Bankwatch Mail 47

Bankwatch Mail | 15 April 2011

Content

(Click on titles to read articles online)

- Abuses continue in Moscow as development banks give up on Khimki road financing

- Local pressure in Lithuania keeps EU funds out of the waste incineration fire

- It’s the EU funds, stupid, and the green economic dividends they offer

- BTC under fire for violating human rights obligations and pipeline integrity issues

- Hunting for sustainability in Hungary

- Roads that rob us: no accountability for infrastructure development in Azerbaijan

- EU funds at the heart of yet another Czech political corruption scandal

- EU Funds on the line – road lobby attempts to derail sustainable transport development in Poland, Slovakia and the Czech Republic

- World Bank sponsored privatised pension pillar crumbling in Poland

- Austerity is the mother of rising dissension in Romania

- Why the new EIB tax haven policy will not be effective

- Split signals on EIB’s lending outside Europe

- Big lending numbers, big banks … and still big question marks

- What is the EBRD?

- Replaying an old record, as Bankwatch provides input to latest review of EBRD public information policy

- Financial mountains out of energy saving molehills in Ukraine

1. Abuses continue in Moscow as development banks give up on Khimki road financing

Unequivocal confirmation arrived from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) in the new year that it would not be getting involved in project finance for the Khimki Forest section of the Moscow – St. Petersburg motorway. In the final quarter of 2010, the European Commission intimated to Bankwatch during a meeting in Brussels that neither the EBRD nor the European Investment Bank would be proceeding with project appraisal for the highly controversial Khimki section of the motorway.

The EBRD’s announcement followed a bruising and bloody period last autumn in the unfolding saga of the motorway construction in the forest on the outskirts of the Russian capital. Activist defenders of Khimki Forest and a high-profile Russian journalist were attacked and severely beaten, the motive for the attacks being widely linked to expressions of support for keeping Khimki Forest, the so-called ‘lungs of Moscow’, a motorway-free zone.

Yet regular shenanigans continue to affect the Khimki Forest protestors. In February police in the Khimki district arrested activist Alla Chernyshova, and her daughters of 3 and 6 had to spend more than five hours in custody where she was questioned as the main suspect for a false bomb threat. Ironically the supposed alert had been used by the the very same police to prevent demonstrators and media from entering the Khimki construction site on February 1.

A public environmental assessment, handed over to President Dmitry Medvedev on February 1, has found that widening the existing highway, outside Khimki Forest, is the best alternative for realising the motorway. The assessment was initiated by a coalition of environmental NGOs and carried out by 18 experts in the field of environmental protection, environmental law, forestry, urban planning and transport development.

The overriding obstacle for the campaigners and their arguments, however, remains in the form of vested commercial interests determined to cash in on the long-planned commercial development of Khimki Forest, one of the few natural areas left for inhabitants of the wider Moscow area.

While the motorway section through Khimki Forest is, therefore, to receive no funding from European public banks, there is increasing speculation that the EBRD has confirmed its readiness to get involved in other sections of the Moscow – St. Petersburg motorway. Whether these other sections will be free of the violent, underhand tactics that have been an unfortunate hallmark of the Khimki Forest section remains highly uncertain.

The prominent Khimki activist Evgenia Chirikova, herself no stranger to harrassment and arrest in recent years because of her defence of the forest at the heart of her local community, received recognition of her fearless campaigning earlier this month when she accepted a US Woman of Courage Award from US Vice President Joe Biden during his visit to Moscow. Chirikova raised the problematic aspects of the Khimki section of the motorway directly with the EBRD’s president Thomas Mirow during a civil society dialogue at the bank’s annual meeting in Zagreb last May, securing pledges then from Mr Mirow to investigate the case further, a case whose controversies the bank’s president appeared to be relatively in the dark about at that stage in its history.

Read more:

A catalogue of the repression meted out to Khimki activists over the years is available in English at the website of the Defenders of Khimki Forest

2. Local pressure in Lithuania keeps EU funds out of the waste incineration fire

Three municipal waste incinerators, planned for development with significant EU structural funds support in Lithuania’s biggest cities Vilnius, Kaunas and Klaipeda, have in recent months been blocked thanks to mobilisation efforts from local communities and environmental NGOs, including Bankwatch member group Atgaja Community.

Anti-incineration voices have successfully pointed to increases in environmental pollution and waste management costs per household that are expected to accrue from the introduction of the controversial waste management technology. At the same time, they have argued that support for the proposed incinerators via both EU and national funds would negatively impact on the introduction of other more sustainable waste management measures while restricting the development of recycling, as new incinerators would insist on the channelling of waste, almost undoubtedly at higher volumes, to such facilities for decades to come.

Despite the fact that 450 million Litas (equivalent to EUR 130 million) was assigned by the Lithuanian government in its list of ‘major projects’ under the EU Cohesion fund for 2007-13 for two waste incineration projects in Vilnius and Kaunas, neither plan will now receive direct EU financing. Campaigners have instead called for realistic waste management plans for the region – without waste incineration.

Local resistance pays off: transforming waste incineration into more sustainable waste management plans

The involvement of the EU funds in Lithuania’s waste management sector is, as a result, set to reap positive environmental dividends. More funds are available for other Lithuanian municipalities, with ten regional waste management plans totalling EUR 310 million now submitted for EU funding (the EU financing component of these plans is EUR 235.5 million). Of these, many of the municipalities plan to separate their waste in Mechanical Biological Treatment (MBT) facilities. The management of biodegradable waste and better recycling to meet EU targets are key objectives for all of the municipalities. As the municipalities are lagging behind schedule for the current EU funding period 2007-13, project implementation will start soon in 2011.

Under the original Lithuanian EU Cohesion Fund planning for the 2007-2013 period, waste incineration projects were to the fore and included into the national list of major projects. The Vilnius municipality for one was planning a waste incinerator with an annual capacity of 250,000 tons. Kaunas, Lithuania’s second city, had an incinerator with capacity of 80,000 tons per year in its sights. In Klaipeda, Lithuania’s third largest city, the Finnish company Fortum’s long- term plan has been to build a waste incinerator with annual capacity of 150,000 tons. The projects in all three cities were planned in tandem with existing thermal power plants, with heat production for municipal central heating systems and some electricity generation. The projects were at different stages of development prior to submission for EU financing.

EU funds exclusively for sustainable waste management in Vilnius

A Lithuanian company ‘Rubicon group’ (later renamed to ICOR) has been actively promoting waste incineration tied with the Vilnius thermal power plant and Vilnius central heating system since 2007. The 250,000 ton Vilnius incinerator was to be developed with involvement too from the French company ‘Constructions Industrielles de la Mediterranee’ (CNIM), as well as hoped for EU funds. However, concerns about the incinerator plans sparked protests in the surrounding neighbourhoods, and more than 5,000 people signed a petition in 2009 against its construction.

Protests and a concerted campaign against the Vilnius waste incineration plans went on for four years, with calls for a wholesale revision of the Vilnius regional waste management policy. As a result of this pressure, Vilnius Regional Environmental Protection Department commissioned an independent evaluation of the project’s environmental impact assessment (EIA) report, which was carried out by the Lithuanian branch of Swiss company ‘CSD Ingenieure und Geologen’, and based on the conclusions of this evaluation of the EIA report, alongside negative public opinion, the Vilnius Regional Environmental Protection Department of the Ministry of Environment took the decision to reject the EIA report in late 2010. Following this, CNIM and ICOR announced their withdrawal from the Vilnius project, saying that they would be focusing instead on a project in Klaipeda.

