Just transition

Working on just transition brings all actors who believe in fair regional redevelopment to the same table: unions, industry, public administration, governments, civil society and others sharing this goal. They should be working together to find what is best for their regions and communities, from creating good quality jobs to identifying sustainable alternatives.

Stay informed

We closely follow international public finance and bring critical updates from the ground.

Key facts

- To reach carbon neutrality by 2050, as envisioned in the European Green Deal, a complete decarbonisation of the European economy is needed. Some regions will be impacted by this transformation more than others. Carbon-intensive regions with high employment in fossil industries are at risk of being left behind economically and socially.

- The Just Transition Mechanism is a key EU initiative to provide targeted support of EUR 55 billion to carbon intensive regions.

- The identification of the territories most in need of support from the Just Transition Mechanism is carried out by member states and the European Commission. Member states must prepare Territorial Just Transition Plans (TJTPs) which are sent to the European Commission for approval.

- TJTPs must set out the challenges faced by the regions, as well as their needs and objectives for their transformation processes.

Key issues

- Weak partnership

Transparent processes and meaningful inclusion of local stakeholders are key to producing credible TJTPs with sufficient ambition. It is therefore concerning that many regions have failed to provide stakeholders with the means to have their voices heard. Unrealistic deadlines, weak outreach strategies and in some cases outright exclusion of NGO representatives have affected the process negatively in many Just Transition regions.

- Lack of ambition

Draft TJTPs reveal that many regions are failing to provide proof of sufficient ambition to reach net neutrality by 2050. The plans must be updated with credible timelines for coal phase-out and must get rid of all ambiguity regarding gas and hydrogen-projects.

- Overlooking women and youth

The transformation processes needed to reach net zero will have severe consequences for all groups of society. Yet, many TJTPs fail to provide detailed plans for how adverse effects on demographic groups such as women and youth will be counteracted. The TJTPs must be updated with better strategies for making sure no-one is left behind.

Background

While a phaseout of coal in Europe is inevitable within the next decade, some central and eastern European governments are resisting the trend. Their argument is that coal is key to energy security and economic prosperity, and that workers and communities in coal-reliant regions would suffer greatly if phaseouts are implemented.

Yet a closer look at these coal-dependent regions tells a different story. In many cases, local authorities and citizens in the communities themselves have already started building post-coal futures.

People are out and about planning for the future, in some cases demonstrating an extraordinary level of cooperation between citizens and local authorities.

The mobilisation in these regions shows that a Just Transition of coal regions in central and eastern Europe is possible, following in the footsteps of other regions around the world where citizens, local and central authorities, trade unions and civil society are working together to build alternative futures.

In central and eastern Europe too, a Just Transition has already started.

Blazing the just transition trail

‘Blazing the just transition trail’ takes you on a journey to Poland and Romania, featuring inspiring stories that showcase the progress of the just transition in the EU.

Our video reveals the power of joint action and the importance of community-based solutions.

With 96 regions across the EU set to benefit from the Just Transition Fund, these insights from Poland and Romania are more important than ever for shaping the future of just transition.

Following the money from the Just Transition Fund

Our series of briefings provides key insights into the just transition strategies of eight countries in central and eastern Europe: Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Poland, Romania and Slovakia. Our analysis focuses on the 28 Territorial Just Transition Plans developed for regions within these countries receiving support from the Just Transition Fund. We examine not only the content of the plans, but also how their objectives specifically translate into the allocation of funds. We delve into the economic, environmental and social aspects of the plans and show how investments will be distributed across these policy areas.

Countries that have had their plans approved have advanced to the implementation phase, giving potential investors the opportunity to apply for funding based on priorities set out in the plans. In most countries, monitoring committees have been established to track the use of these funds.

Using the European Commission’s Cohesion Open Data Platform, we calculated the percentage of the total Just Transition Fund budget dedicated to each policy area. The overall goal is to shed light on how the countries and regions plan to spend their Just Transition Fund allocations.

The Just Transition Fund will be allocated between three policy categories: economic, environmental and social1. The economic category covers investments in employment, retraining and upskilling, small and medium-sized enterprises, business incubators, and large enterprises, including research, development and innovation. The environmental category covers investments in renewable energy sources and related infrastructure, energy communities, energy efficiency, land recultivation, waste management, mobility and climate adaptation. The social category covers social services, care for children and older people, research, development and innovation in the public sector, education and small-scale community initiatives.

However, funding priorities for the just transition vary significantly across the eight countries. For instance, while the Czech Republic demonstrates a balanced approach, allocating resources almost equally across economic, environmental and social policies, Romania’s unbalanced approach heavily prioritises economic policies to the detriment of environmental and social initiatives.

