been finalised and approved, providing more clarity on the planned projects.

- The new map also includes projects financed by the EIB. Despite their different set-ups, both the EU funds and the EIB are public financial mechanisms and often co-finance the same projects, hence there is no reason to separate them.

- As a result of the above changes, there are a greater number of projects on the current map: 50, up from the previous 22.

- Some of the previously planned controversial projects displayed on the 2006 map have been withdrawn and are fortunately no longer being seriously considered for EU financing in the 2007-2013 period (e.g. the Danube-Oder-Elbe and Danube-Tisza canal projects).

Solutions

A systemic problem requires systematic solutions

This map shows that controversial projects are unfortunately not limited to a few isolated exceptions. If nothing changes, EU money will bring not only many benefits by the end of the 2007-2013 period but also substantial environmental devastation throughout the region and a significant share of the funds will be spent ineffectively. This would be a lost opportunity. Moreover, as all EU projects must be visibly marked with an EU logo, people are likely to hold the EU responsible for unpopular projects.

An unnecessary price for development: alternatives are available!

The controversial projects on this map are not the results of an “inevitable trade-off” between economic development and environmental wealth. Alternative solutions exist – be it simply a different route for a motorway or a conceptually different solution, such as separating and recycling waste instead of incinerating it. The potential devastation outlined in the map can be avoided. What’s more, many projects that harm the environment are economically irrational, while the greener alternatives are often more economic.

Prevention: alternatives require a level playing field

The way to prevent the problems highlighted by the map is simple: the different project alternatives or solutions must be impartially assessed, compared and consulted with the public in order to select the best options from economic, environmental and functional points of view. This should also be the basic condition underlying the EU’s and the EIB’s approval of money for the projects. Regrettably, time and time again this does not happen.

Why are alternatives still ignored?

EU legislation formally requires authorities to make a cost-benefit analysis and environmental impact assessment, including consideration of alternatives and a public consultation for every major project. So how is it that problems persist? Typically, the authorities pre-select a particular project variant and then push it through at any price. The results are poor quality environmental assessments, disregarding of alternatives, and merely pro-forma public consultations. The underlying reasons range from a “builder mindset” and disdain for environmental values, to the undue influence of various companies or politicians with vested interests, all the way to outright corruption.

Responsibility of the European Commission and the EIB

The Commission and the EIB are ultimately responsible for the use of EU public resources. Every time they approve a deficient project, national authorities and project promoters draw a lesson that even badly prepared projects can count on EU funding. The Commission and the EIB should not give a green light until alternative solutions are properly assessed. The new EU agency JASPERS, tasked with assisting new member states to prepare major projects for EU and EIB funding, should be used to ensure a fair and participative project preparation process from an early stage.

Ensuring smooth absorption of EU funds

Inadequate environmental assessments and the ignoring of alternatives by the authorities can lead to court challenges, project delays and higher costs, as seen for example in the cases of the D8 motorway in the Czech Republic and the Via Baltica in Poland. Careful and rigorous development planning, as opposed to reckless project preparation, is necessary to ensure that CEE countries can in fact spend the full sums of EU funding available.

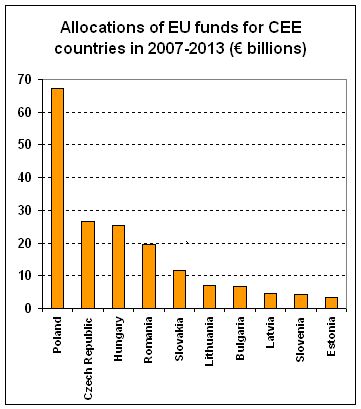

EU funds and the EIB

Structural and cohesion funds

With €347bn allocated for the 2007-2013 period, the structural and cohesion funds represent more than a third of the EU's budget. Just over half of the total – €177bn – has been earmarked for the ten CEE new member states. These countries have been receiving EU funds since 2000, but the annual volume has more than doubled since 2007. Their governments will have to add further billions of euros from their own budgets, as the EU only pays up to 85% of each funding programme. The funds can be used for all kinds of projects: transport infrastructure, sewage treatment plants, new technologies for enterprises, research, education, etc. The candidate countries such as Croatia and Macedonia receive much less – but still significant – pre-accession funding from the EU.

European Investment Bank

The EIB is the EU’s public bank, which lends money on favourable terms to projects that should support EU policy objectives. The EIB provides loans to EU member countries and often also co-finances projects in tandem with the structural and cohesion funds. With a total annual portfolio of almost €53bn in 2006, the EIB is responsible for almost double the amount of investments made by the World Bank and has recently been increasing its operations outside the EU.