Vilnius municipality then prepared a new regional waste management plan for Vilnius County, estimated to cost EUR 38 million, with EUR 29.4 million of this to be covered by EU Cohesion Fund money. The plan was agreed with the Environmental Project Management Agency and signed on December 27, 2010. Waste incineration, not a mass burner as before but instead now to involve the burning of refuse-derived fuel (RDF) after recycling, is still an integral part of this new waste management plan. However Vilnius municipality and the Vilnius Regional Waste Management Center have made it clear that the RDF facility is not subject to EU funds – only municipal waste collection, separation and recycling facilities are to be covered by EU money.

The new waste management programme will include, specifically, the collection and treatment of biodegradable waste and the production of biogas for Vilnius’ public transport. Individual composting of green waste is to be promoted in households, and the city’s main waste stream will be separated in special containers and further in a recycling facility.

The waste incineration plant for RDF, with estimated costs of EUR 130 million, is expected to be financed by a private investor. Both a new EIA and planning process will be required for it. Yet there is now a strong tide of public opposition to waste incineration in Vilnius, and the city’s recently elected council will need to work in tandem with the local community on the implementation of the city’s waste management systems and the controversial incineration component, even if it is RDF technology.

Kaunas incinerator plans don’t add up for environment or taxpayers

The battle against waste incineration in the Lithuanian capital has been mirrored by local resistance against similar plans in Lithuania’s second largest city, Kaunas, with activists from both cities regularly co-operating and sharing experiences. The Kaunas municipality has been focusing all of the city’s waste management plans on waste incineration for years. The main driving forces were the promised EU funds for large scale incinerators and the aspiration to achieve independent energy production from Kaunas Power Plant, owned by the Russian energy giant Gazprom.

Discussions, lobbying and local resistance were kept up for several years, and were finally rewarded in 2010 with the cancellation of the waste incineration project, before it had reached the EIA stage. In its place the Kaunas Regional Waste Management Center (RWMC) submitted a proposal to finance a regional waste management plan in 2010 with total costs of EUR 38.7 million, of which EUR 29.8 million would come via EU support. The new plan puts the emphasis on separation and recycling, with an MBT facility as the main investment. The Director of Kaunas RWMC noted that an evaluation had suggested that the previously planned waste incineration facility would have cost EUR 142 million, a much more expensive solution that would have required increases in local taxation.

Incineration promoters seek a port and cause a storm

The decision to build a waste incinerator in Klaipeda, a sea port city, was approved by the local municipality in 2006. The Finnish company ‘Fortum’ has a long term rent agreement for the city’s central heating system, and plans to invest in a thermal power plant with accompanying waste incineration capacity of 150 000 per year. A new company ‘Technology projects’, formed by the two companies that lost out in Vilnius, ICOR and CNIM, declared an interest in waste incineration in Klaipeda soon after the loss in Vilnius. And for both companies this is not only about local and regional waste management solutions – they are interested in importing waste through Klaipeda port.

Clashes have arisen, however, between Fortum and Technology Projects over the tender for the project, with both proposing different locations, and both facing opposition from local residents. Indeed, one location was cancelled by Klaipeda district municipality due to sharp protests from the local community.

Inspired by the activist victories in Vilnius and Kaunas, the protests from local communities in Klaipeda are growing. The future of the Klaipeda waste incineration project is not clear, nor is the status of the potential EU funding allocation for the project. The anti-incineration campaign is set to continue in Klaipeda, and is gaining more support from NGOs, politicians and the general public. Sustainable long-term waste management solutions need to be found for the city, either with or without EU funds.

Overall in Lithuania, then, these strong and effective campaigns against waste incinerators have raised general public interest about waste management practices, especially when it comes to the adverse health impacts associated with incineration – people now know about the dangers of dioxins. Above all, the need for better recycling, reuse and other environmentally friendly waste management practices are now well understood – the Lithuanian public expects to see them delivered in the upcoming regional waste management plans for every municipality.

3. It’s the EU funds, stupid, and the green economic dividends they offer

Investing European structural and cohesion funds in energy efficiency and renewable energy sources could be helping right now to liberate central and eastern European countries from looming energy crises; but instead of acting, heads of governments are hesitating and clinging on instead to the tried, tested and failed economic growth paradigm.

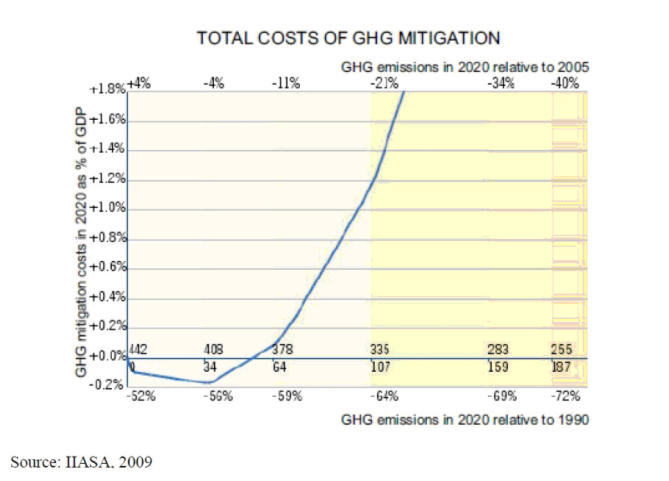

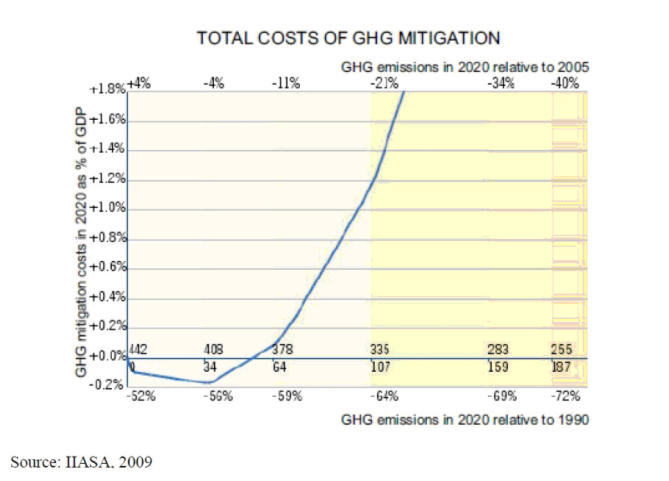

Even though the ten new member states of the European Union have improved their energy efficiency in the past 20 years, and are narrowing the gap with the old member states (partially due to the break down of Soviet-era heavy industries), further reductions in energy intensity and consumption as well as the development of renewable energy sources are required. Stacked against the considerable remaining potential for energy savings and greenhouse gas emissions reductions in the central and eastern Europe (CEE) countries, we find: the countries’ dependency on energy imports, the looming price explosion for fossil fuels and the dead-end paths of other so called “low carbon technologies” (nuclear energy and carbon capture and storage). Weighing in above all is the unforeseeable, but likely far-reaching, impact of fossil fuels driven climate change. Brokering an immediate turnaround in energy consumption and generation has become vital for the countries of CEE. Yet the reconstruction of Europe’s energy supply and the improvement of electricity infrastructure requires huge, long-term upfront investments of up to EUR 900 billion by 2020, according to official European projections – in any language that is money which is currently scarce in a region hit hard by the financial crisis and caught in the public debt trap. So why not tap into the Brussels solidarity jar, otherwise known as the EU structural and cohesion funds?

The European Commission’s multi-billion euro draft budget for Cohesion Policy 2014 to 2020 is to be put forward in June for initial discussion by member states and MEPs. A currently projected EUR 344bn for the 2007-2013 period, nearly one third of the entire EU budget, is being allocated to the EU’s Cohesion Policy, and more than half of this (EUR 177 billion) is set to flow to the new member states. Only a very marginal amount of this total, EUR 4.2 billion, looks likely to be spent on sustainable energy, however.