Overall, economic and environmental policies receive the most funding and are seen as top priorities by most countries. Regrettably, the social impacts of the just transition receive far less funding or are even ignored entirely, such as in Bulgaria, Hungary, Latvia and Romania.

Heavy investment in large enterprises can limit economic diversification at the local level, potentially locking economies like those of Estonia, Bulgaria and Hungary into their existing mono-industrial models. While Estonia compensates by prioritising investments in small and medium-sized enterprises, this is not the case in countries like Bulgaria and Slovakia. And although Romania has a strong focus on small and medium-sized enterprises, business development could be hindered if not paired with investments in skills development, research and education. Investments in energy policies vary significantly between countries. Even in Bulgaria and Slovakia, where investment in large enterprises is high, funds are being allocated towards renewable energy, waste management and energy efficiency.

The huge gap in funding for social measures (beyond job losses in transitioning industries) indicates that the broader social impacts of the just transition will likely require additional support from other funds, such as the European Social Fund or the Social Climate Fund. Similarly, nature restoration projects aimed at increasing biodiversity within former industrial areas may also need to seek funding from other cohesion policy funds or future dedicated environmental funds.

All eight countries chose to direct funds towards employment or retraining/upskilling. Poland, Bulgaria and Romania are the countries expected to be most affected by job losses in the coal industry so they will invest most in these types of interventions. One worrisome aspect of this allocation is the fact that in some countries most of this allocation will go towards the Reemployment Agencies, who can sometimes be inefficient.

Allocating funds aimed at covering the gaps created by job loss is crucial to a successful just transition. Still, this is only part of the story, as marginalized communities in these regions are in greater need of support aimed at improving their inclusion in the workforce. In most carbon intensive regions, workers in the polluting industry tend to be one of the more privileged social groups. In addition, employment schemes are frequently implemented in order to alleviate the economic impacts of such transitions and as economic stimulus measures.

Investments in renewable energy, infrastructure and energy efficiency dominate the environmental allocation from the Just Transition Fund. In Latvia, Hungary, Poland and Bulgaria, the recultivation of former mining sites and degraded land is a key priority. There are less significant allocations for mobility in Latvia, Poland and Romania, but circular economy and climate adaptation projects receive little or no attention. Investments in energy communities have been totally ignored, with some counties suggesting this area will be targeted using other funds. However, the complete absence of funding signals a lack of interest in the topic and makes tracking these investments difficult. It is also concerning that allocations for nature restoration and biodiversity, areas that demand the urgent attention of most countries, have been entirely overlooked.

1 Economic policies were defined as those directly aimed at the private sector or the improvement of employment conditions. Employment policies were also grouped under economic policies due to their primary benefits for companies or individuals. Economic policies encompass initiatives such as investments in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), workforce retraining or upskilling, and investments in large businesses. Environmental policies were defined as those that aim to enhance the environment, including increasing renewable energy production and brownfield decontamination. Social policies were defined as those intended to improve the communal and public conditions of regions and specifically benefit large segments of the population. These policies cover investments in social and healthcare, education (excluding retraining or upskilling) and public research organisations.

For a detailed country-by-country analysis, check out our briefings:

Innovation, cooperation and participation – best practices from the Just Transition regions in central and eastern Europe

Just Transition regions in the Central and Eastern Europe have not been discouraged by their limited resources and experience. Two years after the creation of the Just Transition Fund, many regions are now putting the final touches on their Territorial Just Transition Plans (TJTP) required for accessing the funds. Bankwatch has been keeping tabs on especially inspiring initiatives and ideas being proposed locally.

The Just Transition Platform

The Just Transition Platform has grown out of the Coal Regions in Transition Initiative (popularly referred to as the Coal Platform), developing and expanding on the support provided by the latter to transitioning regions, such as technical assistance. The Just Transition Platform is a space for the exchange of information and experiences, as well as for discussing issues linked to the Just Transition process throughout the European Union, with regular physical (if possible) and online meetings on relevant topics.

In Autumn 2021, 4 working groups were established in the Platform to develop implementation papers on a horizontal stakeholder strategy, but also general transition strategies for cement, chemical and steel regions in Europe. The working groups consist of a wide variety of stakeholders representing different groups of interest, to make sure the process is as inclusive as possible, though so far industries are overrepresented in the cement, chemical and steel working groups.

Just transition in the region

There are three Territorial Just Transition Plans under development in Hungary for the regions of Baranya, Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén and Heves. The plans have been accepted on national level, submitted to the EU Commission. The first round of negotiations is underway. The TJTP will be Chapter 5 of the Environment and Energy Efficiency Operational Programme Plus (KEHOP Plus) – so a standard OP procedure is foreseen.

