30 years strong: Championing sustainable development in central and eastern Europe

Since our founding in 1995, Bankwatch has been at the forefront of holding international financial institutions and governments accountable. We’ve challenged projects that threaten our environment and communities, worked tirelessly to promote transparency and public participation in decision-making, and played a key role in many environmental victories over the last 30 years.

None of these achievements would have been possible without the support of our dedicated members, partners and supporters. Join us in celebrating this milestone and help us continue our vital work for another 30 years and beyond.

From grassroots activism to fighting Goliath

Bankwatch’s 30-year quest for just and sustainable public finance

From grassroots defiance to a force for accountability, Bankwatch’s story begins long before its founding in 1995. Amid collapsing regimes, our network channelled the energy of civil resistance into a brave new experiment in public oversight and transparency.

Challenging powerful institutions like the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the European Investment Bank, and the World Bank, Bankwatch emerged as a reliable and determined counterweight to unchecked development.

This is the story of how a modest gathering of like-minded activists became an unstoppable movement for change – and why its mission remains more urgent than ever. For people and the planet!

30 years of Bankwatch: Reflecting on the past, present and future

In this anniversary episode, we celebrate 30 years of Bankwatch – a network founded in 1995 to push for public investments that truly benefit people and the environment in central and eastern Europe.

Fidanka Bacheva-McGrath, Mark Martin and Petr Hlobil look back at the early days and what inspired them to become Bankwatchers, the challenges they’ve faced and the impact the network has had over the decades. They also explore today’s pressing issues, from shrinking civic space to the need for sustainable and inclusive solutions.

Tune in to hear their reflections on Bankwatch’s journey to date, the lessons they’ve learned, and their hopes for the future.

OUR IMPACT

The origins of Bankwatch can be traced back to a conference organised by the German environmental organisation Euronatur in Stuttgart in April 1994, entitled ‘The World Bank: A Chance for the Environment in Europe?’

Later that year, in October, the World Bank convened for its annual general meeting in Madrid, where it also marked its 50th anniversary. It was there that our members met and began discussions about establishing Bankwatch.

The next step in the planning process was a meeting held in Brno in December, organised by the Czech environmental organisation Hnutí Duha. At this meeting, a formal decision was made to start developing a regional network.

In March 1995, the first meeting to discuss funding opportunities for Bankwatch was held in the Czech town of Ivančice. It took place in a local preschool, with participants sleeping in a large shared room. The informal, family-like atmosphere provided a productive environment for our early discussions on strategic planning.

In April, we gathered in Hungary for a training session for non-governmental organisations. After receiving financial support from our initial funders – the Rockefeller Brothers Fund and the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation – a meeting was held in Krakow in June, where the name of our organisation was agreed upon: the Central and Eastern European Bankwatch Network.

It was also decided that the Krakow headquarters of the Polish Ecological Club–Friends of the Earth Poland would serve as Bankwatch’s base, remaining so until 1998.

In October, the World Bank Annual General Meeting took place in Washington, D.C., where Bankwatch members were accredited for the first time as official non-governmental organisation delegates. Since then, Bankwatch has been represented at every World Bank Annual General Meeting.

That year also saw the first United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Conference of the Parties – COP1 – held in Berlin.

In January, during a meeting in Kaunas, Lithuania, the idea was proposed that Bankwatch should become an independent entity, rather than continue being hosted by Friends of the Earth Poland.

In April, at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) Annual Meeting in Sofia, Bankwatch made its first prominent appearance as a player at an international banking conference. The event also marked the first face-to-face meeting between Bankwatch and the EBRD President.

Later in the year, the EBRD adopted its Environmental Procedures, which established key measures such as environmental appraisals for all projects along with principles for public consultations. Bankwatch also became actively involved in the EBRD’s controversial K2–R4 project aimed at constructing two nuclear reactors in Ukraine.

In June, we held a meeting in the Polish village of Osieczany – a gathering that played a key role in shifting Bankwatch’s strategic focus. Initially centred on transport projects, the network began to prioritise energy issues.

September marked the first face-to-face meeting with the Vice-President of the European Investment Bank (EIB) in Luxembourg. That same month, the first Bankwatch email list was also created.

In 1997, the European Union (EU) began to prioritise climate change as a core environmental issue, building on the publication of the EU’s Green Paper the previous year, which introduced concepts for a future energy policy.

In January, an internal meeting was held in the Hungarian city of Göd. The primary focus of the meeting was to launch a campaign against the completion of the K2 –R4 project in Ukraine.

As the organisation grew, questions about the role of the network inevitably became a central theme. A key discussion revolved around whether Bankwatch should operate as a service-oriented organisation or as one focused on direct action. This question was largely answered through hands-on experience, as our network evolved into a multifunctional organisation providing services, information, and training to other groups, while also spearheading its own campaigns.