In light of the emerging squabbling and recriminations around the size of the next EU budget for the 2014-2020 period, there is no chance of a big increase in the overall EU budget for funding the increased investment needs for energy savings and renewables in CEE. What there is, though, is the opportunity to fund such necessary increases through a rechanneling of the EU structural funds, even in the current programming period, as was surprisingly clearly articulated and recommended in a recent communication – “Regional Policy contributing to sustainable growth in Europe 2020” – by the European Commission.

What we continue to see, though, is the CEE countries hesitating in the midst of this golden-green opportunity. Part of the reason for this is the traditional emphasis of the structural and cohesion funds on integrating poorer regions to take part in the single market, through improvements to infrastructure (mainly roads), transport and telecommunications rather than house insulation or green electricity. Another underlying reason, not going out of fashion, is the assumption by politicians that a better political return is provided by using available EU funds for road transport rather than energy efficiency: constructing a highway and having a delightful inauguration photograph in the press is still deemed to be more attractive than installing invisible insulation.

This has to change. A good opportunity could have been the meeting of EU heads of states on February 4th for the extraordinary European Council on energy. But the EU once again missed a chance to set the course for a more sustainable energy and climate policy in Europe. Hopes that this council would bring the EU closer to such a commitment were dashed, with no words about alternatives to the current energy and climate policy, for example EU commitments to at least a 30 percent GHG reduction target, a binding energy saving target or obligatory climate priorities in the future Cohesion Policy. The fact is that a majority of heads of government believes that such a decision could damage the economic development of their countries.

At the same time they all have to be cognisant of the fact that these delays in reducing energy consumption can only cause much higher costs in the future. According to Europe’s most senior politicians, the high risks of this business as usual policy can be offset through intensive networking with Russia and other energy suppliers, for example the oppressive Central Asian states. The possibility to reduce energy dependency through energy savings and widespread exploitation of renewable energy sources are pushed to the side within this kind of logic. Moreover, at the European Council on energy, pressing events ended up overtaking the main agenda: the situation in Egypt and the Euro crisis ended up dominating proceedings, while decisions on major investments for smart energy infrastructure, for example, remain remote.

Yet, what is happening as a result of the political turmoil in Egypt and elsewhere in North Africa? Oil prices are spiking.

In some quarters at least, this is providing momentum to address underlying concerns regarding European dependence on fossil fuels. In the United Kingdom, the politician responsible for climate and energy, Chris Huhne, has chosen this moment to say that it would be “crazy” not to prepare for a low-carbon future. The UK may be, controversially, positioning itself – along with certain other old member states – to insist on cuts to the forthcoming EU budget, cuts that would undoubtedly impact the most on CEE countries. A telling response from the CEE countries, to justify continuing the same level of EU funding beyond 2013, would surely be: we need the money to de-carbonise our economies, and we commit to doing so with big numbers for energy efficiency and renewables to be paid for via the EU funds.

4. BTC under fire for violating human rights obligations and pipeline integrity issues

The UK government ruled earlier this month that the BP-led Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) Company consortium is breaking international rules governing the human rights responsibilities of multinational companies in its operations on the controversial BTC oil pipeline. Environment and human rights groups in the UK, which filed an official complaint against BP eight years ago, say the ruling puts the oil multinational in breach of its loan agreements – including a multi-million pound loan backed by UK taxpayers.

5. Hunting for sustainability in Hungary

In February CEE Bankwatch Network and its Hungarian member group National Society of Conservationists were the co-hosts of a two-day conference in Budapest that tackled the pressing issues of water protection management and energy security. The proceedings, organised to coincide with Hungary’s presidency of the EU, took place in the “Hunting room” of the Hungarian parliament.

Among the speakers was the CEO of MAL Zrt., whose plant was responsible for the red sludge disaster in Hungary last autumn, who stated that the company has complied with and continues to comply with all the required regulation. Civil society speakers insisted that decision makers have the responsibility of eliminating activities that can bring about water pollution and urged them to use the EU presidency to push for more extensive, binding water protection plans.

Energy dependency dominated the second day of the conference, with fossil fuel consumption and the Nabucco gas pipeline among the main talking points.

Representatives from different departments of the Hungarian Ministry of National Development outlined to the participants the relation between the draft of the new Hungarian energy strategy and the country’s longer-term energy plans up to 2050. A representative of the NGO Crude Accountability described the problematic issues involved in western European countries relying on the eastern European and Caucasus region for their energy security – an acute, ongoing process with deep implications for European climate change and human rights agendas. Two panel discussions concluded the proceedings, one focusing on the destructive nature of fossil fuels and the other discussing the available options for reducing fossil fuel consumption.

Villagers living along BP’s flagship oil pipeline have struggled to hold the companies accountable for alleged human rights abuses associated with its development.

The ruling follows the Complaint lodged under the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises by six groups in April 2003. The UK government backed the pipeline in 2004 through its Export Credits Guarantee Department (ECGD). Given BP’s legally-binding commitment to ensure that the BTC project complies with the OECD Guidelines, the UK government ruling potentially places the company in breach of its contracts with the international financial institutions (IFIs) that backed the USD 4.2 billion project with taxpayers’ money in 2004. In addition to the UK’s export credit agency, these include the International Finance Corporation of the World Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and other European and US export credit agencies.

The ruling states that BP failed to investigate and respond to complaints from local people of intimidation by state security forces in Turkey guarding the pipeline. Local human rights defender Ferhat Kaya, for instance, has reported that he was detained and tortured by the paramilitary police for insisting on fair compensation. Villagers allege that they are routinely interrogated when they raise concerns over the pipeline.

The pipeline passes through an area of north-east Turkey with a substantial Kurdish minority who have been subject to state repression for decades. Since the pipeline’s inception over a decade ago, human rights campaigners in Turkey and the UK have highlighted the risk of local people, particularly Kurdish minorities, being intimidated by state security forces. The ruling finds that, despite widespread awareness of this “heightened risk intimidation”, BP failed adequately to respond to or investigate allegations of abuse that were brought to its attention.

The Complaint argued that such intimidation deterred local people from participating in BP’s consultations about the pipeline’s route and compensation negotiations for loss of land and livelihoods.

BP has consistently promoted the BTC pipeline as “world class” in its approach to human rights. According to its legally-binding commitment to comply with the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights (an international code of conduct for multinationals operating in the energy sector), BP is obliged to “consult regularly” with local communities about the impacts of pipeline security arrangements and should record and report credible allegations of abuse by security forces to the authorities.

The UK Government has now found that BP breached its undertaking and failed to adhere to the Voluntary Principles in the north-east region of Turkey by not responding adequately to allegations of intimidation and not investigating them.

The ruling sets a major precedent. In future, to comply with these corporate social responsibility guidelines, multinationals will have to take into account the human rights context in which they operate, including the risk of intimidation, when designing and implementing corporate grievance mechanisms. Such mechanisms need to be robust enough that people can report intimidation without fearing further reprisals.

The failure of BP to adhere to the OECD Guidelines and the Voluntary Principles, as required under the BTC project agreements, also raises major concerns over the due diligence undertaken by the IFIs before supporting the pipeline.

Nicholas Hildyard of The Corner House, one of the groups that brought the Complaint, commented: “The public funders knew about the intimidation, intimidation that is still going on, but failed to check whether BP had adequate procedures in place to address and remedy it. They ploughed ahead with the project for political reasons. Western governments appear to have been willing to sacrifice the human rights of those living along its route in order to grab the Caspian’s oil for the West.”