The process has been generally satisfactory with regards to partnership and inclusion in 2021, but no public details are available on the current EU-Hungary negotiations.

The main challenges have been the lack of availability, lack of capacity and lack of capacity-building activities for local stakeholders. The inclusion, enabling and motivation local stakeholders, NGOs, municipalities and citizen interest groups would require way more efforts.

These planned transitions are consistent with the National Energy and Climate Plan and other relevant mid-term strategies, but the main concern is that the National Energy and Climate Plan itself is not ambitious enough. In particular, this is due to an envisaged reliance on fossil gas and nuclear energy sources until 2050. Hungary has committed to a closing down its last remaining coal fired power plant – the MVM MATRA power plant, not only by 2030 but already 2025. To ensure a Just Transition of the Hungarian coal regions, it is vital to keep the pressure on the government to deliver on its promises.

There are six Territorial Just Transition Plans under development in Romania. The Plans are for the Hunedoara, Gorj, Dolj, Galati, Prahova and Mures regions. Bankwatch has been actively involved in the coal regions of Gorj and Hunedoara and has participated in the working groups meetings between local level decision makers in the two regions.

Romania has set a 2032 deadline for coal phase-out and a lot of work is needed to get there. More than 25 % of the electricity produced in Romania comes from coal mines and the local economies in the coal regions are dependent on the industry. A strong emphasis on Just Transition is clearly needed.

Unfortunately, the Romanian draft Territorial Just Transition Plans remain quite weak. The Plans do not provide sufficient detail or timelines for the transition processes. Moreover, the Plans contain uncertainty regarding the implementation of the transition, primarily due to repeated references to gas as part of the solution.

In Jiu Valley(Hunedoara county) the civil society has been involved in the just transition process for quite some time. As a result of their work, the governance of the just transition will be unsured by an independent organization comprised of municipalities, university and NGOs. On the other hand, as civil society in Gorj is quite weak, there is still a lot of room to grow regarding their involvement in the just transition process.

Czechia has one Territorial Just Transition Plans, covering the Ustecký, Moravskoslezský and Karlovarský regions.

The Plan prepared by the Ministry for Regional Development in a collaboration with the Czech Transformation Platform, set up in late 2020, which is an advisory board that involves experts from labour unions, local governments, NGOs, politicians and the industry. It consists of representatives from 32 diverse subjects. The platform is responsible for preparing and implementing the Just Transition Operational Programme as well as setting up a participative process for the development of the Territorial Just Transition Plans. The coal industry and Ministry representatives have a strong presence in the platform, whereas the NGO sector has only a single representative.

There are certain other issues with the just transition process in Czechia, since it is lacking basic communication and participation of the general public. The term “just transition” is still weakly understood and thus there is low interest on both the national and regional level.

December 2021 has brought a significant turning point while new government’s programme determined year 2033 as a coal phase-out date. Thus, the Czech Territorial Just Transition Plan should be more precise in its description of the decarbonization timeline and is supposed to refer to this date while planning. The Plan is, however, nowadays still consistent with the outdated Czech National Energy and Climate Plan, which is not very ambitious and has not been updated to reflect the 55 per cent emission reduction target for 2030 adopted at the EU level in 2019. The Plans are currently too vague and too light on real commitments, such as rules to ensure polluter pays principle, realistic and feasible decarbonization pathway of heat and energy sector and measures against energy poverty.

