The Oder River, which forms the border between Poland, Germany, and the Czech Republic, faced a severe environmental disaster in 2022. More than one year later, the river is in peril again. The decisions taken by the previous government have so far only exacerbated the situation. Now, a new government offers one last opportunity to show environmental stewardship and reverse the catastrophe.

Rafał Rykowski, Biodiversity campaigner, Polish Green Network | 1 December 2023

Jacek Engel, Fundacja Greenmind

The dark summer of 2022

One year ago, toxic golden algae eradicated over 200 million fish, mussels and other river life in the lower section of one of the most precious rivers in Europe. Intriguingly, these algae are typically found in saline environments and were able to thrive in the freshwater only because of the high level of pollution in the river.

According to the newest report’s estimations (a report prepared by independent experts and scientists from different organisations and published in the Science of The Total Environment), well over half of the fish population in the Oder was killed in this horrific catastrophe. Some protected species, like the spined loach and the European bitterling, were virtually eradicated. Only 3 per cent of their populations survived.

The population of the duck mussel, a native species of mussel that is an excellent filterer of river water, has been severely affected by the disaster. Without it, the Oder will find it even harder to cope with the existing pollution. Experts have estimated that as much as 95 per cent of the population of this bivalve mollusc has died in the lower Oder. This species will likely be replaced by an invasive species, the Chinese pond mussel, which has proven to be more resilient to the effects of the disaster. This is a harbinger of doom to the aforementioned European bitterling, listed in Annex II of the Habitats Directive. The reproduction of the fish is closely related to the presence of mussels in the river. Females lay eggs in the gill cavities of the mussel, and both the fertilisation of the eggs and the development of the larvae take place inside of it.

The above is just one example of how the river’s biodiversity has been seriously jeopardised. Moreover, it is estimated that at least 147 million aquatic snails have been found dead on land – indicating a population decline of 85 per cent. As we read in the study results, these invertebrates are an essential food source for other organisms and play a key role in nutrient cycling and decomposition.

However, the toxic prymnesin produced by the algae was only a murder weapon, not the culprit. That bio-crime was man-made. The algae that thrive in brackish water would not have proliferated so much if not for the pollution in the river. Salty mine wastewater is discharged into the Oder. A Greenpeace report and other researchers prove this beyond any doubt. Discharges are often done lawfully, in broad daylight. Sometimes, though, they are also done covertly, with waste flowing secretly from pipes hidden in the bushes. The high salinity (for which not only mines but also industrial plants discharging into the Oder are responsible), the hot summer, high water temperatures, and low flows created the ideal conditions for a disaster of this magnitude. Such a catastrophe and so much loss of life in the river have never been documented before in this part of Europe.

One year later: death by neglect

The high salinity levels of the Oder River have persisted. The golden algae is still there. In recent months, the river water in some places has had twice the level of salinity as the Baltic Sea. However, by sheer luck, a repetition of the full-scale disaster was avoided this year, but not without many local calamities. In October, the operation of the thermal power plant in Szczecin was suspended due to the salinity of the water. The conductivity of the Oder River in Szczecin had been exceeded for many weeks, and the plant’s water filters could not cope.

Although the outgoing government presented a report in March of 2023 in which it stated that ‘the transformation of the Oder riverbed and its long-standing pollution had led to the decline or extinction of [protected mollusc species]’ and confirmed the golden algae claim, it took no concrete action to avoid a similar disaster in the future. Not only that, but the Minister of the Environment, Anna Moskwa, seemed to disregard the salinity of the river water, arguing that, after all, life thrives in salt water, too. The mining and heavy industry also shrugs off responsibility for the disaster, arguing that it discharges wastewater into the river legally and in an environmentally safe manner. Unfortunately, the reality is that permits for discharging sewage into the Oder are plentiful, and the limits are high.

What are the politicians doing in light of this gloomy situation? Instead of increasing the river’s resilience to similar events in the future, they are taking actions that weaken the river.

The Oder River Special Act: the final nail in the coffin?

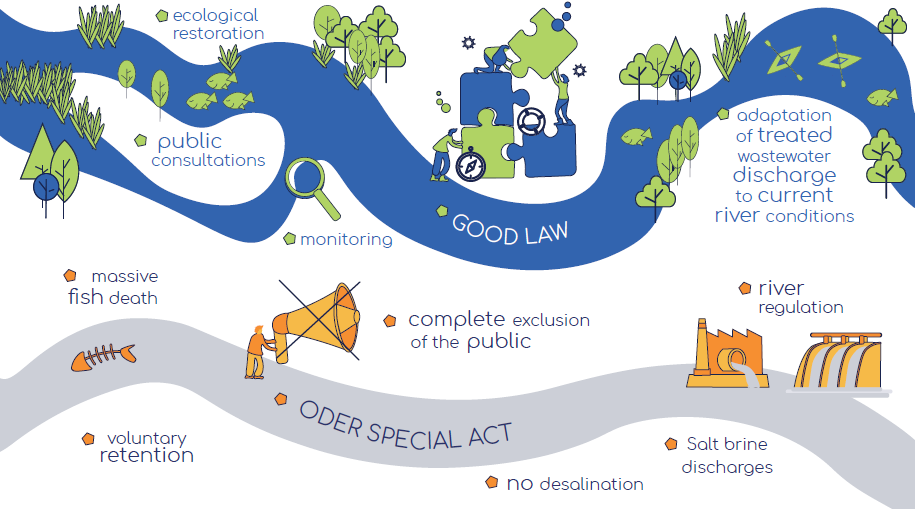

Environmental organisations proposed solutions for restoring the river very quickly after the disaster. In the White Book of Polish Rivers, non-governmental organisations analysed the legal incoherences and harmful policies that led the Oder River ecosystem to collapse and recommended the changes in water management that were needed to ensure real river protection. These included stopping the construction or reconstruction of regulatory structures (such as dams, barrages, weirs, and groynes), improving monitoring, starting restoration, and implementing solutions to minimise run-off and saline water discharges from industry plants and mine shafts.

