A Latvian forest the size of 237 football pitches cut down for an industrial park

by Maksis Apinis, National campaigner, Green Liberty, Latvia

A pristine biodiverse forest in eastern Latvia is being cleared to make way for an industrial park. Even though the project has yet to be approved, half the forest has already been logged to make way for the development. Not only that, the public consultation and social and environmental assessment have been inadequate. The project promoters now expect to get the green light.

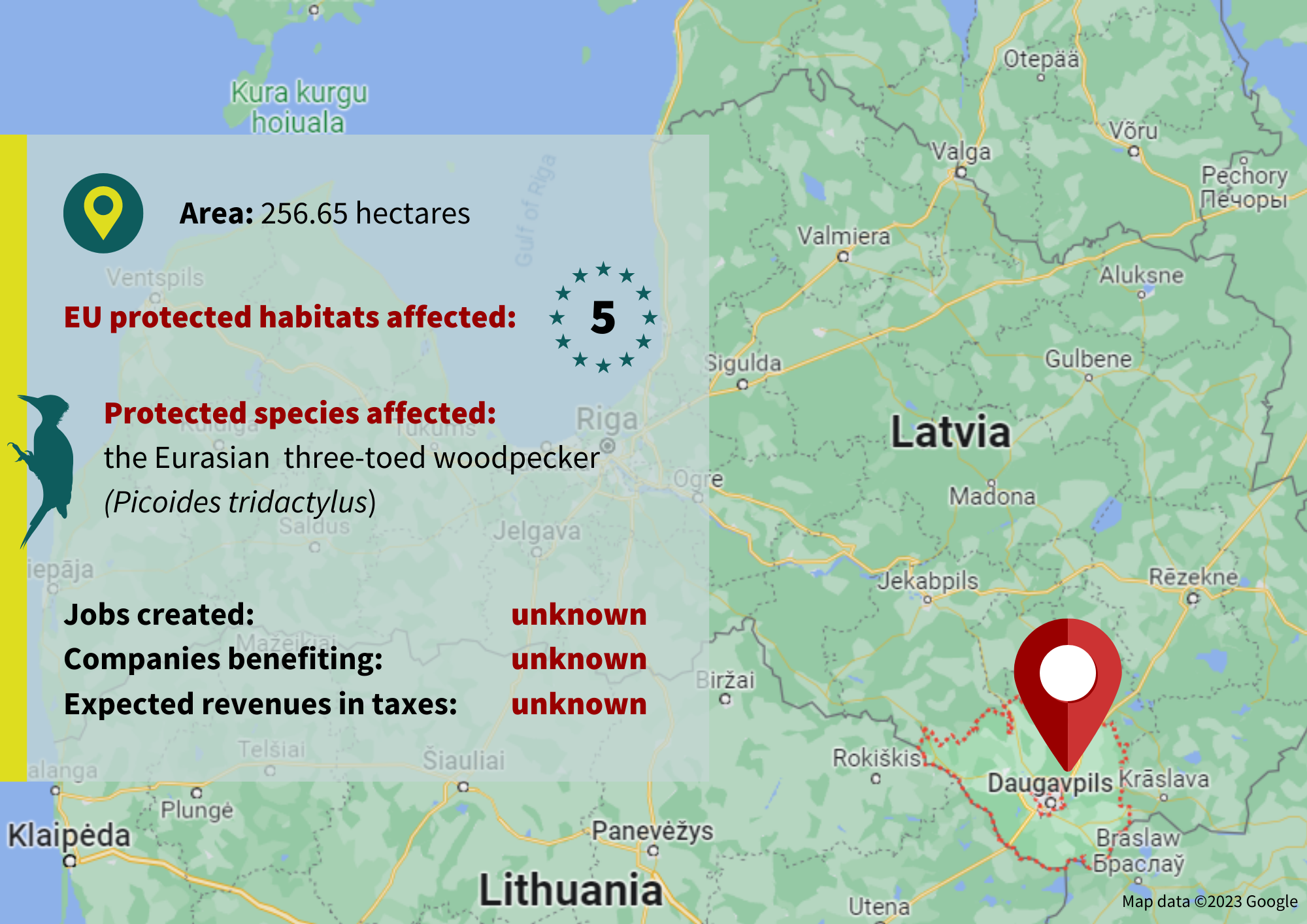

The municipality of Augšdaugava plans to develop an industrial park in the parish of Līksna in eastern Latvia. As part of the project, a 256–hectare forested area, owned by Latvia’s State Forests company, will be transferred to the municipality. The project is set to be financed by a mix of public and private investment as well as EU funds through the cohesion policy or the Recovery and Resilience Facility.

Brazen logging of a biodiverse forest

The municipality states that the establishment of the industrial park is necessary for regional development, and that it will create jobs and tax revenues for the economically struggling municipality. The intended use of the industrial park will facilitate production in the wood processing, transportation, logistics, and energy sectors. The municipality claims that there has been considerable investor interest and that the opportunity should be seized. However, according to unofficial sources, the only expression of interest in investing in this particular site has come from a single Lithuanian investor, who is understood to have rejected other alternative sites.

The proposed site was selected primarily because of its strategic location next to major transport and energy infrastructure. The site is located on both sides of the Daugavpils bypass road to Riga and in close proximity to the Indra–Daugavpils–Krustpils–Riga railway line. It also benefits from being close to high-voltage power lines (110–330 kilovolts) and a distribution substation.

