Originally posted on the Open Spending blog to coincide with a journalist community hangout where our EIB campaign coordinator Anna Roggenbuck presented her experience with the EIB’s data.

UPDATE (July 15, 2013): The EIB sent comments and clarifications to the original blog post from June 13 based on which the text has been updated. We include explanatory notes where revisions have been made. A detailed point-by-point exchange between Bankwatch and the EIB that includes a number of additional arguments can be downloaded as pfd.

How to understand data from the EIB – what does the data tell us?

For each project the EIB is considering to finance, it publishes on its website basic data including a description of the project, its location, the amount of EIB financing, in most cases the loan beneficiary and where relevant environmental impact assessments.

The data has its limitations: Machine-readable data is available on the website but it is not reliable because it significantly differs from the more detailed databases provided on request (see below). Furthermore, the aggregation of loan volumes can only be made at a sectoral level, pre-empting the possibility to examine different categories within the energy sector (energy efficiency, coal, gas and so forth.).

More detailed and accurate datasets for individual industry sectors are available on request, though not for all industry sectors (no transport database for instance) and you’ll have to wait up to one month for the file.

[In reaction to the EIB’s comments, we revised the original statement that “no machine-readable data is readily available, and it is not possible to aggregate loan volumes”. The EIB also pointed out that Bankwatch had received a number of databases within a few days. This, however, is not a general practice and when planning to examine EIB data, one has to be at least prepared for a longer waiting time.]

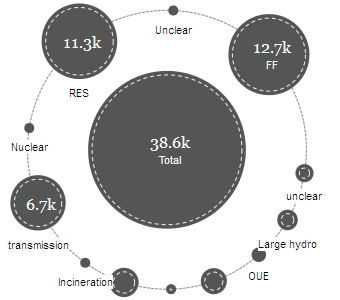

With these files you can relatively quickly aggregate and examine EIB lending in a certain country or region like old or new Member States and for different years. Slightly more complex, but still very much possible, is collecting data for sub-sectors (e.g. renewable energy). This is particularly useful if comparing for instance energy efficiency lending in the old Member States of the western EU versus the new Member States, where the potential of and need for energy efficiency measures is much higher. (Click on the “EE” circle (bottom-right) in the visualisation below to see more.)

At the same time, the data provided by the EIB is relatively sparse, and the files notably do not include the names of loan beneficiaries, which would allow assessing whether any companies receive particularly extensive EIB support and in which countries these are based.

Another problem is how the EIB categorises projects. Even though the bank uses an official Eurostat classification system (NACE), inconsistencies and unclear attributions create a much rosier picture about the bank’s lending. (See more details for the energy sector lending below.) Note that for a more critical assessment or investigation one needs to consult additional materials like project summaries, EIB project assessment reports (only available on request), or a project promoter’s website.

Why is it important to analyse the EIB’s classifications? The EIB energy lending as an example

The EIB boldly states that it is a leading institution in the fight against climate change. While the bank does lend significant amounts for renewable energy projects, it also finances a large number of climate-damaging projects.

What the EIB categorises as clean energy is often not clear. This is especially the case when portions of a particular loan are attributed to different, often conflicting EU priorities like financing for renewable energy and energy efficiency on the one hand and security of energy supply (to EU countries) and trans-European energy networks like gas or oil pipelines on the other hand.

By assessing each project individually, we found the following underlying trends in the EIB’s overstated green energy lending:

1. Unclear classifications

Quite a number of projects in the EIB database we simply removed because they did not seem to be related to energy, let alone renewable energy. For example all energy-related expenditures for the large-scale waste incineration plant Termovalorizzatore Torino were assigned to renewable energy. Since we argue that waste is not a “renewable” energy source, we excluded the project from our numbers. [*]

[In its comments, the EIB explained that the Poland Forestry and Environment project, which we had earlier used as an example here, contained an element of energy production from biomass. The information, however, can only indirectly be found in a 400 page pdf file available on the website of the Polish Ministry for Agriculture and Rural Development. In any case, the point we are trying to make here can be illustrated by a number of examples, which is why we replaced the one from Poland.]

2. Very broad strokes

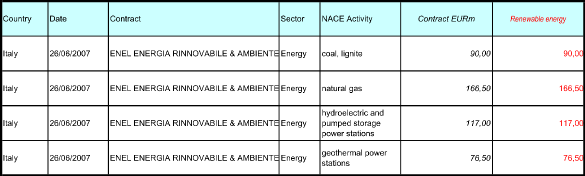

In some cases, financing that clearly did not go to renewable energy sources was nonetheless added to the renewables figure, even though renewables was just part of that loan. In case of a project with the Italian power company ENEL the EIB assigned the loan to “Renewable energy” even though more than 50% of the total loan of 450 million Euro was aiming at fossil fuels. (See the excerpt from the EIB’s database below. Irrelevant columns were deleted to reduce space.)

[In its comments to the blog post, the EIB explained that the classification of the project was a mistake in the database we received and that “this mistake was subsequently corrected and never taken into consideration in the Bank’s public data regarding its energy lending”.]

3. Compartmentalisation

Somewhat in contrast to point two, the EIB in many cases focuses too narrowly on the specific activity they finance rather than taking the impact of a project as a whole into account.

For example loans over (approximately) 200 million euros in 2009 for the construction of a new gas power plant in Portugal are considered energy efficiency (and thus boost the bank’s ‘green energy lending’) even though the project lead to additional capacity to burn fossil fuels and thus emit CO2.

[In its comments, the EIB correctly pointed out that the original example (the Karlsruhe power plant) was not classified as energy efficiency in the database. The point we make nonetheless remains valid and is illustrated by another example, since we maintain that efficiency gains per energy unit do not justify a classification under energy efficiency when the project leads to an overall increase in CO2 emissions.]

This is especially problematic in the case of greenfield power plants in developing or transition countries that often have a significant potential to increase energy efficiency. EIB money that could be used for measures to decrease energy loss and consumption, has instead financed new and more efficient (or ‘less inefficient’) fossil fuel fired power plants to address growing energy demand.

What further questions can we ask?

While the EIB’s 2011 energy figures have improved over previous years, the share of fossil fuels is variable when considered over a longer period of time. It will be interesting to see whether the positive trend from 2011 continues.

Up to 30 percent of EIB financing is offered as ‘global loans’ to intermediary institutions like commercial banks and different investment funds. Details for such activities are almost never available due to confidentiality provisions by the financial institution. A more in-depth investigation into these loans and the financial intermediaries could offer insightful information on how climate-friendly the EIB’s global loans are.

[*] Confronted with our criticism of its classifications, the EIB argued that Bankwatch’s analysis was misleading as it lowered the EIB’s support for renewable energy (by not considering large hydro and waste-to-energy projects) and to energy efficiency projects (by neglecting efficiency gains of new co-generation projects). Yet, since Bankwatch’s methodology focuses on a sustainability objective it takes the wider impacts of projects into account, like biodiversity impacts of big dams or the climate impact of new, greenfield fossil fuel power stations (even if they are considered more efficient than old ones, they are still new fossil fuel plants). The EIB rightly stated that Bankwatch’s methodology was not in line with standard EU methodology, but we made our methodology transparent and explained and justified our choices.

Never miss an update

We expose the risks of international public finance and bring critical updates from the ground – straight to your inbox.

Institution: EIB

Theme: Energy & climate

Tags: EIB | climate | data | energpolicy | energy | portfolio | sustainability