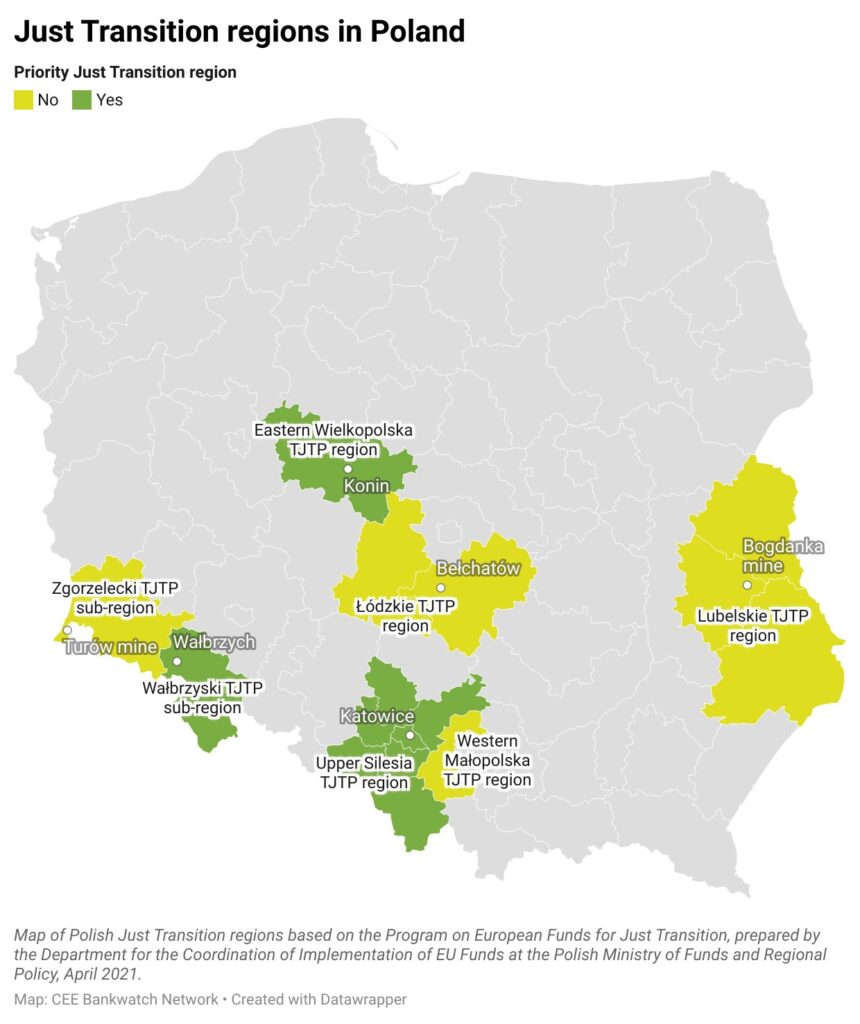

Poland has drafted Territorial Just Transition Plans for five regions, including Eastern Wielkopolska, Upper Silesia, Lubelskie, Łódzkie and Western Małopolska, and for the two subregions Wałbrzych and Zgorzelec (both located in the Lower Silesia voivodeship). However, only the regions of Eastern Wielkopolska and Upper Silesia, as well as the Wałbrzych subregion, have been approved by the European Commission to receive assistance within the scope of the Just Transition Mechanism. The remaining regions have yet to be accepted and remain hopeful.

Eastern Wielkopolska joined the Platform for Coal Regions in Transition in April 2019, presenting its first batch of green project proposals to replace the lignite economy in the longer term. However, in the meantime, actions on the ground accelerated, with ZEPAK, the owner of the lignite mines and power plants, announcing its first mass layoff, and since then the company has advocated for more support for its employees who will be laid off in the upcoming months and years. For now, there are no emergency plans on how to help the miners who will lose their jobs, and what makes matters worse is that lignite miners, unlike the hard coal miners working for state-owned mines in Silesia, are not entitled to any special social security measures in the event of redundancies, such as one-off payments or transfer to early retirement.

In Upper Silesia, the standoff between the local community and the mining company continues as neither side is ready to cede ground. The recently unearthed plans to start new mining operations in Rybnik, Jastrzębie Zdrój and Bytom have prompted a similar mobilisation of local people. Last year, there was also the issue of the Turów mine and conflicts surrounding the trans-border conflict between Czechia and Poland over continued mining that endangered the underground water supplies.

Meanwhile, Poland has not improved its ambition in terms of its coal phase-out date (the latest announced date is 2049), but has said it would back climate neutrality if provided with generous financial assistance to support a just transition. Logically, this means that Poland has to start planning its transition away from coal, possibly modify its own draft plans and strategies that currently foresee keeping the current share of coal in the mix for at least another two decades, and, perhaps, rethink its insistence on pushing through new mining projects.

In July 2019, Slovak government approved the ‘Transformation Action Plan of coal region Upper Nitra´. It was prepared by the regional parliament and by local communities in 5 public hearings organized in the region. The document is finally largely based on inputs from local communities in Upper Nitra, who have been organising in working groups to prepare scenarios for the transformation of the region since 2018.

In June 2019, Slovakia announced that it supports the EU 2050 carbon neutrality goal and said it would end electricity production from coal burning by 2023.

Since then, Slovakia has been developing Territorial Just Transition Plans for the Upper Nitra, Banskobystrický and Kosický regions. The Plans were submitted to the European Commission on 16 November 2021. Most of the analyses of the Just Transition process done so far have been based on the Slovak Action Plan mentioned above.

Bulgaria seems to be omnivorous when it comes to new fossil fuel infrastructure. Between gas pipelines, new oil and gas exploration in the Black Sea, LNG terminals, subsidies for households to switch to gas, there remains considerable work to be done.