Misuse of EU funds

According to the EU Court of Auditors, at least 12% of the structural and cohesion funds, or around €4bn, was spent erroneously in 2006. Irregularities in accounting, however, are only part of the problem and it is far from certain that the remaining billions were spent correctly. Our research in Poland revealed that projects applying for EU funding are often arbitrarily selected by regional politicians and officials who, without justification, override project evaluations done by independent experts. In Hungary, a local politician was caught on camera in 2007 explaining to an entrepreneur how applicants for EU funds are expected to secretly return part of that money to the ministry if they wish to get the subsidy. In Lithuania, there is talk about a widespread "10% rule" for EU fund applicants. If EU funds are to be spent effectively, there needs to be a major improvement in not only accounting controls but also in project prioritisation and overall transparency standards. In this way EU funds could actually help reduce overall corruption in the CEE countries by spreading good practice throughout their public administrations.

Climate change and energy

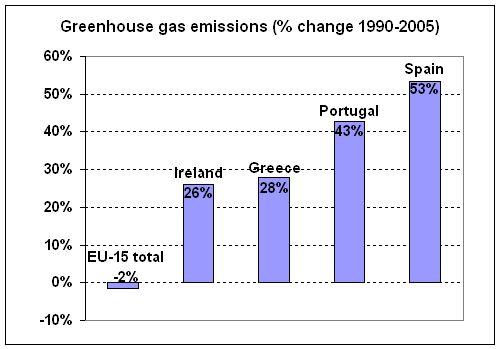

A history not to be repeated

The record of EU funds on climate change has up to now been an unequivocal failure. The four countries which have so far received the most EU structural funding (Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain) have also witnessed by far the greatest increases in greenhouse gas emissions in the EU. While the blame cannot be wholly pinned on EU funding, EU money has undoubtedly contributed to the trend. Ensuring that this scenario is not repeated is in the interests of the CEE countries and is essential for meeting the European objectives for limiting climate change.

Source: European Environment Agency, 2007

EU money must support the shift to an energy- and resource-efficient economy

World fuel and energy prices have soared recently and are set to remain high. The CEE countries cannot afford to repeat the development mistakes of Western Europe. EU money in the new member states has to be directed towards energy efficiency, resource use reduction and recycling, eco-friendly technologies and sustainable mobility. Such development will reduce dependence on imports of raw materials and will accelerate technological innovation and job creation.

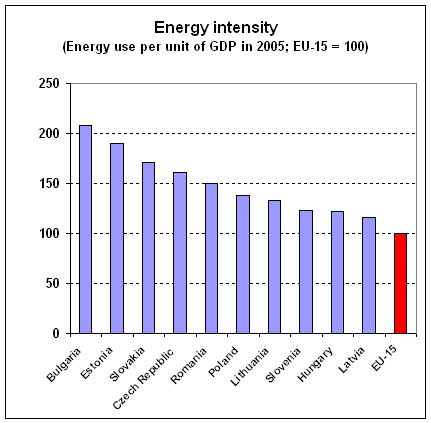

Energy: boosting efficiency

It takes on average 50% more energy to produce one unit of gross domestic product in the CEE countries than it does in the EU-15. Thus the potential for energy efficiency improvements in the region is huge. EU funds and EIB loans should be used as an incentive to help secure massive energy savings, especially for public buildings, households and the high-rise blocks of flats familiar to most CEE towns, which are notoriously wasteful of heat and in urgent need of refurbishment. At the same time, any EU investments in buildings and industry should be conditional on very high energy efficiency standards.

Source: European Environment Agency, 2007

Energy: investing in a renewable future

EU money can also be used to help unlock the large but unused renewable energy potential of the CEE countries. Not only are biomass, wind and solar energy clean, but they also create more jobs than coal and nuclear power, and spread them across many more communities and regions.

The costs of renewable energy are predicted to continue falling in the future, while the costs of fossil fuels and uranium are set to increase. Those countries that first embraced renewable energy are now the main exporters of the technology and are profiting from the global renewable energy boom (e.g. Denmark in the wind power sector).Investment in renewable energy based on long-term strategies and appropriate environmental and economic criteria is clearly an investment in the future.

Climate-friendly development

Disappointingly, only 2.5% of all EU funding for the 2007-2013 period has been allocated for energy efficiency and renewable energy in the CEE countries. This must be changed so that the opportunity for EU funds to promote a climate-friendly type of development is not missed.

Transport

Road bias in EU and EIB funding

The CEE countries undoubtedly need investment into rehabilitation and modernisation of their transport infrastructure. The question is, however, what kind of infrastructure should be prioritised. The balance chosen will have long-term implications for CEE countries’ greenhouse gas emissions and dependence on oil imports. The EU’s official sustainable development strategy demands reducing the growth of transport, shifting it from road to rail and modernising public transport. Yet the CEE countries are planning to spend twice as much EU funds for roads than for railways in the 2007-2013 period, while funding for public urban transport is set to be marginal. The EIB’s investments have been even more biased in favour of roads in recent years.

