Energy efficiency is taking centre stage in the Energy Union. Last summer, after long negotiations between the Parliament and the Council, a new energy efficiency target was set at 32.5 per cent by 2030. To meet the target, Romania is channelling public funds into renovating its residential sector which accounts for as much as 86 per cent of the country’s built environment.

Laura Nazare, National campaigner in Romania | 4 June 2019

In Romania, the potential for energy efficiency improvements in buildings is vast. Most residential buildings from the second half of the twentieth century lack specific thermal requirements for the envelope, which leaves a lot of room for improvement.

Investing in thermal rehabilitation

Since the early 2000s, legislative frameworks and different funding opportunities have helped spur thermal rehabilitation works in the housing stock.

In Bucharest, the rehabilitation works were carried out through these programmes:

- 2009: the National Programme for Energy Performance Improvement of Apartment Buildings

- 2010-2016: the Thermal Rehabilitation Programme for Apartment Blocks financed by government guaranteed bank loans

- 2012: a government ordinance enabling local administrations to finance local budgets designated for increasing energy performance of housing blocks or single-family houses.

Through the national programme for energy performance improvements for housing blocks the Ministry approves local budget allowances for municipalities, towns and communes, and Bucharest districts, based on local programmes and funds allocated from the state budget.

The other programme financed through government-guaranteed loans facilitates access by homeowners’ associations to contract bank credits with subsidised interest rates for thermal rehabilitation.

According to the District 3 city hall, since 2012, 922 apartment blocks were thermally rehabilitated through the local programme. The Court of Auditors report states that in the 2010-2014 EU Budget period, a total of 2 248 housing blocks were rehabilitated, or 28 per cent of the blocks in Bucharest.

How it works

- Housing blocks are identified and owners’ associations are notified about registration in the programmes.

- If an owners’ association decides to register, a decision of the general meeting of the owners is required to sign a mandate contract. This contract mandates local authorities to carry out intervention works and sets out other relevant obligations and clauses.

- The design and execution of intervention works start.

- At the final reception, an energy performance certificate is issued together with a three-year performance guarantee period.

What seems like a simple procedure may actually stretch over a long period of time: not all owners in the association might agree on the works, administrative bottlenecks might obstruct the process, contracting processes sometimes get stuck.

One community’s experience

The administrator of one of Bucharest’s owners’ associations detailed his experience with the local thermal rehabilitation process. The apartment block he manages is 22 years old, and since its construction there has not been any other rehabilitation works.

He explained: “Things ran smoothly with those in charge at the city hall. Although they initially said that the association would bear 20 per cent of the total costs, till now, two years after the intervention works have finished, the administration has not charged us anything.”

In practice the owners’ association pays 20 per cent of the total cost of the rehabilitation works and the remaining 80 per cent is provided by the state through local budgets. This 20 per cent is shared among all owners according to their individual share of ownership, but if an association or one or more owners cannot pay their share, the local city hall may partially or fully take over the costs and decide later how to recover the money.

The design of the intervention works is where issues begin to arise. He complained, “The design is done in the office and nobody comes to see the situation on the site. Everything is based on pictures and even if unforeseen situations occur during work, they still send someone to take a picture and send it back to the design office.”

Overall, the association was satisfied with the work done: “They changed the buildings’ envelope, all the hot water pipes in the basement, and now the pipes are all new, insulated, and from this point of view it is good because those were about 20 years old. They also insulated the roof and they did it quite well, as we never have leaks.”

The authorities, however, never conducted the final reception. Legally this means that the energy performance certificate of the building was not issued, which would have highlighted the specifics of annual energy consumption for heating. But according to the owners “it is indeed warmer than it used to be and heating bills have also fallen.”

In 2014, media reported a case where an apartment block rehabilitated in 2010 was approved to undergo the same rehabilitation works four years later. Of course these works never started because they were already done, but this did not stop the city hall from expensing the funds anyway. This unresolved case highlights the need for more transparency in the work of local authorities.

Who is footing the bill?

These large-scale programmes require massive injections from the state budget. Across some districts of Bucharest, the local administration also contracted the European Investment Bank loans for additional funding.

EIB Thermal Bucharest projects in Romania 2009 – 2018

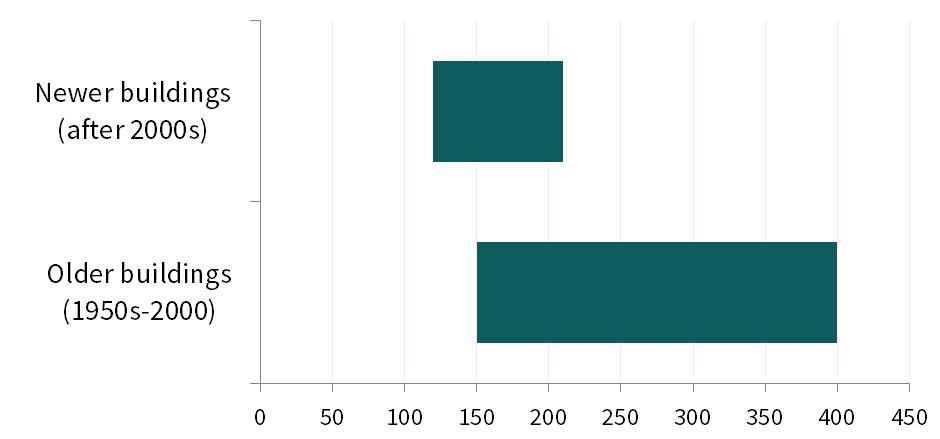

The share of loans in thermal rehabilitation payments, 2010-2014 (Court of Auditors’ report)

The loans represent an important source of financing for local programmes, but they also significantly increase the rehabilitation expenses borne by the local budget, the report concludes. These credits are contracted in a foreign currency, with a floating rate, meaning there are bigger risks that they cannot be repaid in the event of unfavourable developments in the exchange rate.

European funding is also available through Priority Axis 5 of the Regional Operational Programme 2014-2020 which supports the increase of energy efficiency for public and residential buildings. According to the Ministry for Regional Development and Public Administration, District 3 received from the Regional Operational Programme 2014-2020 EUR 11 million and District 4 received almost EUR 16 million.

Way forward

Between 2009 and 2018, the EIB financed EUR 605 million worth of energy efficiency projects. Although such investments carry some risks, the EU bank should continue deploying investments in the energy efficiency sector, instead of supporting uneconomic, unsustainable fossil fuel projects. To minimise currency fluctuation risks, the EIB should preferably provide loans in the local currency. A transparent system of the apartment owners’ contribution should also increase the efficiency of public funds use. The program should aim at complex and high quality energy efficiency measures works which should be monitored and confirmed by a certificate of energy performance.

With a wide range of financing sources available, these energy efficiency interventions for residential buildings could be carried out in a simpler, more transparent manner. Instances where a contracting process of rehabilitation works is obstructed by dubious mechanisms of public procurement or administrative delays must not become a habit, because authorities have all the means for making thermal rehabilitation a success.

Never miss an update

We expose the risks of international public finance and bring critical updates from the ground – straight to your inbox.

Institution: EIB | EU funds

Location: Romania

Project: District heating | EBRD/EIB energy policy review

Tags: Energy Union | energy efficiency