The government decided to respond and, shortly before the October elections, pushed the Oder River Special Act through the Parliament. It could have been an excellent opportunity to rectify bad policy and restore the river. Unfortunately, though, this legislation is incompatible with the Water Framework Directive, and to make the situation even more troublesome, it goes against the government’s recommendations in its own report on the disaster. According to expert analysis, the proposed solutions would neither contribute to the restoration of the river and the natural environment, nor would they improve flood safety or combat the effects of drought.

‘The Oder River Special Act contains some 160 hydro infrastructure investments destroying the Oder and its tributaries, the implementation of which will exacerbate the water crisis. It does not provide any restoration measures to strengthen the Oder’s pollution resistance or self-purification capacity. This is a death sentence for this river.’, says Majka Wiśniewska from Greenmind Foundation (a member of the Save the Rivers Coalition and the coalition Time for the Oder), one of the organisations that prepared the analysis.

As if that wasn’t enough, the most bizarre provision of the Oder act is the creation of a Water Inspectorate, a new monitoring institution. Establishing a new institution will only exacerbate the already considerable chaos in water management in Poland. According to the law, the Water Inspectorate will be able to use direct coercive measures, and inspectors will carry guns, batons and gas. The new ‘water police’, armed and with unclear competencies and jurisdiction, are probably the last thing the suffering Oder needs right now.

According to Krzysztof Smolnicki from the Foundation for Sustainable Development (a Save the Rivers Coalition and Time for the Oder member), ‘The Oder Special Act is economically and socially harmful to nature. It poses a threat to the unique natural values of the Oder valley. It imposes unreasonable costs under the dubious pretexts of flood protection and combating pollution. As a law which has not been the subject of a broader public debate, it takes no account of the public interest.’

The Oder act avoids the main problem – the river’s high salinity level caused by pollution – by a wide margin. Instead, the bill contains harmful investments like weirs, water steps, and other river regulations. Salt discharge fees have remained low, not motivating mines and industrial plants to implement desalination systems. The important polluter pays principle does not apply under this law. Instead, the legislator gives priority to retention and dosing systems. The reduction of the fee for entities retaining brine for five days, as mentioned in the law, is actually a reward for discharging salt into the Oder.

New elections bring new hope: what can the new government do?

So what should be done? First and foremost, the protective umbrella for plants discharging salt into rivers should end. Charging mines for water from mine dewatering, setting upper limits for chloride and sulphate concentrations in the wastewater released by these facilities, increasing fees for salt discharges, and relief for entities able to halt brine discharge for a minimum of 30 days are the most important recommendations of the legal analysis prepared by the Frank Bold and Greenmind foundations for the Save the Rivers Coalition. The experts also propose a meticulous study of cumulative impacts before issuing water permits for discharging wastewater to rivers.

‘The cost of eliminating the threat of saline rivers probably shouldn’t be placed solely on the mining industry. Access to clean water is the responsibility of the whole state. Therefore, the possibility of implementing financial mechanisms to support mines in solving the problem of saline water should be considered, just as industrial plants and local governments are supported in building sewage treatment plants’, emphasises Jacek Engel of the Greenmind Foundation.

The amendment of the Oder River Special Act should be on the list of priorities for the new government. Without the solutions mentioned above, this law, based on pouring more tonnes of concrete into rivers, regulation, and establishing the absurd water police is pointless and harmful.

‘We expect the new government to urgently bring about the novelisation of the Oder River Special Act and, above all, to work immediately on a law that will reduce the river salinisation problem generated by industry and mines’, says Majka Wiśniewska.

This expectation is underpinned by the coalition agreement signed by parties that have so far been in opposition, but their electoral result indicates that they will create a new government. In the agreement, the parties write about ‘implementing permanent monitoring of rivers and pursuing river restoration’ and a ‘programme for the restoration of marshes and peatlands’. Some of the money needed to pursue that goal will be found in EU funds, including the – hopefully soon to be unlocked for Poland – Recovery and Resilience Facility funds, although the allocation for biodiversity included there should be significantly higher. The problematic question may be whether or not everyone in the broad party coalition understands ecological restoration and solutions supporting nature in the same way.

A change of government is a political opportunity to stop the fragmentation of Poland’s rivers and to stop flooding them with concrete. It is high time that taxpayers’ money was finally channelled into protecting waters and restoring their ecological health. This will benefit us all, and our rivers will finally breathe a sigh of relief.

Never miss an update

We expose the risks of international public finance and bring critical updates from the ground – straight to your inbox.