Advantages of railways and public transport:

- Railways and public transport consume less energy and emit on average three times less CO2 per passenger-kilometre than cars.

- In the case of freight transport, trains cause five times less CO2 emissions per tonne-kilometre than trucks.

- Buses and trams use 20 times less scarce urban space per passenger than private cars.

- The number of people seriously injured and killed per driven passenger-kilometre is 10-20 times lower for collective transport than for cars.

The one way subsidy street

Disproportionate spending on new motorways has been a constant in transport financing in the CEE region over the last 15 years. As motorway fees cover only a minimal part of their costs, public funds spent on them are in fact subsidising increasing volumes of car and truck traffic. At the same time, public transport and railways have suffered from chronic under-investment, leading to higher fares and a lack of funds for the improvement of services. The result has been a loss of their competitiveness vis-à-vis car and truck transport. It is no surprise that CO2 emissions from the CEE transport sector have surged by 35 percent over the last ten years.

More wealth does not need to mean more cars

Despite all this, the share of freight transported by rail and of passengers transported by public transport is still considerably higher in the new member states than in the old ones. The CEE countries still have a chance to make the right transport choices where Western Europe got it wrong in the past: car dependency, noise and air pollution, urban sprawl and chronic congestion can all be avoided with the help of smart investment of EU funding. Increased wealth does not need to be correlated with increased car dependency. Proof of this can be found in the German city of Freiburg where 60% of all trips are made using public transport, cycling or walking – thanks to careful urban development planning, high-quality service and appropriate pricing.

The need for proper transport strategies and environmental assessments

Reasonable development of transport infrastructure must be based on:

- adequate strategies and assessments of needs to ensure that the most necessary projects are realised; and

- high quality environmental assessments, so that people and the environment do not suffer due to the projects.

Deficiencies are too common

Most of the clashes outlined in this map would not happen if both transport strategies and environmental assessments were carried out correctly. Unfortunately, this is often not the case. In the Czech Republic, for example, transport projects are being built according to outdated plans drawn up more than 30 years ago, even though the government’s own analysis suggests that many of these projects are no longer a priority – a fact repeatedly criticised by the country's Supreme Audit Office. Environmental assessments (SEA procedure for plans and strategies and EIA procedure for individual projects) are often treated only as rubber-stamping exercises rather than important processes for selecting the best possible route and mitigating any negative impacts.

Building infrastructure responsibly

The CEE countries now have an opportunity to modernise their transport infrastructure in an environmentally sensitive and cost-effective way. This chance will be lost if they do not get the transport strategies and environmental assessments right. EU and EIB funding should be given only to those projects where these processes have been carried out properly.

Inland navigation does not require transforming rivers into canals

Inland navigation has an important role to play but should not justify the deepening, straightening and damming of free-flowing rivers:

- The transport function of rivers has to be balanced against all their other benefits and services including the support of valuable ecosystems, flood protection, recreation, fishing, and provision of drinking water, which are all threatened by the transformation of rivers into shipping canals.

- In fact, it is possible to improve navigation on rivers without costly and destructive engineering works - through the technological improvement of ships and more precise water level forecasting. Instead of investing lots of EU money into adapting rivers to deeper and deeper ships, ships should be adapted to rivers.

- Finally, inland navigation will not help reduce the number of trucks on motorways. Water transport usually does not compete with road transport for the same type of freight, while it does compete more directly with rail transport.

Waste

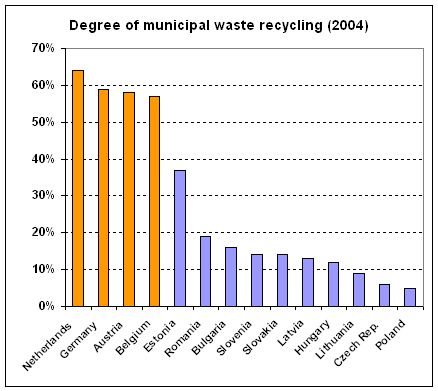

Source: Eurostat 2007

EU funds are an opportunity to improve recycling services…

The average CEE household still produces much less waste than one in Western Europe. At the same time, most CEE countries recycle only 10% or less of their municipal waste, compared with more than 50% in Germany or the Netherlands. The priority for CEE countries in the upcoming years should be to prevent increases in waste volumes, while rapidly increasing recycling. With a focused effort and investment of EU funds, the new member states could develop into recycling societies within a decade.

…but incineration companies are eyeing the money

EU waste policy explicitly promotes prevention and recycling of waste over incineration and landfilling. However, there are pressures to instead divert much of the EU money into promoting waste incineration, which would perpetuate an unsustainable and uneconomic approach to waste for many years to come. In Poland, for example, there is a plan to spend EU funds on nine large municipal waste incinerators at a cost of over €1bn in the 2007-2013 period – this would consume most of Poland’s Cohesion Fund money for waste management. The EU should prevent such misguided investment.

