Case Studies

UK hospital PPPs

Between 1997 and the end of 2010 in England, 102 health sector PPP contracts (or PFI – private finance initiative) were signed compared with just 35 publicly funded health capital investment projects. Another 45 health sector PPP contracts were signed

London Underground PPP

The London underground PPP has been criticised already at an early stage for its high costs and high profits for the private partners. In the end, the PPP was ended when the consortiums were bought by London’s public transport company. In 1998 the UK G

D1 motorway, Phase 1, Slovakia

The controversy about the D1 motorway came from two angles: first, as a PPP its critics said it was overpriced, and second, the project promoter decided not to follow the route recommended through the Environmental Impact Assessment process, instead ch

M25 widening, UK

The M25 widening scheme has faced a barrage of criticism due to its higher than necessary costs and failure to properly assess the alternative option of using the hard shoulder as an extra lane during peak hours. The UK House of Commons Public Accounts

Zagreb Wastewater Treatment Plant (CUPOVZ), Croatia

The EBRD-financed Zagreb Wastewater Treatment Plant, which opened in phases between 2004 and 2007, was intended to improve water quality in the River Sava. No-one disputed that some wastewater treatment was needed in the city, but the project which was

French water concessions

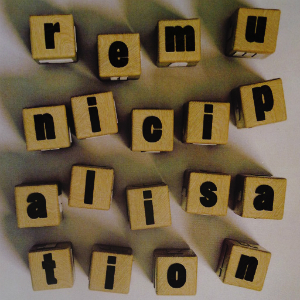

Private water concessions in France have been increasingly challenged, resulting in the re-municipalisation of the water supply in several cities, including Paris. France, as home to the largest water companies globally – Veolia and Suez – is known as

Sofia Water Concession, Bulgaria

In 2000, a 25-year water concession for the Bulgarian capital, Sofia, was awarded to Sofiyska Voda, which was at that time owned by the UK’s United Utilities, and International Water Ltd, in turn owned by Bechtel Enterprises Holdings Inc from the US, a

M1/M15 and M5 motorways, Hungary

Some of the best-known examples of failed PPPs in CEE are the M1/M15 and M5 motorways in Hungary. These were among the rare cases when significant demand risk really was transferred to the private sector concessionaires, but as a result the M1/M15 ende

Croatian motorways: Bina Istra and Zagreb-Macelj

The Bina Istra (Istrian Y motorway) and Zagreb-Macelj (Slovenian border) are the only two motorways constructed using PPPs in Croatia so far, with the Zagreb-Rijeka motorway being constructed by a concessionaire owned entirely by the Croatian governmen

The Palace of Arts, Budapest, Hungary

Budapest had no concert halls of international standards, and primarily due to a lack of state resources it was decided to implement this project as a PPP. Neither prior to nor after the signing of the contract was any impact study (including economic

Arena Zagreb, Croatia

Arena Zagreb is the largest sports hall in Croatia, with a gross area of 90 500 square metres. It was opened in the beginning of 2009, and already in July 2009 the company had accumulated debt of EUR 600 000. To cover the yearly costs of loans, Arena Z

Moscow – St. Petersburg motorway section 15-58 km: A deal involving tax havens and poor value for money

The first section of the Moscow – St. Petersburg motorway is best known for the conflict over its routing through Khimki Forest. The project is widely heralded as being the first public-private partnership (PPP) in the roads sector in Russia. Yet sur

Belgrade incinerator PPP, Belgrade, Serbia

The planned Belgrade waste incinerator, financed by the EBRD, IFC and Austrian Development Bank (OeEB), is incompatible with waste prevention and recycling targets. The European Commission and EIB recognised this, and the EIB therefore refused to finan