Paving over paradise

Khada Valley, Georgia

by Rusudan Panozishvili, Bankwatch

What were once iconic views of Georgia’s beautiful Khada Valley are slowly disappearing. Now, when you drive up the damaged road towards a narrow, 12-kilometre-long gorge, also known as the ‘valley of 60 towers’, the first thing you see is no longer the famous tower of Iukho village. Instead, a massive, white and blue metal construction site appears. Trucks, roaring and echoing through the mountains, drive back and forth near cultural heritage monuments to provide materials for the Kvesheti-Kobi road towards Russia.

But scientists fear that it is not only the views that will be damaged by this massive infrastructure project.

Despite complaints from the local population and experts on cultural heritage, tourism development, and other areas, the construction of the controversial North-South Corridor (Kvesheti-Kobi) Road has started. On October 2021, the Georgian government and international bank representatives festively kicked off the digging of a 9-kilometre tunnel in in Kobi. This tunnel will link Kobi with the area of Zakatkari near Khada valley, which although it has not been studied by archeologists for the road project, nevertheless contains human traces from the Neolithic era.

The North-South Corridor Road project is funded by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and implemented by the Roads Department of Georgia. The total cost will be up to USD 558 million, with the EBRD issuing a USD 60 million loan and the ADB a USD 415 million loan. The road envisages the construction of five tunnels and six bridges.

‘While the Kvesheti-Kobi Road Project is ongoing, the numerous issues and concerns that were reported previously are still unresolved, and [the lack of] proper assessment studies [is] problematic along with the construction activities… The concerns of local communities and experts about the potential impact of the project on cultural heritage went unheard during project preparation. The project sponsor did not study Khada’s cultural heritage thoroughly… The field experts were not involved in the baseline studies or during the impact assessment process’, revealed a fact-finding mission to Khada valley conducted by CEE Bankwatch Network and Green Alternative in July 2021. According to their report, the project concerns include the impact of the construction on cultural heritage and archaeological sites, biodiversity and local communities.

‘Tskere village… has an incredibly rich historical past’, says Peter Nasmyth, co-chair of the National Trust of Georgia, standing in front of the 9-kilometre tunnel that is being constructed less than 100 meters from one of the oldest and most valued historical villages in Khada valley. ‘Archeologists have found traces of settlements here [from the time] before Christ… This valley has been inhabited for thousands of years…This is such an old church. When they start digging, we fear that it will collapse, because of the vibrations of the tunnel. We also have some concerns [about] avalanches here’, Nasmyth concludes.

