District heating

Winters have become a stark reminder that we need to speed up the energy transition. In central and eastern Europe and the Western Balkans, district and individual heating are still dominated by polluting, expensive fossil fuels and other unsustainable energy sources. Europeans deserve warm homes without having to fear exorbitant energy bills, chronic air pollution or an out-of-control climate crisis. More national and local governments need to utilise European public finance to tap the massive potential of various renewable energies to power district heating systems so we heat homes, not the planet.

Stay informed

We closely follow international public finance and bring critical updates from the ground.

Key facts

Heating and cooling accounts for almost half of the EU’s energy consumption. Yet according to Eurostat data, in 2021 renewables made up just 23 per cent of heating and cooling consumption in the EU.

Similarly, in the Western Balkans indoor heating and hot water supply continue to rely predominantly on fossil fuels. According to the Energy Community Secretariat, fossil gas and coal accounts for 97 per cent of the energy produced for district heating. Renewable energy sources are a meagre 3.5 per cent including biomass. Investments in energy efficiency in the region remain insufficient while only around 14 per cent of the total regional heat demand is produced and distributed to final users in district heating systems.

The predominant heating systems are anything but sustainable. In addition to massive dependency on polluting, and increasingly unaffordable, fossil fuels, existing district heating systems are often characterised by outdated and leaky pipelines, and distribution networks that serve buildings with poor energy efficiency performance.

Key issues

Transforming the way European homes are heated is crucial for tackling the climate crisis. To meet the EU’s goal of cutting 55 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions and increasing the share of renewables in final energy consumption to 40 per cent by 2030, governments in central and eastern Europe as well as in the Western Balkans have to urgently speed up the roll out of renewables-powered district heating systems. Even more concretely, the adoption of the EU’s new Renewable Energy Directive (RED III) means governments in central and eastern Europe need to increase the share of renewable energy sources in the heating and cooling sector by 1.3 percentage points every year between 2020 and 2030. The Energy Efficiency Directive defines ‘efficient district heating systems’ as those using at least 50 per cent renewable energy, 50 per cent waste heat, 75 per cent cogenerated heat, or 50 per cent a combination of such energy and heat.

EU public finance can play a decisive role in the process. In particular, multilateral development banks such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the European Investment Bank (EIB) must avoid any financial support to fossil-fuels-based heating and instead direct investments toward renewables-powered heating systems, the modernisation of heating grids, and renovation and insulation.

Background

The recent energy crisis and worsening climate disasters in Europe and around the world are reminders that we have no time to waste.

The energy transition is well underway, but it needs to be accelerated. In fact, district heating systems based on renewable energy sources are already a reality in numerous municipalities across Europe and beyond, and as part of the just energy transition they must be made the standard.

The towns that turned to sustainable district heating before it was cool

Shifting municipal heating networks to run on renewables might seem like a daunting task. But there is no need to reinvent the wheel. Communities throughout Europe which made this important decision some years ago now have become inspiring sustainable district heating success stories.

In Denmark and in Austria, several municipalities have already chosen to decarbonise their district heating systems by investing in innovative technologies that are based on renewables – from solar thermal in Dronninglund to a large-scale heat pump in Vienna. Read more here.

Geothermal energy is already proven as a sustainable source for district heating, as multiple communities throughout Hungary and Slovakia can testify. Read more here.

Communities from the Baltics to the Balkans deserve affordable, clean and reliable heating. Regions in central and eastern Europe and the Western Balkans that are transitioning away from coal should avoid switching their district heating systems to fossil gas and rather power them with renewables. (See here for a more detailed look at what such systems can look like.) District heating systems powered by solar, wind or geothermal energy are no science fiction. And, in fact, study after study shows that many towns and cities have a huge potential to develop renewables-powered district heating systems.

Western Balkans

Report: Heating in the Western Balkans. Overview and recommendations for clean solutions

Study: Analysis of alternatives to coal-based district heating for the Bitola region in North Macedonia

Study: Analysis of Sustainable Heating Options for the City of Tuzla, Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Study: Identification and analysis of potential sustainable heating solutions in Pljevlja, Montenegro

Central and eastern Europe

Shifting from fossil fuels to sustainable district heating – the view from Hungary and Latvia

Public investments can play a decisive role. First, no public money should go into heating systems based on fossil fuels. Instead, EU funds and multilateral development banks need to urgently mobilise their resources and direct more investments to municipalities to introduce or expand sustainable district heating systems based on renewable energy sources.

Briefing: How can the EIB and the EU financial mechanisms support the decarbonisation of district heating?