In May, during the EBRD Annual Meeting in London, Bankwatch’s top priority was to raise concerns about the K2–R4 project. Later in June, at another internal meeting held in the Polish town of Ustroń, the debate continued over the role Bankwatch should play – should the focus be more on campaigning or on policy-making?

By the end of year, the decision was made to organise a series of roundtable discussions at the national level, focusing on the EIB. The first of these events took place in Brussels, with the participation of policymakers, non-governmental organisations, the press, and academics. These roundtables proved to be a valuable tool in raising awareness of EIB policies, with many more held in other countries over the following years.

The year also marked a major landmark for the network with the publication of our first report – ‘Blueprints for sustainable transportation in central and eastern Europe’.

To round off the year, the Kyoto Protocol was adopted in December, with the EU taking a leading role in advocating for legally binding emissions targets.

In January, during a meeting in the Slovakian city of Trenčín, Bankwatch reached a key milestone in its development: the decision to become an independent legal entity. After an initially unsuccessful attempt to register the organisation in Poland, attention turned to the Czech Republic, where registration was successfully completed in November.

In March, Bankwatch launched its first website, hosted on a server at Tartu University in Estonia, a significant step towards increasing the organisation’s visibility and outreach.

In April, a meeting of the Stability Pact for South Eastern Europe was held in Bankya, Bulgaria. The aim was to bring together civil society organisations from across the Balkans and explore the creation of a network of south-eastern European non-governmental organisations.

The year also saw the launch of Bankwatch’s campaign against the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan oil pipeline, a major infrastructure project with serious environmental and social implications.

In May, the EBRD held its Annual Meeting in Kyiv. Participation by local non-governmental organisations was heavily restricted, prompting Bankwatch to organise a parallel reception outside the official venue. This event provided an alternative space for dialogue and was attended by both EBRD representatives and local activists.

In June, the Aarhus Convention was signed, establishing a legal guarantee for public access to environmental information, participation in decision-making processes, and access to justice in environmental matters.

By 1999, the EU was actively taking steps toward addressing climate change and reducing emissions. While the formal launch of the European Climate Change Programme occurred in 2000 as the EU’s central instrument for this purpose and to ensure compliance with Kyoto targets, the groundwork and policy discussions were well underway.

The year was also notable for the release of our first report highlighting the secretive nature of the EIB. This publication marked the beginning of a long and successful campaign for greater transparency and public oversight of this major public financial institution.

In March, a significant meeting was held in the Romanian spa town of Băile Herculane, which saw the relationship between Friends of the Earth Europe and Bankwatch become more formal, reflecting the fact that approximately half of Bankwatch’s member groups were also affiliated with Friends of the Earth.

In April, the EBRD Annual Meeting took place in London, where Bankwatch representatives held meetings with the EBRD President and Vice-President. Despite their support for the K2–R4 project, these discussions were crucial for raising our concerns about the EBRD’s accessibility to the public and its information disclosure policies and practices.

Around this time, Bankwatch also launched the first issues of Bankwatch Mail. Topics covered included critiques of the EBRD’s strategic direction, the rush for Caspian oil, as well as environmental issues surrounding the Kumtor gold mine, the K2–R4 nuclear project, and the Nuclear Safety Account.

In March and April, Bankwatch took on the role of secretariat for the World Bank’s Europe and Central Asia non-governmental organisation assembly, held in Vilnius. Our responsibilities included promoting the event among civil society groups across the region, facilitating the gathering itself, and acting as a liaison between the participating organisations and the World Bank.

In May, Bankwatch organised a training session in Baku for non-governmental organisations from Azerbaijan and Georgia, with a focus on strengthening regional capacity and campaign coordination.

Ahead of the EBRD’s Annual Meeting in Riga, also in May, Bankwatch undertook a lobbying tour across several key European countries, including Germany, Sweden, Norway, and France, targeting decision makers in an effort to influence outcomes related to the controversial K2–R4 nuclear project.

Immediately following the Annual Meeting, we held another internal meeting in Tartu, providing an opportunity for reflection and strategic planning.

Later in the year, in September, the World Bank and International Monetary Fund held their joint meetings in Prague. On this occasion, the President of the World Bank announced a review of the institution’s policies on fossil-fuel financing – an important development for our climate-focused advocacy efforts.

In March, Bankwatch held a regional meeting in Lviv, Ukraine, to address the need for internal reforms following a period of steady growth.

That year, the EBRD celebrated its tenth anniversary. Bankwatch marked the occasion with the publication of ‘A Decade of Misinformation and Secrecy’, a critical review of the EBRD’s policies and transparency record.

In June, a World Bank-focused training was held in Belarus and, in July, Bankwatch participated in international climate negotiations at the Conference of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol in Bonn.