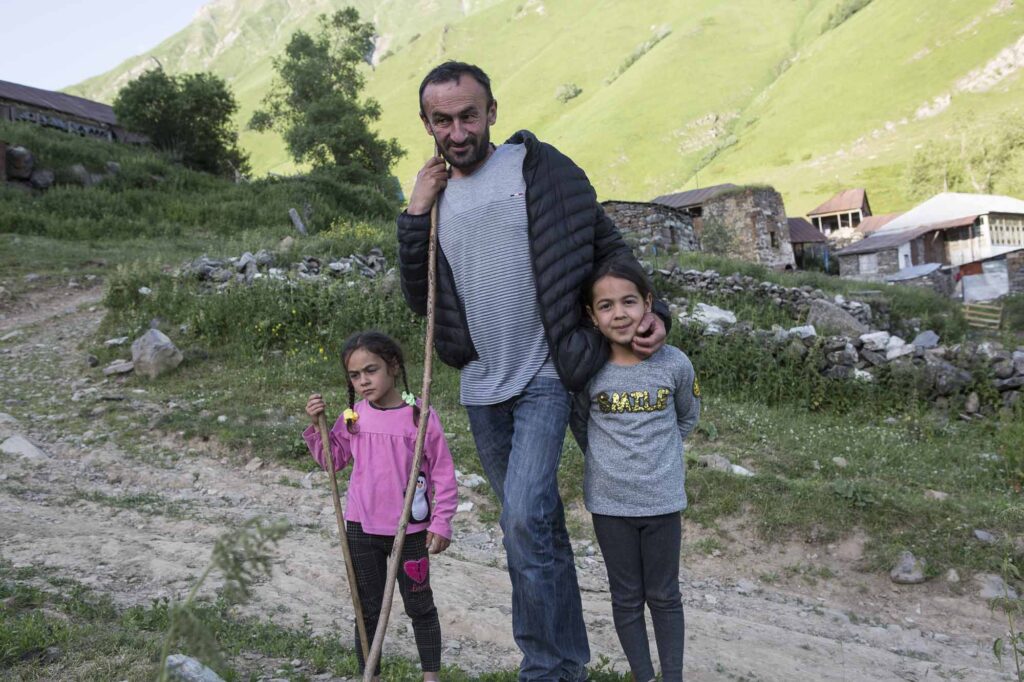

Zviad Zakaidze lives in Tskere and he is raising his three daughters there, too. The three girls, with yellow and white bows in their hair and wooden stakes in their hands, confidently make sure the cows don’t go too far while their father takes a break to give an interview to Bankwatch and Green Alternative.

‘This is the place of my ancestors. If it is not important, then what is important for me?’ said Zakaidze, adding that he would prefer to maintain his ancestors’ land over receiving compensation for the road if he had a choice.

‘It is precious because I have what they [my ancestors] left for me. I was born and raised here… I have my churches here, the dead are [buried] here, the alive are here. The road is good, but things should not be managed badly. Things should not be damaged. Our houses, our churches and castles come first.’

The mountain where the historic cemetery and cherished church of Zakaidze and his villagers sit will be drilled to build the tunnel. The cultural heritage monuments, dwellings, and most of the old houses in Khada are built with an old, dry-stone method. Scientists and locals fear the drilling will cause the cultural heritage sites to crack and will ultimately destroy them. The report by Bankwatch and Green Alternative concludes that: ‘Unfortunately, the proposed and approved ESIA does not offer either a proper assessment of potential significant adverse impacts, or effective measures to decrease the impact on those buildings.’

In 2020, the UNESCO-associated organisation International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) declared that Khada valley’s cultural heritage is at risk due to the Kvesheti-Kobi Road Project.

34 or 155? Chaotic studies of Khada’s cultural legacy

‘This is another site where those archeologists were working this summer’, says one of the locals (who does not want his name revealed), as he leads us to an abandoned pile of large stones arranged in circles. He explains that the archeologists thought this could have been the ruin of a castle from before the time of Christ. Locals were helping the scientists who worked in Khada after the project contractor was required to launch additional archeological studies in the valley. But, the locals say, one day all the archeologists ‘disappeared’ and ‘never came back’.

In 2019, the Georgian government issued an environmental permit for the construction of Kvesheti-Kobi road, which contained only a general overview of heritage studies in Khada valley. The report identified 34 cultural heritage sites and objects in the area.

However, scientists objected that the permit did not contain a thorough investigation. Because of their pressure, in 2020, the government of Georgia funded another round of cultural studies in Khada, after which 155 new historic sites were found. What these new sites are, how they will be affected by the construction and the plan to protect them remain unknown. The results of the new studies have not been published yet.

But the Georgian government and the construction company do not seem to care much about how to save 155 heritage sites in the Khada valley. Because, while this information is still pending, the construction continues.

Bankwatch’s fact-finding mission this summer revealed that in Khada, near the village of Beniani, ‘the archaeologists found numerous ruins. The location of these ruins, as well as some underground tunnels in their vicinity and other cultural heritage monuments (a church and old cemetery) indicate that there may be a large, undiscovered historical complex located directly on the road’s proposed route.’

Therefore, the report suggested that ‘[in-depth archaeological and cultural heritage studies must be conducted in the valley by qualified international experts. The transparency of these studies is essential in this case. A wider expert group should be involved in the process, and changes to the project’s design should be carried out based on comprehensive consultations, inventory, and other studies.’

The locals have not been informed about whether the newly identified archaeological sites and objects have been included in any report or if anyone is working to protect them while Kvesheti-Kobi construction is in full swing.