Watch city officials from communities in the Western Balkans discuss the development of sustainable district heating

Coal

Nearly half of the coal heat supply in Europe is burned in household coal stoves, which are almost exclusively located in Poland. Not only do these cause significant CO2 emissions, but the largely unfiltered exhaust gasses also lead to serious air pollution, which causes severe health problems and premature deaths.

The other half of coal-derived heat is generated in combined heat and power (CHP) plants and, to a smaller extent, in heat-only boilers. These facilities supply mostly urban district heating grids and are primarily located in Poland, Germany and the Czech Republic. More installations can be found in northern Europe (Denmark, Finland), eastern Europe (Slovakia) and southeast Europe (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Greece, Romania). In the Western Balkan countries, in particular Montenegro, there are projects to connect existing conventional coal power plants to district heating systems.

When considering cleaner alternatives to transform the heating sectors, decision makers mostly opt for gas or biomass, and for CHP technology. None of these are truly sustainable heating solutions.

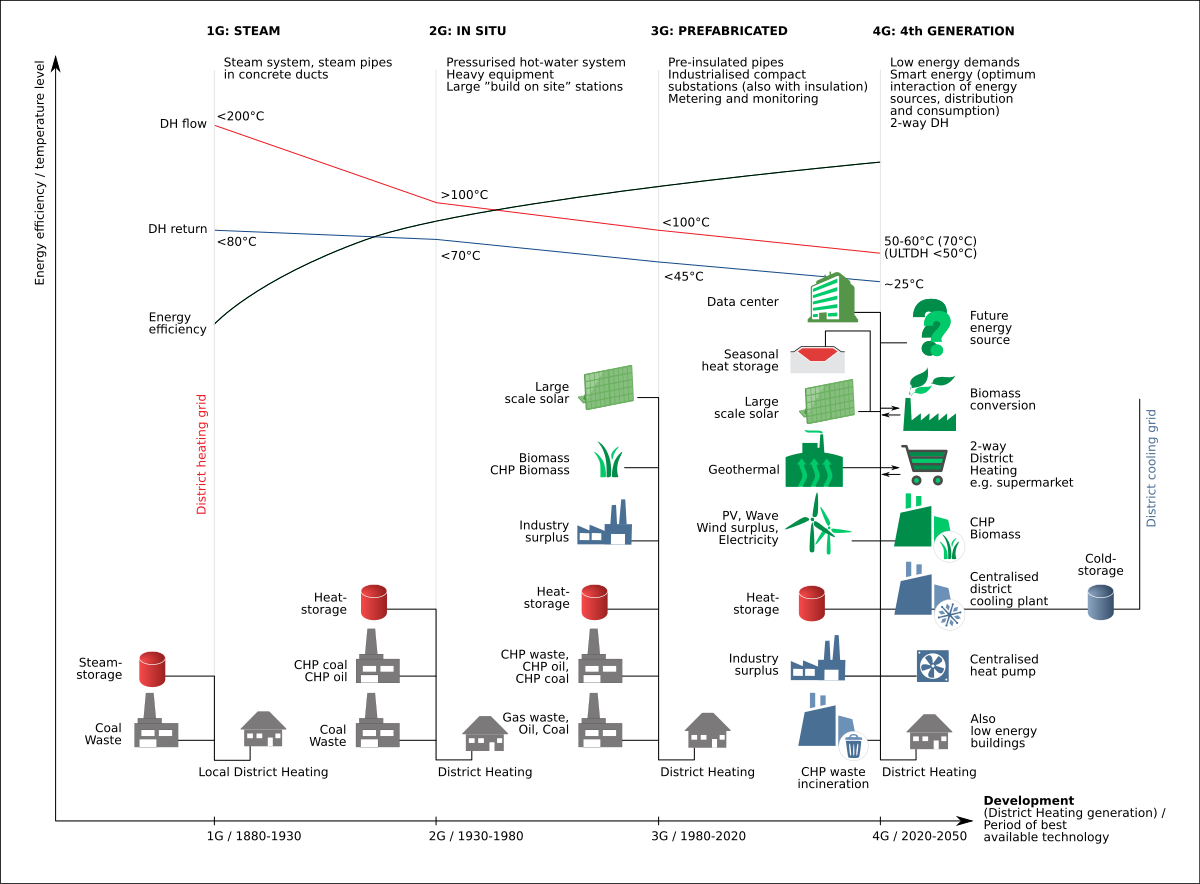

Many district heating systems in the CEE region were built around the 1980s. They are mostly second generation systems running on high temperatures above 100° C. In locations like the Western Balkans, district heating is only used for space heating. The old heating networks suffer from poor insulation of pipelines and high losses of heat and water leakage. On the demand side, deep renovations of the existing building stock are lacking, and people often have little or no control over the heat consumption in their homes.

