In the current age of ‘competent white men’, ‘traditional family values’ and the EU’s simplified sustainable finance regulations, what lies in store for the inclusion and equality policies of Europe’s public development banks?

Fidanka Bacheva-McGrath, Strategic Area Leader, Cities for People | 7 March 2025

At the annual EIB Forum in Luxembourg this week, Nadia Calvino, president of the European Investment Bank (EIB), called for a renewed determination to ‘shape a future where gender equality is not just an ambition, but a reality’. Two forum sessions dedicated to gender delivered the following resounding message to capital markets and EIB partners:

Women’s economic inclusion and diversity are not just a matter of fairness but an economic imperative.

These signals are particularly timely given Brussels’ looming deregulation agenda and conservative political elites framing misogynistic rhetoric and hate speech as freedom of expression. Amid major shifts in the global political order, economic alliances, and normative values, gender action is likely to be caught in the crossfire between old and new priorities as they compete for EU spending and international development finance.

This is why President Calvino’s leadership at the EIB Forum is so significant. Her message that inclusion is not just the right thing to do, but also the smart choice presents a strong business case for gender equality and its role in building peace, stability and shared prosperity.

Easier said than done

UN Women have identified public development banks as key drivers of gender equality. Indeed, many international financial institutions have committed to promoting economic inclusion and women’s empowerment as core business objectives.

For example, economic inclusion is set to become one of the three pillars of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s (EBRD) new Strategic Capital Framework, expected to be approved by the bank’s shareholders at the EBRD annual meeting in May – which will guide EBRD investments over the 2026–2030 period. Additionally, the EBRD’s new safeguards policy includes new commitments and project requirements for promoting diversity and preventing discrimination, gender-based violence, sexual abuse and exploitation. EIB’s environmental and social sustainability framework from 2021 sets similarly strong standards.

But policies are only as effective as their implementation, and ‘gender-smart’ projects often look much better on paper than they do in reality. For instance, while a recent assessment by the EBRD’s independent evaluation department found that EBRD investments receive a gender-smart tag for setting ambitious gender goals and introducing relevant activities at the project approval stage, the evaluation also concluded that gender promises are not always upheld during project implementation.

Part of the problem is the lack of ongoing support and monitoring by bank teams, resulting in patchy implementation. Notably, the EBRD’s dedicated and highly committed gender and inclusion team does not have enough capacity to support all tagged projects. That’s why public development banks must back up their commitments with real action. To successfully implement gender objectives, projects require sufficient dedicated resources to make a tangible difference when it comes to equality, diversity, and the protection of women’s rights.

The common practice of blending loans with technical assistance grants from donors is an effective way of strengthening the capacity of borrowers to achieve these objectives. In their capacity as bank shareholders, donors should also provide additional resources and establish adequate mechanisms to ensure grants are strategically targeted and effectively disbursed, creating an enabling environment for gender-smart projects.

Policy dialogue at country and sectoral levels, as well as greater transparency and stakeholder engagement are part and parcel of that enabling environment. Public banks often support policy and planning processes at national and local levels through trade facilitation, tourism development, digitalisation of rural areas, the just transition of mining regions, sustainable urban mobility, and climate adaptation in the water sector.

But these plans must go beyond simply incorporating gender considerations – they must also be transparent and participatory, designed for women and with women. This means not just initiatives led by ‘women in business’ or for ‘women entrepreneurs’, but inclusive efforts that directly involve women impacted by intersectional vulnerability and discrimination. Only then can gender programmes and products truly reach and empower those who need them most.

Not all strategies are made equal

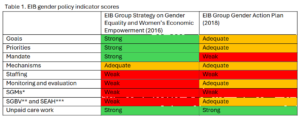

Civil society scoring of the environmental and social frameworks of 12 public banks ranked the EBRD’s and EIB’s policies as the strongest. Looking more closely, however, the EIB’s 2016 gender strategy is outdated and lags behind those of its peers, such as the EBRD. While the EIB published its first Gender Action Plan for 2018–2019, the second plan for 2021–2024 has not been published. Bankwatch requested access to the second plan but received only a heavily redacted version of the document. While the EIB prepares its own evaluation of the implementation of its strategy and action plans, civil society scoring has already highlighted key areas where the EIB’s gender strategy could improve.

* SGMs – sexual and gender minorities

** SGBV – sexual gender-based violence

*** SEAH – sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment

Acceleration based on impact strategy and ambitious targets

To turn President Calvino’s call at the EIB Forum into concrete action, the EIB and its shareholders must update the bank’s gender impact strategy and set more ambitious goals for gender equality and women’s economic empowerment.

First, the EIB’s new gender strategy should widen its scope and aim for at least 50 per cent of the EIB’s portfolio to include gender-smart objectives and activities. President Calvino stated at the EIB Forum yesterday that to accelerate action, a target of at least 40 per cent is needed. Moreover, rising to this challenge will require dedicated resources, internal capacity-building, and a system of incentives, as well as operational tools to support borrowers and enhance policy dialogue. For example, the Joint Assistance to Support Projects in European Regions (JASPERS) partnership, funded by the EIB and the European Commission, can play a key role in this process.

Second, the EU’s house-bank strategy must incorporate much wider and more detailed gender equality and diversity objectives, aligning them with the high standards of its environmental and social framework. This should include, for example, objectives for assessing gender gaps, preventing discrimination, and addressing gender-based violence and harassment among borrowers’ workforces, infrastructure and service users, and communities affected by EIB investments.

Finally, both the EIB and the EBRD must set clear standards, and provide borrowers with guidance notes, on incorporating the principles of economic inclusion and gender equality into projects complicated by conflict, war and crisis. Women’s rights and gender quality must guide the banks’ efforts to make fragile societies more resilient, ensuring the protection of vulnerable groups and unlocking the potential of women’s economic empowerment.

Never miss an update

We expose the risks of international public finance and bring critical updates from the ground – straight to your inbox.