In October, a strategy meeting was held in Łopuszna, Poland, followed by a training session in Romania in November. Bankwatch also launched several new tools, including a training CD, a citizens’ guide to the EBRD, and an updated website to support public engagement.

In April, the EU adopted its first renewable energy action plan to boost the development and market share of renewable energy. That same month, Bankwatch held a strategy meeting in Birštonas, Lithuania, focused on the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline, engaging in a detailed discussion on how to approach the case.

The EBRD Annual Meeting in Bucharest was the most successful of all attended, with the EBRD showing a greater openness to Bankwatch’s demands.

In June, Bankwatch played an active role in the World Bank’s Europe and Central Asia non-governmental organisation assembly in Belgrade. Additionally, thanks in part to Bankwatch’s efforts, the World Bank cancelled its loan for the controversial Roșia Montană gold mine project in Romania.

In March, acknowledging the importance of sustainability for long-term economic stability, the EU introduced the Lisbon Strategy – a 10-year action and development plan for the EU economy.

This was followed in November with the publication of the EU’s ‘Green Paper – Towards a European Strategy for the Security of Energy Supply’, which explored pathways to a sustainable energy future.

In April, Bankwatch held its annual meeting in Šlovice, Czech Republic. Later in December, the World Bank’s Extractive Industry Review published its final report, with a panel of experts recommending that the World Bank cease investments in fossil fuels.

In 2004, alongside the significant expansion of the EU to 25 members with the addition of 10 new countries, primarily from central and eastern Europe, the Union took further steps to promote renewable energy and reduce its dependence on fossil fuels.

In April, during the EBRD Annual Meeting in London, Bankwatch raised concerns about the environmental implications of the second phase of the large-scale oil and gas development on Sakhalin Island in Russia.

In the same month, Manana Kochladze, Bankwatch’s Caucasus coordinator, received the Goldman Environmental Prize for her work on the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline. The award recognised her success in exposing environmental and social violations, leading to crucial project concessions and subsequent official acknowledgements of the project’s failings.

In January 2005, the EU launched the first phase of the Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), establishing the world’s largest carbon market. With the aim of reducing greenhouse-gas emissions, the system set a cap on total emissions by permitting the trading of emissions allowances among companies.

On 16 February, the Kyoto Protocol came into force, marking a significant milestone in international climate policy. The EU played a leading role in its implementation, committing to legally binding emission reduction targets.

That year, Bankwatch celebrated its tenth anniversary and joined Green 10, a coalition of the largest environmental organisations in Europe.

After two years of campaigning, Bankwatch scored a major success when EU support was withdrawn from a hazardous waste incinerator project in Stara Zagora, Bulgaria.

Finally, the EIB organised its first-ever public consultation process for a policy review, responding to our sustained advocacy efforts.

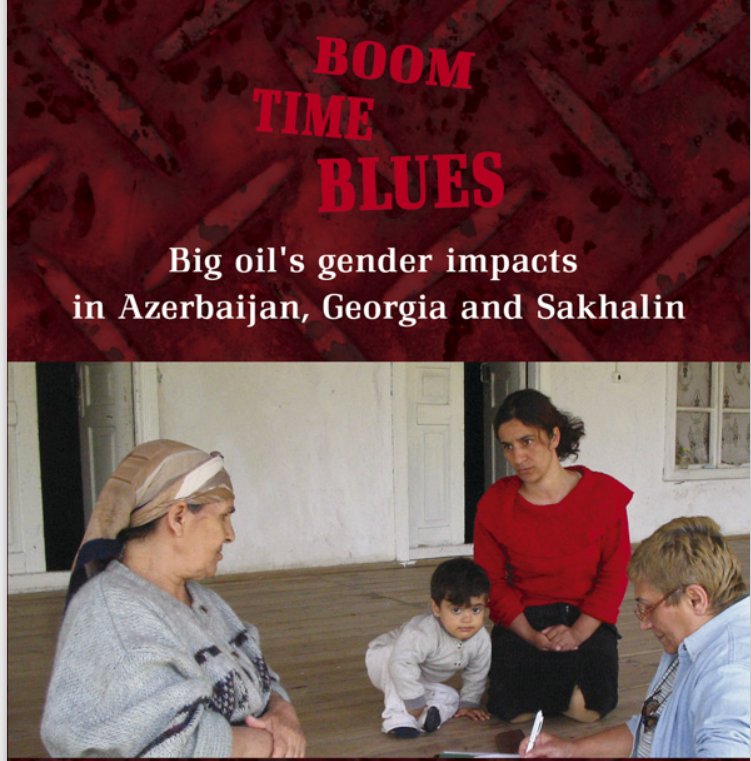

In September, Bankwatch published its widely acclaimed ‘Boom Times Blues’ report, which examined the gender impact of oil projects in Sakhalin (Russia), Georgia, and Azerbaijan. The findings prompted the EBRD to develop its first Gender Action Plan.