OPIC picks up pipeline defects

The Overseas Private Investment Corporation, a US government insurance agency and also a backer of the project, released a telling report into the BTC project in October last year – OPIC’s Office of Accountability had carried out a monitoring report into OPIC’s response to a previous compliance review of the project. The new report offers some revealing evidence about problems and oversights connected with the pipeline.

For example, “The contracts of the Independent Environmental Consultant and the Independent Engineer are such that neither of these third parties, that act on the lenders’ behalf, is reviewing water quality data collected in the region of Georgia that is of most concern to the Government, the Requesters, and the preparers of the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment for the pipeline.” This suggests that monitoring data covering for example the sensitive, water rich Borjomi region of Georgia, through which the BTC pipeline passes, is not subject to third party review.

The OPIC report describes several tests that have shown the pipeline wall to be weakened, with mention of excavation and repair of the pipeline in one section of the pipeline in Georgia having taken place. A controversial, untested pipeline joint sealant is being used in the pipeline, as campaigners and investigative journalists revealed seven years ago.

Along with a range of descriptions of certain technical details that do not inspire an excess of confidence, we learn also from the report that OPIC followed its site visit with a letter reminding BTC Company of its obligations “to comply with the applicable environmental and social policies and guidelines of the lenders, with the ESAP [Environmental and Social Action Plan], and with national law.”

Bankwatch coordinator Manana Kochladze, who for over a decade now has campaigned for environmental and social justice to be upheld during the construction and implementation of the BTC project, said: “There is more than a suggestion in all of this that BP is not complying with the environmental conditions, which places them in potential default of the contract with lenders. OPIC is to be praised for the rigour they are trying to bring to project monitoring. Unfortunately, though, it appears that they are having to try to whip BP into some responsible shape. It’s certainly curious that monitoring conducted by some of the other big international lenders such as the IFC and the EBRD tends to give the BTC project a clean bill of health.”

Wikileaks exposes major BP blowout on Azerbaijan gas platform

BP’s related operations in the Caspian Sea also caught the headlines in December when the Wikileaks website revealed the extent of a giant gas leak in September 2008 on a BP platform in Azerbaijan, which resulted in two fields being shut and output being cut by at least 500,000 barrels a day with production disrupted for months.

The leaked embassy cables detail that BP “has been exceptionally circumspect in disseminating information about the ACG gas leak, both to the public and to its ACG partners”. Another cable, written a few weeks after the blowout, describes Bill Schrader, BP’s then head of Azerbaijan, admitting that it was possible the company “would never know” the cause although it “is continuing to methodically investigate possible theories”.

The need for greater transparency and accountability in relation to BP’s Caspian operations, including the BTC pipeline, has undoubtedly never been greater.

6. Roads that rob us: no accountability for infrastructure development in Azerbaijan

by Rzayev Namik, The Oil Workers’ Rights Protection Public Union, NGO Baku

A road construction boom in Azerbaijan began in 2006 and is currently at its peak, with over a dozen projects now implemented, many involving loan investments from international financial institutions. However, questions are being asked about how to enhance both governmental and public control over the efficient use of these loan funds, particularly in the road construction sector.

Indeed, how justified is the need to attract foreign investment at interest if Azerbaijan enjoys a significant flow of funds from oil sales, which enables Azerbaijan’s government to increase the share of budget financing every year? After all, any loan must be returned with interest, which has knock-on effects on the welfare of ordinary people.

So why is this particular sector so attractive for foreign loans? It can perhaps be explained by the number of complaints received from people regarding the quality of the constructed roads. For example, the highway connecting the capital Baku with the western Shamakhi District, stretching for 124 kilometres long, was commissioned in November 2009 and has cost the country USD 200 million. Each kilometre of the road, therefore, has cost taxpayers a huge USD 1.62 million.

At the start-off phase of the project, the total project budget was USD 100 million, but this was subsequently doubled by the World Bank, although as efforts made by the public to get to the bottom of this sharp rise have revealed, no changes to the draft proposals have been made. Indeed the length and width of the road have remained the same, as well as the number of interchanges and bridges.

The astonishing thing is that no explanations for this kind of cost increase are given and the Azeri public is confronted with the fact that it will have to pay back the magically inflated, borrowed money over 50 years. It’s fair to say that it is impossible for the public to obtain information on what loan funds – like for this road or, for instance, for three sections of the Great Silk Road also under construction – are being spent on.

Missing procedures

According to standard Terms of Reference, when constructing strategic roads it is necessary to carry out a set of social and environmental procedures, in particular:

- Public consultations on the project,

- An environmental impact assessment of the road construction

Unfortunately, what we see happening in Azerbaijan’s road sector, even when there is international financial institution involvement, is that none of these mandatory operational procedures are being implemented during the construction of these roads.

Public monitoring reports by the Oil Workers’ Rights Protection Public Union (OWRP) have picked up evidence of poor quality road beds that fail to meet the category of the road classification; traffic interchanges constructed that fail to take into account traffic volume; and basic engineering design of roads that fails to meet the requirements of national Construction Directives and Rules.

These failings were raised in the spring of 2010, during the country visit to Azerbaijan of representatives of the International Monetary Fund. During meetings, NGOs repeatedly pit forward proposals for how to enhance public monitoring over the implementation of loan-financed projects.

What gives the public control?

The most important social control mechanism is transparency and systematic public information on how – and for what – borrowed funds are being spent. There has to be, too, observation of the environmental legislation of the Republic of Azerbaijan, transparency over how social and environmental compensatory measures are fulfilled, and compliance with the approved construction rules and standards. Public monitoring can very often help to resolve arising problems quickly, and of course prevent the deepening of social tension and conflicts.

Thus, public monitoring can be a mutually beneficial mechanism for the development of partnership between the government, the public, and all parties concerned. In addition, public control – if allowed to take place – can facilitate the fulfillment of all state obligations to the international financial institutions, and vice versa.

It goes without saying that the implementation of major infrastructure projects requires strict compliance with all regulations and safety rules. For this and the other reasons stated, OWRP is proposing the following methodology for adequate public control to take place in Azerbaijan:

- In coordination with governmental agencies, public control is to be carried out at all stages of construction, including: earthwork, welding, insulation operations, laying precast pipe joints, backfilling and land reclamation, as well as during activities aimed at protecting the environment, and addressing social issues and maintaining the appropriate local infrastructure based on the commissioning of social services by a relevant governmental agency;

- When carrying out public control without coordination with relevant entities, public opinion research among employees and local communities in the immediate vicinity of the construction site should be carried out. In such instances, mini marketing studies of the opinions of people from local communities may help identify possible deviations from the project brief.

For the public monitoring, a network of five civil society organisations (including OWRP) has been formed and it is expected that the network will be actively engaged in the monitoring.

In carrying out public control it is necessary to use reliable facts, and this requires gathering a lot of source material on the basis of which the credibility of the project feasibility study can be inspected. The main focus, while collecting primary environmental data on hydro-geological, tectonic and the engineering-geological conditions of the planned road construction corridor, should be placed on the environment impact assessment of road construction, as well as the social sector development. Often, under the pretext of poverty reduction, projects that contribute to the deepening of both environmental and economic problems are implemented.

The right to accurate information

Reliable data of course makes it possible to properly inform the public how economically rational is the implementation of one or other project, or if is it simply an excuse to raise another loan. It may happen that road construction would bring more negatives than positives. Public control facilitates the public hearing of local people during the project implementation and may prevent or mitigate the likely negative impacts of road construction on the environment and associated social, economic and other consequences.

The Republic of Azerbaijan has been a party to the Aarhus Convention since 1999 and, therefore, every citizen has the right to:

- obtain environmental information related to the proposed activity

- declare their interests and preferences

- express their opinions and give suggestions

- receive a response.

These rights should ensure the legal rights to a healthy natural environment, living environment and habitat, compensation for harm to health, and compensation for inconveniences caused by road construction and possible violation of standards and regulations.