Incinerators – a waste of public money

Incinerators, even if they produce energy by burning waste, are not a good investment of public money because they:

- squander precious materials that could be reused or recycled, thus necessitating imports of increasingly expensive new raw materials from around the world at a huge cost to national economies

- produce high CO2 emissions, thus contradicting efforts to limit climate change

- harm surrounding communities with toxic pollution and generate toxic ash

- will face public protests, leading to difficulties with getting construction permits, thus jeopardising the full absorption of EU funds

- block development of waste prevention and recycling because incinerators require a constant input of large amounts of mixed waste for decades in order to be profitable.

Recycling – better for the economy

- Every tonne of waste that is reused or recycled avoids the extraction, processing and importation of new resources.

- Recycling saves several times more energy than incinerators are able to produce by burning waste.

- Recycling has lower investment and operation costs: a euro spent on recycling services will handle more waste than a euro spent on incineration.

Biodiversity and nature protection

An invaluable gift

The new member states brought an invaluable gift to the EU: large areas of wild or well-preserved nature, and many pristine habitats that are the last of their kind in Europe as well as various animal and plant species that are already extinct in the EU-15. This wealth needs to be treated as a common asset and responsibility. EU funds can and should be used to support stewardship of this natural heritage. It would be a sad paradox if instead they were used to destroy it. Such a loss would be entirely unnecessary.

Natura 2000: what is it?

Natura 2000 is a European network of protected areas selected through scientific assessments as the most important sites for the preservation of rare animal and plant species. The network has been built over the last 25 years and now covers approximately one-fifth of the EU’s territory. The aim of Natura 2000 is to protect and manage vulnerable species and habitats in Europe, irrespective of national or political boundaries. It is also a part of the EU’s commitment to halt the loss of biodiversity by 2010.

Not an obstacle to development

Natura 2000 is however not a system of strict nature reserves where all human activities and new developments are excluded. On the contrary, the sites are intended to be managed in partnership and dialogue with landowners, users and other interest groups. Development projects can be authorised based on certain conditions and steps in order to avoid, minimise or compensate for any negative impacts. However, projects with serious negative impacts on Natura 2000 sites can be approved only in the absence of alternatives.

Conflicts can be avoided

There are dozens of potential clashes between the Natura 2000 network and the planned infrastructure. Fortunately, most of the conflicts can be prevented through better planning and proper environmental assessments. The question is whether there is the political will to do so. This map displays a number of infrastructure projects that seriously clash with Natura 2000 sites only because the possible alternatives have not been examined as they should be.

Kresna gorge may show the way

The case of Kresna gorge in Bulgaria is one of the most serious clashes between a planned motorway and nature. For many years, the project developers and authorities failed to seriously consider alternative routes outside the gorge. Recently, however, thanks among others to interventions by the European Commission, there have been signs of a change in the approach. Alternative routes are now being studied and there is a chance to save this unique area. If Kresna gorge is saved, this may show the way for other conflicting projects.

Contacts

For further enquiries please contact the authors of the map at: billions@foeeurope.org

The following contacts can provide more information about specific projects. Apart from Romania and Slovenia, these are member organisations of CEE Bankwatch Network and/or Friends of the Earth Europe:

Bulgaria: Za Zemiata! (For the Earth!)

Anelia Stefanova (transport projects): anelias@bankwatch.org

Ivaylo Hlebarov (other projects): hlebarov@bankwatch.org

Croatia: Green Action

Marijan Galović: marijan@zelena-akcija.hr

Czech Republic: Hnutí DUHA

Pavel Přibyl: pavel.pribyl@hnutiduha.cz

Estonia: Estonian Green Movement

Peep Mardiste: pepe@ut.ee

Hungary: National Society of Conservationists

Ákos Eger: akos@mtvsz.hu

Latvia: Latvian Green Movement

Alda Ozola: alda@lanet.lv

Lithuania: Atgaja

Linas Vainius: linas@atgaja.lt

Macedonia: Eco-sense

Ana Colovic: ana@bankwatch.org

Poland: Institute of Environmental Economics & Polish Green Network

Ania Dworakowska (IEE: waste projects): anad@bankwatch.org

Robert Cyglicki (PGN: other projects): robertc@bankwatch.org

Romania: WWF Danube Carpathian Programme

Orieta Hulea: ohulea@wwfdcp.ro

Slovakia: Friends of the Earth - Center for Environmental Public Advocacy

Roman Havlíček, havlicek@changenet.sk

Slovenia: Focus Association for Sustainable Development

Lidija Živčič: lidija@focus.si