It is therefore worrying that the Bulgarian government has stated that the country has a horizon of 60 years of coal reserves at the current rate of use and that the reliance on coal is unlikely to change before 2030. It provides a glimmer of hope, however, that Bulgaria has agreed to phase out coal by 2038 or 2040 as part of the COVID-19 recovery package negotiations in October 2021.

In terms of Just Transition, the Bulgarian situation remains complicated. There are three Territorial Just Transition Plans under development in Bulgaria in the Stara Zagora, Pernik and Kyustendil regions. Due to months of political instability the country’s Just Transition process has been delayed significantly. A permanent government was not established until December 2021. Progress is expected in the coming months, but approval of TJTPs is not likely before the 4th quarter of 2022.

The Ida-Virumaa region in north-eastern Estonia is the only Just Transition region in the country. Estonia is quite advanced on Just Transition and the Ida-Virumaa Territorial Just Transition Plan is expected to be among the first to receive approval from the European Commission within the next few months.

The Estonian Territorial Just Transition Plan is generally one of the better ones, but problematic sections still remain. For example, the Just Transition Plan has not been updated to comply with new EU climate targets. The plan is only consistent with the National Energy and Climate Plan from 2017 which is widely regarded as outdated. The plan also fails to provide clear evidence of a transition process in Ida-Virumaa before 2030, namely due to a lack of clarity regarding the phase-out date of oil shale in the region. Moreover, although the Plan notably focuses on diversifying the economy, there is a limited emphasis on supporting small emerging start-ups and business creation. Finally, while the Plan recognizes the issues regarding the underrepresentation of various social groups, no clear steps have been proposed to overcome the challenges.

It is therefore of the highest importance that stakeholders and civil society continue to apply pressure on the national authorities to ensure that the Plan benefits those that need it most.

RegENERate: Mobilising Regions for Energetic Re-development and Transformative NECPs

The overall objective of the project is to support the CEE countries’ contribution to the EU efforts towards a net-zero emissions future. The project will contribute to more ambitious and effective climate and energy policies in CEE, backed by a long-term commitment to phase out fossil fuels, improve energy efficiency and promote renewable energy.

The project will build on the Bankwatch Network’s recent work on just transition and energy transformation in the CEE countries. It will deepen previous cooperation with stakeholders to proactively engage in developing governance instruments and ensure financial means for the implementation of the NECPs at the national and local level. The approach of integration of NECPs in local level planning will be further developed through the project to become a methodology for the integration of climate objectives through a community – led process. These existing collaborations will form a key part of our means of attaining our objectives.

RePower the Regions: Ambitious and inclusive clean energy plans for repowering the just transition regions

The participation and leadership of carbon-intensive regions in transitioning to clean energy solutions are prerequisites for achieving EU climate neutrality by 2050. Building on this premise, RePower the Regions aims to ensure that the regions’ clean energy plans are aligned with EU 2030 climate goals and have strong support locally, and to provide practical guidelines and roadmaps on how to repower the regions.

Latest news

ЦИЕ все още изостава в ангажиментите си за енергийния преход

Bankwatch in the media | 7 June, 2021Липсата на по-амбициозни стратегии в страни като Чехия, Румъния и Полша помрачава амбициите на ЕС за поетапно премахване на въглищата

Read moreLack of coal phase-out commitments in Eastern Europe jeopardises just transition

Bankwatch in the media | 7 June, 2021Unambitious coal phase-out policies in central and eastern Europe threaten the just transition in the region and the European Commission …

Read morePublic engagement still lacking in coal regions’ transition, NGOs warn

Bankwatch in the media | 4 June, 2021Despite being a requirement, public consultation remains inadequate as Central and Eastern European (CEE) regions draw up the plans to …

Read moreRelated publications

Supporting the just transition through dedicated technical assistance

Briefing | 28 June, 2024 | Download PDFThe just transition implementation phase is underway. However, additional support is needed to drive implementation and help projects respond to their particular challenges. This briefing provides recommendations for supporting the just transition process with technical assistance, capacity building, project preparation and project funding.

Local authority planning for a just transition: Why Western Balkan coal regions should create their own redevelopment plans and how it can be done

Report | 26 April, 2024 | Download PDFFrom December 2020 to December 2023, the European Union implemented its first Initiative for coal regions in transition in the Western Balkans and Ukraine

Following the money: Poland

Briefing | 22 April, 2024 | Download PDFThis briefing provides an overview of the just transition envisioned in the Polish Territorial Just Transition Plans for the four regions designated to receive money from the Just Transition Fund.