In this way, public control allows every individual to obtain and disseminate accurate information about the proposed activity. Moreover, there is an opportunity to hear the opinion of local communities, make suggestions and comments, and exchange views on the proposed activity. All materials collected in the process of social control may be handed over to the competent authorities.

7. EU funds at the heart of yet another Czech political corruption scandal

The planned upgrade of Prague’s waste water treatment plant – a multi-billion Czech crown project that has also been seeking co-financing from the EU funds – may at first glance appear to be a rather mundane, if necessary, civic infrastructure project. Yet it has proven to be the source of a monumental political scandal that dominated the Czech headlines over the Christmas period, throwing up a distinctly foul-smelling mix of political intrigue, corruption and the continuing withering of public trust in the country’s elected representatives.

The scandal arose at the end of last year when it emerged that Libor Michalek, the director of the State Environmental Fund (an implementing agency for EU-funded environmental projects) had been secretly recording instructions, originating from Environment minister Pavel Drobil and delivered via his adviser Martin Knetig, allegedly urging Michalek to manipulate public orders at the Fund in order to financially benefit the Euro-sceptic ruling Civic Democratic Party (ODS) and to advance Drobil’s career.

These ‘manipulations’ included the project to upgrade Prague’s wastewater treatment plant, a project that has courted controversy for some years now. The plant upgrade costs have an official estimated price tag of EUR 640 million, although critics say that no more than EUR 20 million should be sufficient to complete the work, while fulfilling European Commission requirements. Nevertheless, as we now know, the plan emanating from Drobil’s office was to inflate the project’s budget by another EUR 120 million (on top, that is, of the EUR 640 million estimate) and to arrange a EUR 20 million kickback to the ODS coffers.

Following press revelations detailing Michalek’s covert recordings, the Environment minister Drobil first moved to dismiss Michalek, and then only after increasing political pressure resigned himself. The Fund director Michalek claimed that he had earlier informed both the Czech prime minister, Petr Nečas, as well as minister of the interior Radek John about these alarming goings-on.

Notwithstanding the fact that the man who reported high level corruption efforts was punished by losing his job, and has subsequently not been reinstated to his position even after a new minister of the environment (again from ODS) was appointed in the new year, the whole saga is highly illustrative of current political mores in the Czech Republic, where public budgets are under the control of different influential economic groups that are either linked to or directly present in the political sphere. At the same time, when it comes to prosecuting politically linked crimes, the Czech police and judicial authorities continue to play an abject role of powerless bystanders.

What has been striking in this case is not only the explicitness of the communications at the highest ministerial and State Environmental Fund level, but also the ensuing political reaction within the governing ODS party and from the prime minister himself. While Libor Michalek recorded the discussions in order to put together evidence about a planned crime, the dismissed minister Drobil had his knuckles rapped for managerial weakness – staggeringly, his party’s main concern was that he had strayed in appointing an unreliable person to the position of the Fund’s director. Needless to say, Czech president Vaclav Klaus, who still maintains intimate ties with the ODS party, has if anything defended what he believes to be Drobil’s innocence in the case – for the hardened climate sceptic Klaus, Drobil of course has re-established order in the Czech environment ministry following years of hijack by the green ideology.

That this case was linked to a project seeking EU co-financing – approximately half of the EUR 640 million costs would be covered by EU money – is also illuminating, demonstrating as it does how massive amounts of public resources are still very much vulnerable to illicit procurement practices. Yet the fact that as of the middle of the 2007-2013 financial period the Czech Republic had drawn only CZK 89 billion out of the total potential EU funds allocation of CZK 782 billion (11 percent) is perhaps an indication that the overseers of the funds in Brussels are alive to the prevalence of sharp practices surrounding the allocations of funds.

More depressing is the fact – and it comes as no surprise – that Czechs’ trust of political parties is now at critically low levels: a recent poll showed only 8 percent of the population to be broadly satisfied with the activities of the political parties. Regardless of the final level of EU funds’ allocations in the Czech for this budgetary period, the main priority has to be to work for changes in political thinking and goals, in order to banish the prevailing cynicism and to achieve outcomes that are beneficial for Czech society as a whole.

8. EU Funds on the line – road lobby attempts to derail sustainable transport development in Poland, Slovakia and the Czech Republic

Over EUR 1.5 billion of EU Funds designated for railway upgrading, as well as for the support of education, science, employment and regional development, is at risk of being reallocated for major new road build in Poland, Slovakia and the Czech Republic. CEE Bankwatch Network has in recent weeks been waging efforts in the three new member states and in Brussels to ensure that both EU sustainable transport priorities and the decision-making rules that govern the EU Funds are upheld.

The moves in Poland, announced by the country’s transport minister in January, are the most significant in terms of the sheer scale of EU Funds involved – the Polish government is seeking permission from the European Commission to shift PLN 4.8 billion (approximately EUR 1.2 billion) of EU cohesion funds from rail projects to major roads’ development.

However, according to a report last week in one of Poland’s leading daily newspapers, Rzeczpospolita, the first negotiation meeting between Polish vice-ministers and Commission officials failed to convince the Commission to grant the reallocation. An official response is not expected until the second half of this year at the earliest.

Bankwatch maintains that EU-financed railway upgrades in Poland are crucial as the national rail network is in a very poor state, so much so that the dilapidated infrastructure is hindering Polish rail’s competitiveness. Only 37 percent of the network is deemed to be in good condition, and on only 5 percent of tracks throughout the country can trains travel at the maximum 160 km per hour speed.

It shouldn’t be ignored, however, that railway upgrade projects financed from EU sources have been significantly delayed in Poland. By the end of 2010, only about 20 percent of the available funding had been contracted to specific projects. By comparison, the money for motorways and expressways in the TEN-T network within Poland has been almost completely assigned to projects (95 percent). This, therefore, has helped to raise the possibility of using the funding available for the railway sector by 2015 – when the spending under the current budget period has to end – instead for roads.

The arguments in favour of such a move have been made more keenly owing to the fact that implementing the railway upgrades is relatively complicated and time-consuming, even more than for new road building. Among the many reasons for the slow uptake of EU funds for rail, perhaps the most important are the low capacity and institutional problems of the company managing the rail infrastructure in Poland, PKP PLK. Reforms of this state-owned company have been neglected and national budget financing systematically cut in the last 20 years. At the same, though, protests against cutting Polish railways out of the EU funds have been gathering steam from a number of sources, including members of the Polish parliament, rail trade unions, and NGOs.

Przemek Kalinka, national coordinator for Bankwatch in Poland and a specialist in monitoring the EU’s structural and cohesion funds, commented: “The European Commission should not agree to this reallocation of funds. This would give the Polish government the wrong signal: you can neglect the railway sector and shift the money as you want, regardless of EU sustainable transport priorities, not to mention the allocations that were honestly brokered across the transport sectors at the beginning of the current budget period.”

Kalinka explains that any further development of roads in Poland via the EU funds, directly at the expense of boosting environmentally friendly transport modes (such as rail, urban, intermodal) will reinforce the trend of the last 20 years where car transport has been sharply increasing its share in both passenger and freight transport. In Poland, 92 percent of transport emissions originate from road transportation, while greenhouse gas emissions from transport more than doubled over the 17 year period between 1990 and 2007.

Short-changing the railways in the Czech Republic

While Czech national railways shares none of the same funds absorption problems as its Polish counterpart, nonetheless moves are afoot – sponsored by the Czech transport ministry – to shift CZK 10 billion (approximately EUR 411 million) of EU funds from agreed upon rail allocations to motorway projects. A request for approval from the European Commission has so far not been forthcoming.