Fossil gas

Gas is a fossil fuel with significant carbon intensity – when counting methane leaks during extraction and transportation, fossil gas is no better than coal.

In some parts of Europe, like in the Western Balkans, gas has not traditionally been used much. Albania, Kosovo and Montenegro have no access or limited access to fossil gas at present. Pushing for gas means investing in hugely expensive infrastructure to be built, in some cases from scratch, along the entire demand chain. Any fossil gas infrastructure built today faces the risk of becoming a stranded asset. Alternatively, such installations could cement demand for fossil fuels for decades and risk locking these countries into fossil fuel dependency, as well as an import dependency. The lifetime expectancy of these projects is at least 30 years, and on top of that there are usual delays in planning and construction (on average 5 to 10 years at the EU level). This would delay the transition to a zero-carbon economy, because investing in fossil gas slows the uptake of renewables.

There is also a growing trend of promoting hydrogen as a cleaner source. However, almost all hydrogen is currently made using fossil fuels, and even renewable hydrogen is pointless to use for heating as it is energy intensive compared to using renewable electricity directly – some estimates find that the amount of green electricity needed to produce green hydrogen is 500 to 600 per cent greater than what is needed for the equivalent number of heat pumps.

Biomass

Biomass is not a carbon-free fuel: its burning releases greenhouse gases. Yet some falsely claim it can be considered carbon-neutral because trees or other crops used for biomass are replaced, locking in the carbon that has been released by burning. However, addressing climate change is becoming so urgent that we simply cannot afford to wait decades for trees to re-grow, and there are increasing calls for the EU to stop treating biomass as carbon-neutral and to make sure its emissions costs are included in the EU emissions trading scheme.

In addition, biomass cannot really be considered renewable unless strict sustainability standards are in place and are enforced, as its use may lead to deforestation or the replacement of old-growth forests with plantations. Another problem is that the concept of biomass is rather vague and can mean different things. Defining what type of biomass is suitable for large-scale use in district heating systems is important. Sustainability is especially problematic with ‘forest biomass’ and less so when the biomass used as an energy source is made up of wood residue and waste (e.g. residue from furniture production, sawmill facilities, etc.). Yet, more than a third of woody biomass used for energetic use originates from primary wood.

Solid waste

The incineration of waste for heating/CHP is problematic for several reasons. Municipal waste is composed of different fractions, most of which can and should be either prevented, recycled or composted. This is the goal of the EU’s circular economy policy, which includes a commitment to prevent or recycle 65 per cent of municipal waste by 2035. Using waste as a fuel crowds out investments in waste separation and recycling measures.

In addition, burning waste creates air pollution, including carcinogenic substances like dioxins and furans. The composition of waste can be highly variable and in some countries there are no strict standards in place to monitor and control what type of waste is used as energy fuel. It is clear from the experience with existing industrial and energy facilities in the Western Balkans that the authorities are not effective with enforcing pollution control legislation, so it is highly risky to build incinerators. Even where proper filters are used, the ash from the incinerator (about 30 per cent of the weight of the original waste) as well as the highly toxic filter residues, have to be disposed of somewhere, and the Western Balkan countries do not have secure enough facilities for this. In other words, whatever toxic substances are in the waste or are generated during combustion have to end up somewhere – either in the air, ash, or filter residues.

Solutions:

Decarbonise heating through fossil fuel phase-out and modern and clean technologies based on renewables

Governments (central and municipal) need to be progressive in thinking about how to transform their heating sectors. ‘Transitional’ fuels like fossil gas or biomass CHP are false solutions, resulting in dependence on another unsustainable heating source for decades.

Instead, to ensure a high level of comfort and cleaner air, and to achieve the climate and energy targets and fulfil their commitments, the authorities should embrace fourth generation heating. Where feasible and economically justified, district heating systems should be used, as they offer numerous advantages in more densely populated places – scale, efficiency and significant reduction of air pollution. Such fourth generation systems include advanced low-temperature technological solutions of different scales, based on renewables and recycled/reused heat, which can be integrated into existing networks or be used for the design of new systems. Heat pumps are one such solution that is already being promoted, but overall, governments should be looking at diversified solutions based on the local potential for renewables (solar, geothermal, electricity produced from renewables like wind), excess heat recovery from industry and services, and seasonal heat storage.