However, given the project’s intended activity profile, there is no clear justification as to why such a vast area was deemed necessary for the site. Although not so ideally located from an infrastructure point of view, several alternative degraded and brownfield sites in the municipality, each of which is smaller (up to 50 hectares) than the proposed site, have been overlooked.

In July 2022, Latvia’s Nature Conservation Agency recommended that a strategic environmental assessment (SEA) be carried out. The decision was taken on the grounds that the proposed site borders a Natura 2000 reserve and encompasses a biodiverse forest, home to EU-protected habitats and endangered species, including the Eurasian three-toed woodpecker.

The SEA for the project was released by the municipality shortly before a final parliamentary vote on a law setting out the rules for transferring the ownership of the site to the municipality. This coincided with the commencement of public consultations on amendments to the regional territorial plan. However, the manner in which the assessment was conducted has raised concerns.

Firstly, the assessment carried out by the habitat experts covered the condition of the forest only after the significant logging had taken place, which means that the extensive damage caused by the logging carried out in anticipation of the project was not assessed. Secondly, the SEA assumes that some of the felled areas may be reforested at some future point and that unaffected areas may be preserved as forest. However, this is highly unlikely given that the entire site is earmarked for industrial use.

Undemocratic land expropriation

For the industrial park to be developed on the site, state-owned forest land must first be expropriated to Augšdaugava Municipality. However, Latvia’s Forest Law dictates that state forest land can be expropriated only in very specific cases, one of which is the development of an industrial park. This scenario also requires a dedicated law to be passed. The Forest Law also stipulates that in order for state forest land to be expropriated in such a case, the development plans for the industrial park must be reflected in a municipal development programme. Additionally, an evaluation of alternative sites must be carried out, demonstrating that they are not available in the municipality or region concerned. To date, none of these conditions have been met.

Despite this lack of compliance, on 15 November the Latvian Parliament approved a new law that sets out the rules for transferring the state forest land to the municipality. Regrettably, proceedings thus far have flouted good management practice. For instance, the decision to expropriate the forest land was made without following prior statutory procedures, such as formulating a local development plan, organising public consultations or developing an SEA.

Although the law does include a requirement to return ownership of the land to the state under certain conditions, such as if environmental protection legislation prohibits the development of the industrial park on the site, the project promoters expect, based on their statements to date, that the outcome of the public consultation and SEA will favour the project and have no effect on the decisions already taken.

The inclusion of the land return condition was strongly recommended by the Parliament’s legal department, which had previously called for the draft law to be postponed until the SEA was completed, citing non-compliance with legal provisions, including the absence of an assessment of alternative sites. However, on 7 November during a meeting of the Parliament’s economic policy committee, when members of parliament agreed to submit the law for a third and final reading, the deputy head of Augšdaugava Municipality, Vitālijs Aizbalts, expressed confidence that the article would not be invoked and that the land would never be returned.

The fact that this law was adopted before the necessary legal procedures and documents had been approved may also have set a dangerous legal precedent, one that encourages other local authorities to adopt undemocratic practices when developing similar projects. Statutory procedures are essential to protect the public interest and should not be seen as unnecessary red tape.

Violation of the ‘do no significant harm’ principle

On 20 June 2023, at a meeting of the Parliament’s economic policy committee, where it was decided to submit the bill to Parliament for a second reading, Aizbalts revealed that Latvia’s State Forests company had already felled significant proportion of the trees on the site in preparation for the implementation of the project. Regrettably, approximately 50 per cent of the forest has already been logged to make way for the development.

The clear connection between the logging carried out by Latvia’s State Forests company and the industrial park project is an essential consideration in any evaluation of a project’s compliance with the principle of ‘do no significant harm’. If a pristine forest has been cleared to make way for an industrial park, endangering protected habitats and ignoring viable alternative sites in the process, then it is clear that this principle has been violated. Under no circumstances should EU public funds be allocated to such a project.

Latvia faces a major challenge in achieving its goals of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, especially in transforming the role of the land use, land-use change and forestry sector from carbon emitter to carbon sink. In this context, it is simply unacceptable that such a vast area of forest land is being culled without an in-depth analysis or feasibility study.

Plans for the industrial zone also involve the installation of wind turbines and a solar energy park. While there are plans to develop wind farms in other forested areas in Latvia, hacking down a forest containing habitats with an unfavourable-to-poor protection status in order to build a solar panel park and wind turbines is unjustifiable from a biodiversity and climate point of view, and certainly casts a shadow on the overall sustainability of renewable energy incentives.

There is no doubt that investing in the promotion of climate-neutral industries and green jobs is necessary to ensure Latvia’s geographically balanced development and a just transition in the affected regions. However, this should not be achieved at the expense of biodiversity and climate goals, or by supporting developments that are detrimental to these values.

Ilze Mežniece, a local resident from from Augšdaugava region said,

‘Local residents noticed that the forest was being logged, and heard that the industrial park will be developed there, but nothing was clear. No one explained anything. The way the project is proceeding is unacceptable. The municipality doesn’t respect formal procedures and rules. It is still unclear why such a vast area is needed for the activities they plan to have there.’

Alternative viable sites in Augšdaugava, already degraded and available for industrial use, have not been sufficiently explored. The way in which this project has been rushed through is deeply worrying and reinforces the misconception that a project can be carried out on a dubious legal basis without giving the public a chance to have their say.