Slovak NGOs alert to funds bypass for roads

Earlier this month, 26 Slovakian environmental and social NGOs formally appealed to their government and the EU institutions to put a stop to the reallocation of regional funds – a proposed EUR 350 million – from several operational programmes to road building. According to the groups, such a reallocation would be contradictory to both national legislation and EU funds decision-making rules. In addition, the Slovak Ministry of Transport hopes to reallocate EUR 250 million from railroad construction to roads and motorways, within the spending tranche for Slovak transport projects – thus EUR 600 million in total is at stake.

The authorities in Slovakia are intent on reallocating EU funds initially destined for the support of education, science, employment, regional development, the fight against social exclusion as well as rail development in favour of the construction of motorways, including certain investments that have long been mired in controversy.

According to the Slovakian NGOs, the planned reallocation represents a clumsy intervention into the whole system of structural funds in Slovakia in the current programming period, one which will affect the realisation of Cohesion policy priorities. Moreover, the reallocation was decided by the Slovakian government without any discussions with socio-economic partners, a direct violation of the partnership principle, one of the pillars of the Cohesion policy, as well as of the EU itself.

The NGOs, including Bankwatch member group Friends of the Earth – CEPA, also maintain that the planned reallocation in favour of highway construction contradicts the goals of the EU as set out in the Europe 2020 strategy – the strategy stresses the need to support the development of environmentally friendly transport modes with low carbon intensity, such as rail.

The most recent Slovak press reports suggest that the European Commission is far from ready to grant a green light to the Slovak government proposals, with details emerging that the country will have to implement its share of already allocated funds for motorways first before reallocations from other transport lines are to be considered.

Recent correspondence between Slovakia’s deputy prime minister Jan Figel and Johannes Hahn, European Commissioner for Regional Policy, also suggests that the Commission is prepared to take a firmer line on seeing through previously agreed joint commitments than perhaps the Slovak government was expecting.

Referring to proposed transfers of EU funding lines, Hahn wrote to Figel on February 17: “There is of course a need for a thorough consideration of transfers from programmes that are meant to contribute to important objectives of the EU.” The programmes in question, and those under threat from the proposed transfer to road projects, aim at supporting competitiveness, innovation and research as well as the furthering of the “information society” – all Europe 2020 objectives.

Commissioner Hahn spells things out further in the same letter: “In the case of such transfers, I would consider it important that the Slovak authorities commit to a reinforcement of the efforts to implement the remaining ERDF [European Regional Development Fund] resources in the programmes concerned. In addition, given the objectives that the EU has set itself concerning sustainable development, any proposal to increase the allocation for motorways should also be balanced by a commitment to continue investing in clean urban transport or other sustainable modes such as railways or intermodal centres.”

A quite specific Commission support, then, for sustainable transport and at the same time, behind the diplomatic language, a clear message for the Slovak government: get on with doing what was already agreed.

9. World Bank sponsored privatised pension pillar crumbling in Poland

by Gavin Rae, Warsaw

When Leszek Balcerowicz cries ‘No Pasaran’ you know that something is afoot. Yet this is precisely what the architect of the post-1989 shock-therapy reforms and the privatisation of the Polish pension system has recently been declaring in the face of the Polish government’s attempt to partially reform the country’s pensions.

The issue of how to provide for those in their old age has become a central issue for governments around the world. In the wake of the global financial crisis, many European governments have responded by introducing a wave of austerity measures, including attempts to raise the age of retirement. However, the crisis has also revealed how the privatisation of the pensions’ systems in some central and eastern European countries has in fact increased the fiscal burden on governments, whilst simultaneously decreasing the income that retirees will receive.

The blueprint for the private pension system evolved in Latin America, more precisely under the repressive dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet in Chile – the favoured administration of the Chicago Boys and the New Right. However, due to the unpopularity of the Pinochet regime, it was not until the mid-1990s that other countries began to emulate this model, as neoliberal governments were established in a number of Latin American countries and the World Bank began advocating a private pension scheme.

In 1994 the World Bank published a key report – ‘Averting the Old Age Crisis’ – that supported the establishment of a three-pillar pension system. Although this report stated that this could take a number of forms, the World Bank began to openly espouse pension reform based upon the Chilean model. The three pillars of this pension model are a publicly managed fund, a mandatory individual private fund and a voluntary private fund.

The advocates of this reform assumed that the rates of return in these individual private funds would be higher than in the public system and that it would provide an important freedom of choice to the individual. They also believed – following their ideological contours – that it would deliver a series of other benefits to the economy, such as increasing labour market incentives and reducing administration costs. Therefore, individuals would work later into life, as the more they pay into their own funds the more they would eventually reap. By 2002, ten countries had either partially or totally privatised their public pension system. In central and eastern Europe, where neoliberalism continued to exert significant influence, a number of countries – the Baltic States, Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia – followed suit.

Mass unemployment has been a feature of Polish capitalism, the jobless rate growing to over 14 percent by 1992 and only briefly dipping into single figures after Poland’s entry into the EU in 2004. With the introduction in 1990 of a very weak insurance system for the unemployed, many Poles responded by opting to retire – leading to a large rise in the number of pensioners and a surge in government pension expenditures. One of the major aims of the pension reform package, introduced by the right-wing coalition government in 1999, was therefore to institutionalise fiscal restraint and to encourage longer working lives through linking earnings to benefits. The government simultaneously ran a propaganda campaign showing future pensioners on exotic holidays wearing Hawaiian shirts, with the message being that individual pensions would be higher under this new private system.

However, the new reforms squeezed pensions in two ways. First, public pensions were no longer guaranteed to be 35 percent of the average wage and were indexed to price increases rather than wage growth. Second, by introducing a mandatory private fund, pensions were now at the mercy of the financial markets. The unspoken reality of the reforms was that future pensions were now not only going to be lower, but they would also be highly exposed to financial shocks.

The financial shockwaves that spread around the globe from autumn 2008 did indeed reveal the weaknesses of the Polish pension system. Almost immediately it became clear that the private pensions were going to be lower than people had been led to believe. In 2009, the first recipient of a mandatory private pension learnt that she would receive just ZŁ24 a month on top of her public pension. Admittedly, the woman in question had only been paying into the system for around ten years, but this nonetheless exposed how little these investments are actually worth. This was accompanied by Poland’s social insurance company (ZUS) sending, for the first time, projections of future pension levels to individuals paying into its scheme. People began to realise that their pensions would be even lower than those received presently by their parents – a sobering thought indeed.

At the same time, the financial crisis worsened Poland’s public finances, with the budget deficit exceeding seven percent of GDP in 2009 and public debt edging towards the government’s self-imposed limit of 55 percent. When the Polish pension system was reformed it was established that those aged 50+ in 1999 would remain within the old system. This meant that ZUS was required to continue paying these pensions, while 7.3 percent of total gross salaries was transferred to the private pension funds. This has added up to a total of ZŁ162bn since the beginning of the reform, equivalent to 11.4 percent of Poland’s GDP in 2010. This transfer has been one of the contributory factors to the growth of public debt, which has risen by 13 percent since the formation of the private pension funds.

The transfer of public money to private companies has to be further questioned when the level of profit that these companies have drawn from the public purse is considered. Professor Leon Podkaminer – from the Vienna-based Institute of International Economic Studies – estimates that in 2009 the private pension companies in Poland made a clear profit of around USD 766 million, from an investment of around USD 3 billion (ie, with a profit rate of 25 percent). While the privatisation of the pension scheme was supposed to extend individual choice and freedom, it has become clear that it has become a mandatory scheme for passing public money into the hands of private financial companies.