Even though fourth generation solutions can be expensive to implement, over time they are becoming less costly, and their long-term benefits – including sustainability, no import dependence, clean air, economic growth and the creation of new jobs – greatly outweigh the costs. Such systems are decentralised, combine several sources of heat, and require high and long-term investments – it takes several years to bring them from planning to full operation.

There are many existing fourth generation systems around Europe, primarily in Denmark and the Nordic countries, but also Germany, Italy, etc. In smaller places, the transformation has been easier (e.g. Marstal in Denmark), and in bigger cities like Helsinki, which has an existing district heating system, the transition from fossil fuels has been gradual. What is common to the locations where fourth generation heating already exists is that the full transformation does not happen overnight: it can be done in stages over a period of time, which also helps to spread the costs and utilise local capacities and expertise. Municipal authorities and local communities are the most engaged actors and need to work together on the transformation. Locals are involved through ‘energy communities’ that pool finances, set up collective ownership of district heating networks, engage in prosumer activities, etc.

One example where the transformation of the heating system is underway is a case Bankwatch has been working on in Slovakia. A study was done to propose alternative solutions to the heating provided from the coal-based CHP plant Novaky, scheduled to shut down by the end of 2023. The proposed solution in the study, completed in the beginning of 2020, is to prioritise energy efficiency through savings in buildings and in the distribution network and to combine several renewables based on the local potential, including geothermal, solar energy, heat pumps, and biomass (from the CHP plant), together with seasonal heat storage.

Reduce heat demand through energy efficiency

Without ‘energy efficiency first’, there can be no modern and affordable heating, either in district heating systems or in individual heating. Energy efficiency is crucial for bringing down heat demand, which is needed to reduce costs for consumers.

The Heat Roadmap project recommends overall demand reductions of approximately 30 to 45 per cent of current levels. The Paris Agreement Compatible Scenarios for Energy Infrastructure (PACS) even assume demand reductions of nearly 70 per cent.

Measures for energy efficiency consist of energy efficiency improvements in buildings, especially deep renovation that would lead to substantial energy savings: comprehensive insulation of facades, floors, roofs and windows and air sealing; improvements in the internal distribution systems; and protection against heat in summer to reduce cooling demand. They should also cover improvements to the heat networks (the pipelines and the grid), in order to allow for decreasing the temperature in the networks, which will lead to further energy savings and integration of renewables. In addition, there needs to be an overall shift toward demand-driven systems where users can actively control their consumption. The introduction of metering and consumption-based billing together with adequate control equipment enables consumers to control their heating expenses and motivates them to invest in energy efficiency improvements, as long as it is coupled with appropriate education measures.

Latest news

Bihor County leads Romania’s geothermal heating revolution with EU support

Blog entry | 27 January, 2025Geothermal energy is becoming an increasingly popular way to heat homes and buildings across Europe. Efficient use of this renewable energy source not only significantly lowers heating costs compared to gas-based systems, but also reduces greenhouse gas emissions and improves urban air quality.

Read moreHeating the heights: Žabljak’s bold move towards sustainable warmth

Blog entry | 11 December, 2024Perched 1,456 metres above sea level in the Durmitor National Park in Montenegro, Žabljak, the highest urban settlement in the Western Balkans, is looking for new heating solutions. A 2020 pre-feasibility suggested biomass, but determined to avoid air pollution and deforestation, the local authorities set out to find a better way forward.

Read moreUnfit for 55: How EU climate money is supporting gas-fired heating in Slovakia

Blog entry | 3 October, 2024Despite a marked drop in fossil-gas consumption, Slovakia supported district heating systems to run on fossil gas with EUR 55 million from the EU’s Modernisation Fund.

Read moreRelated publications

Analysis of alternatives to coal-based district heating for the Bitola region in North Macedonia

Analysis | 21 December, 2022 | Download PDFThe study examines the current heating situation in the Bitola region (covering the municipalities of Bitola, Mogila and Novaci), followed by an analysis of the techno-economic potential for using decentralised heating solutions that are also in line with the country’s environmental protection commitments.

Heating from renewable and alternative energy sources for the city of Motru. Solutions and recommendations.

Study | 17 November, 2022 | Download PDFThe study Heating from renewable and alternative energy sources for the city of Motru. Solutions and recommendations. identifies and analyses sustainable heating solutions for the city of Motru, located in Gorj County, Romania. It assesses the current

The EBRD must stay away from the unsustainable conversion of Tuzla’s coal plant and prioritise renewables in the district heating sector

Briefing | 9 November, 2022 | Download PDFThis briefing offers an overview of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s (EBRD) ongoing assessment of whether to grant a EUR 50 million loan in order to replace unit 3 of the Tuzla coal plant with a waste and biomass incineration syst