With public debt continuing to rise, the Polish government has realised that the present pension system could not be maintained. It therefore announced, in January this year, that it would be cutting the amount that is paid to the private pension funds, from 7.3 percent to 2.3 percent, with the clawed-back five percent to be used to cover the costs of present public pensions. However, the government has also stated that it will be seeking to increase the payments to the private pension companies to 3.8 percent by 2017.

Inevitably this has led to a barrage of criticism against the centre-right government, particularly from those who helped to privatise the system and who had previously considered the government to be political allies. The crux of their arguments has been that the government is reaching into the pockets of ordinary citizens in order to cover their own deficits. They argue instead that the government should seek more substantive reforms to reduce government expenditures.

As an alternative, Leszek Balcerowicz for one has proposed that the government introduces reforms such as raising the retirement age, taking away early retirement privileges, reducing funeral subsidies, stalling the planned lengthening of maternity leave, abolishing the one-off payment for newly born children and getting rid of VAT relief for hoteliers and the building industry. He also proposes that the government speeds up the privatisation process, in order to boost the government’s coffers. In fact one of the major criticisms, made by the original architects of the privatisation of Polish pensions, is that successive governments both failed to privatise enough and did not use these funds to cover over the hole left by payments to the private pension funds. However, the conception that it is either desirable or possible to continue selling state economic assets in order to cover the hole left by payments to private pension companies, is in itself highly dubious.

The move away, in recent times, from private pensions has not been restricted to Poland. Already governments in Latin America (including Chile, Argentina and Bolivia) have partly or fully nationalised their pension systems in recent years. In central and eastern Europe over the past 12 months Lithuania has reduced contributions to its private funds, Estonia has declared that it would freeze pension fund contributions, and in Bulgaria 20 percent of private vocational pension funds will put their assets under state control by 2014.

In Hungary, most notably, the current government announced at the end of last year that individuals would have to decide whether they wanted to invest in the state or the private pension system. Up to now, around 3 million workers in Hungary have been investing some of their pension contributions in private schemes and those that choose to remain with the private pension system will lose the right to draw their future state pension. By the February 1 deadline, 100,000 (or three percent) of Hungarian pension subscribers opted to stay in the private system. It is estimated that this de-facto nationalisation of the Hungarian private pension schemes will be worth USD 14.6 billion, a sum that the Hungarian government views as vital for working down the country’s national debt. The danger, however, exists that the Hungarian government will use these funds simply to cover its own public finance problems and meet the demands to cut its budget deficit laid down by the EU. Any return to a public pension system in Hungary should be combined with a commitment to use these accumulated funds to help valorise future pensions.

Sat alongside such reforms elsewhere, the recent decision of the Polish government can be seen to be rather modest. Moreover, a pressing question remains: if the private pension system has been such an obvious failure, why not just abolish it entirely?

That being said, and despite its coming under external political pressure, it is worth bearing in mind that the current Polish government happens to include many people with a personal interest in defending the private pension system. As has been documented recently in the Polish media, nine out of the 11 members of the present government’s Economic Council have worked at some time for a private pension fund. The Economic Council – created by Donald Tusk last year – is comprised of economists and businessmen who provide the prime minister with advice on economic issues and help to plan the government’s economic strategy. Therefore, while the Polish government may have made an important first step towards moving away from the private pension system, a large lobby group surrounds these pension companies and exerts a significant influence in national politics and the media.

If it’s of any reassurance to Leszek Balcerowicz, such interests are determined that any further move to abolish the private pension system in Poland ‘shall not pass’. The outlook for Poles working towards a pension, then, appears mixed, while for purveyors of Hawaiian shirts the main target market appears to be restricted for the time being to the top echelons of Poland’s private pension fund companies.

Gavin Rae is a sociologist at Kozminski University in Warsaw. He is author of the book ‘Poland’s Return to Capitalism – From the Socialist Bloc to the European Union’, and runs the blog ‘Beyond the Transition’

10. Austerity is the mother of rising dissension in Romania

In 2009, Romania accepted a EUR 20 billion loan package from the IMF, the World Bank and the European Commission, aimed primarily at stabilising the national currency and banking system in the context of the global financial crisis. The loan was conditioned by a package of austerity measures intended to limit the country’s budget deficit to 6.8 percent of GDP in 2010. The Romanian government argued that without the IMF loan Romania’s indebtedness could rise to over 60 percent of GDP by 2013. The austerity package involved a cut of 25 percent in the salaries of all state employees as well as significant cuts in the public sector, among other measures. Victoria Stoiciu of Critic Atac discusses the scale and effects of the job cuts that have resulted from the IMF’s fiscal medicine for Romania.

In 2010 a full-blown attack on the public sector took place across Europe: in the EU, 13 percent of jobs lost because of the economic crisis fell in the public administration sector. In Romania, too, 2010 was the year in which the public sector was under siege, though unlike in other European countries, the social battle in Romania was not noticeably intense as in some other countries. Nevertheless, its effects have been immense.

According to data from Eurofound, the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions and an official EU body, in 2010 Romania was the European leader in public sector job restructuring: 78,700 public jobs were axed, representing 21 percent of jobs from all economic sectors that disappeared across the EU as a whole. In second place behind Romania was the UK, with job cuts from all sectors there accounting for 20.83 percent of the EU total. Importantly, though, while UK job cuts have been deep, a considerable number of new jobs have also been created in the UK economy – 15.52 percent of the new jobs created last year in the EU. In Romania, however, the gap between cut and newly created jobs is much wider, with new jobs in Romania representing only 6.28 percent of the European total.

For the bulk of the remaining EU countries, the differentials between cut and newly created jobs were virtually non-existent, and in some countries the number of new jobs created outweighed job cuts. In Ireland, one of the countries most severely affected by the economic crisis, the number of new jobs was double that of cut jobs, while in Slovakia and Sweden new jobs outpaced job cuts by a factor of three.

The vast majority of public sector job cuts in Romania (60,610) fell in the public administration sector. Romania ranks second behind France in the EU in the total number of job cuts in public administration since the beginning of the economic crisis.

The purpose of these cuts, as outlined repeatedly by Romanian officials, has been to decrease the number of state employees in order to enact public administration reforms, while at the same time reducing the budget deficit. The effectiveness of such an approach to reform remains questionable since neither personnel cuts nor salary cuts are any guarantee of reform in itself – some managemant consultants do argue, in fact, that the main obstacle to reform is not large numbers of employees, but rather the quality and productivity of their labour.

In Romania, the public has become very familiar with the figure of the annoying bureaucrat looking arrogantly at people on the other side of the counter, as if the public is supposed to serve him and not vice-versa. But the solution to this problem is not cutting jobs. Numbers only affect the costs, not the quality, of job performance. Without the necessary changes in working culture, the potential for even worse service will indeed surely rise, with those remaining in public administration having to contend with reduced pay and fewer staff having to carry out more work.

Most tellingly, the economic and budgetary impact of these job cuts in Romania has been virtually zero. The achieved savings on public sector salaries have not helped to significantly reduce state expenditure.

For January-November 2010, according to the National Statistics Institute, salary costs from the state budget were 12.679 bn lei as opposed to 12.701 bn lei in the same period in 2009 – a virtually non-existent reduction, then, and this in spite of both heavy job cuts and salary cuts of 25 percent. In the consolidated budget (which also includes local budgets), savings were more significant, with expenses at this level decreasing by 8.5 percent. Nevertheless, even these savings can be viewed as relatively modest next to the hefty reductions in both job numbers and pay levels that have delivered them.

Leap of defiance

On December 23 last year, during a no-confidence vote on the present government, Adrian Sobaru, an electrician for TVR, Romania’s national television channel, jumped from the balcony of the Romanian parliament.

Before he jumped, Sobaru yelled out to the Romanian parliamentarians below, “You have killed our future!” and “You have taken the bread away from our children’s mouths!”

Forty-three year old Sobaru is the father of two children, one of whom suffers from autism and requires specialised assistance. His parents receive a carer allowance (the equivalent of 150 euros per month) from the Romanian state, but this was cut by 15 percent as a part of the government’s austerity plan agreed with the IMF, which included 15 percent cuts in most forms of social assistance.

Sobaru, who has not been diagnosed with any serious psychiatric condition, survived the jump and has declared since that his act was a political statement against the Romanian government and its austerity drive.

His actions postponed the vote of no-confidence, which took place last week with the coalition government surviving. The proceedings were marked by 10,000 demonstrators gathered outside the Romanian parliament. The demonstration was organised to protest primarily against the reform of the labour law that will make it easier to fire people and to make employees work longer hours.

The explanation for such low savings stems from a series of factors but, since no official studies and statistics exist yet, a few potential interpretations can be offered at this stage.

A first possible explanation was offered by Finance Minister Gheorghe Gherghina last year. According to Gherghina, the 25 percent cut was applied to salary expenses, which are lumped together with all personnel expenses in the state budget: since other expenses associated with personnel have not been cut, this diminishes the impact of salary cuts on the overall budget. Another possible explanation could be that salary cuts were only applied in the second half of 2010 and, taking that into consideration, this reduces the overall volume of savings. Finally, a third hypothesis is that among the cut jobs, many of these existed “on paper only”, hence they involved no expenses for the budget.

Many Romanian experts and journalists have indeed taken it as read that numerous such “paper-only” jobs existed. However, in reality, there are no precise numbers for this phenomenon and it is entirely possible that, rather than it being a widespread phenomenon, it is an example of a few cases being blown out of proportion by the media.

What is known is that state salaries in Romania are to be increased in 2011 by 15 percent, that is 15 percent of the 2010 post-cut level. The real increase, though, is actually of an order of 1.4 percent, given the 5.4 percent inflation rate as well as the fact that, in 2011, the traditional ’13th salary’ and holiday bonus will no longer be granted.

Romania has made some of the biggest sacrifices in Europe, but with the least impact in the union. We are the champions of Europe in terms of the harshness of austerity measures, but that is all we can boast about. What have we achieved? No savings for the budget, no increased productivity, no reform.

Time and again, Romania seems to insist on making human sacrifices in order to be reborn as a state. Time and again, a new social category is sacrificed – yet these human sacrifices never seem to pay off.

Meanwhile, a new follow-up deal from the IMF, World Bank and the EU, to come into effect in May this year after the existing arrangement expires, is in the works for Romania. Where will the hammer blow of austerity strike hardest next, and for whose benefit?

A version of this article first appeared in the online magazine of Critic Atac

11. Why the new EIB tax haven policy will not be effective

by Antonio Tricarico, CRBM and Counter Balance

Since the outbreak of the financial crisis in autumn 2008, the fight against tax havens has been a hot issue, and growing direct street level protests against major corporations and their deft use of these secrecy jurisdictions suggests that things are only getting hotter. Because in spite of commitments taken by different world leaders and the G-20 countries regarding tax havens, the policies put in place have proved to be ineffective. This looks likely to be the case for the recently reviewed tax haven policy of the European Investment Bank (EIB). Although the EIB’s policy goes further than those of other international financial institutions (IFIs), it will still do little to prevent European public money reaching tax havens.

The OECD club of rich countries has a dominant position in setting economic rules, on international tax in particular, and the widely hailed ‘moves’ that we have seen against tax havens since 2008 have come with an OECD stamp attached. But effectively, the OECD’s policy on tax havens reflects the interests of its members, many of which are tax havens in their own right. In April 2009 there was a G-20 statement that the ‘era of bank secrecy is over’, and this mandated the OECD to start cracking down on it, accompanied by a lot of media fanfare.

Yet, as Nicholas Shaxson of the Tax Justice Network, and author of the recently published bestseller Treasure Islands: Tax havens and the men who stole the world, points out: “If you actually look at the specifics of what the OECD has done since then it looks like a whitewash. There is no other word for it. There has not been the change that is required.”

It is within this context that the EIB has recently reviewed its policy on non-cooperative jurisdictions, more commonly known as tax havens or secrecy jurisdictions. Although the EIB is one of the few IFIs to have at least adopted a comprehensive public policy on tax havens, will this allow it to curb illicit flows and the abuse of tax havens by European corporations that benefit from EIB public loan support?

Betraying a highly ideological approach, and loaded as always in favour of corporate rights over public and taxpayer interest, the EIB has left several loopholes in its new policy. Apart from the reference to the toothless international lists of countries regarded as tax havens (that OECD problem noted above), the main problem lies in the wide number of exemptions granted to European business operating via tax havens. In particular the bank would still accept the usual argumentation of corporations around the need to operate via tax havens because of the inadequate legal framework and investment climate in many developing countries where projects are implemented, and consequently about the need to avoid burdensome double taxation.

This is clearly an approach biased in favour of investors’ rights which fails to consider that some provisions less friendly to investors could be highly suitable for local governments and populations, and their development strategies. However the EIB policy goes beyond these arguments usually used by corporations and accepted by public financiers. The EIB will permit corporations operating in a specific country to register in a different country which is a tax haven or secrecy jurisdiction just because there might be “other tax burdens that make the structure uneconomical”. Rather than a comprehensive tax policy this in fact reads like a bad joke!

Of even more concern is that the EIB policy does not exclude the possibility to support a financial intermediary incorporated in a tax haven or secrecy jurisdiction even if this bank or private financial institution , such as a private equity vehicle, operates in sectors related to the local economy of that country. Yet how can the EIB ever assess what is what if money is fungible and the same intermediary can engage in proprietary trading or shift the money elsewhere in a highly liberalised global capital and financial market?

The widespread use by the EIB of financial intermediaries and private equity funds poses a major threat to accountability at the bank, particularly in its lending outside of the EU where these entities are the destination for up to almost 40 per cent of its entire portfolio outside of the EU. As documented by recent Counter Balance research, all 12 private equity funds in which the EIB invested in Sub Saharan Africa between 2007 and 2009 were registered in well-known tax havens. Two of these indeed were in Luxembourg where the EIB itelf is based. As Nicholas Shaxson notes: “Luxembourg is a great dark horse of the offshore world – it is absolutely massive.”

The development implications of tax havens, of course, are hugely troubling. At the beginning of this year the Washington-based organisation Global Financial Integrity produced some startling new research. They asked a former IMF senior economist to crunch the numbers on illicit financial flows out of developing countries, and their latest analysis is that in 2008 USD 1.2 trillion – trillion, not billion – leaked as illicit flows out of developing countries. If we compare the USD 100+ billion of foreign aid going to developing countries, then this translates to one dollar going in as aid and ten dollars going out under the table. This is the bigger picture that the likes of the EIB and other IFIs are, unfortunately, only adding to with their lax policies.

What the EIB should be doing instead is simply limiting its partners to entities – whether private banks or equity funds – that are incorporated in the same countries as the ultimate beneficiaries, and then imposing fully transparent and stringent standards on them for the projects they support. While this principle should make perfect sense after the financial crisis, it is not being reflected in today’s practices between the EIB and the “trusted and experienced” financial partners it chooses. Moreover, information about the final beneficiaries is still so badly lacking that it makes it impossible to assess the environmental and development impacts of these projects, never mind the potential for tax abuse.

Since the European Parliament has recently called for significant improvements in the new EIB policy on non-cooperative jurisdictons through votes on both the 2009 EIB Annual Report and, more importantly, the new external lending mandate of the bank, MEPs have still an important, direct role in preventing public money ending up in tax havens by convincing EU member states to agree to these requests.