In the same month, Bankwatch also released the Citizen’s Guide to European Complaint Mechanisms, enabling the public to make more effective use of EU grievance procedures.

In October, the EU launched its Energy Efficiency Action Plan, setting out policies for reducing energy use across the Union.

In a notable success, Bankwatch played a part in blocking a Canadian-backed proposal to extract copper and gold using cyanide technology in Bulgaria.

In April, Bankwatch published a report on the impact of EU funding plans on climate change, warning that the EUR 177 billion in EU funds earmarked for new Member States risked undermining the EU’s own climate commitments.

Later in the year, we helped to launch Counter Balance, a new Europe-wide coalition aimed at holding the EIB accountable for its environmental and social impacts. Alongside Counter Balance, Bankwatch joined protests at the EIB’s annual forum in Ljubljana, targeting the planned financing of the controversial Šoštanj 6 lignite power plant.

We also organised a fact-finding mission to Vlora, Albania, where construction of an oil and gas power plant had begun with funding from the EIB, the EBRD and the World Bank – despite ongoing concerns, the plant remains non-operational to this day.

In Poland, we marked a major campaign success by helping to protect the Rospuda Valley – a Natura 2000 site – from being damaged by the proposed Via Baltica expressway route.

Finally, in December, the EU signed the Lisbon Treaty, formally introducing sustainable development, including environmental and social dimensions, as a central EU objective.

The EU also agreed on the targets for its proposed Climate and Energy Package, committing to a 20 per cent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, a 20 per cent share of renewable energy, and a 20 per cent improvement in energy efficiency by 2020.

Bankwatch and its Polish member group, Polish Green Network, scored a major success after a seven-year campaign to protect the Rospuda Valley. By strategically applying pressure on the Polish government and the European Commission while leveraging EU financing regulations, we played a pivotal role that led to the Warsaw court revoking the last remaining permit for the original route, resulting in its eventual rerouting the following year.

At the EU level, Bankwatch continued its advocacy to ensure that climate action remained central to cohesion policy and raised concerns around the growing use of public–private partnerships in infrastructure development.

In December, the 14th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP14) was held in Poznań, Poland, bringing international attention to global climate efforts.

In April, the EU formally adopted its Climate and Energy Package, setting binding targets to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions by 2020. In addition, the EU strengthened its European Neighbourhood Policy, placing a stronger emphasis on human rights as a central tenet in relations with its eastern and southern neighbours.

During the year, Bankwatch conducted a fact-finding mission to the Corridor Vc motorway section south of Mostar in Bosnia and Herzegovina. And although the route alignment remains unresolved to this day, the fight continues.

Following a four-year campaign – including petitions and legal action at both Bulgarian and EU levels – Bankwatch and its partners achieved significant changes in Bulgaria’s mining sector. Plans to introduce cyanide leaching at the Chelopech gold and copper mine and at the Krumovgrad gold and silver mine were blocked. As a result, EBRD investments in Dundee Precious Metals were limited to revised, less harmful technologies, leading to an appropriate assessment and the implementation of mitigation measures in Krumovgrad.

The year marked 13 years of Bankwatch campaigning to protect Bulgaria’s Kresna Gorge – an ecologically vital Natura 2000 site – against the threat of motorway construction.

Early in the year, Bankwatch worked intensively to raise concerns about the proposed Nabucco gas pipeline connecting Turkey and Austria, highlighting the environmental and geopolitical risks of EIB and EBRD involvement in the project.

In cooperation with our Macedonian member group Eko-Svest, we launched a campaign to safeguard Mavrovo National Park and the critically endangered Balkan lynx from destructive hydropower developments. Through a combination of formal complaints and public mobilisation, we successfully pressured both the World Bank and the EBRD to withdraw their funding, helping to protect one of Europe’s biodiversity hotspots.

In May, at the EBRD Annual Meeting in Zagreb, Bankwatch drew attention to the climate impacts of fossil-fuel financing, with anti-coal activism emerging as a central issue.

After years of advocacy dating back to 2005, the EBRD began implementing its Gender Action Plan in 2010 – a long-overdue but welcome step towards addressing gender inequality in its operations.

Coinciding with the EBRD’s 20th anniversary, Bankwatch published two reports – ‘Stuck in the Market’ and ‘Are We Nearly There Yet?’ – prompting the bank to revise its transition methodology to include qualities such as green economy, good governance, and inclusion.

In February, the European Parliament adopted a resolution calling for the EIB to develop a strategy for phasing out the financing of projects detrimental to the EU’s climate objectives outside the EU, including certain fossil-fuel projects.

In March, the EU adopted a roadmap for moving to a competitive low-carbon economy, outlining a strategy to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions by 80 to 95 per cent below 1990 levels by 2050.

Throughout the year, we raised concerns about the environmental and social impacts of the significant mining boom in Mongolia, driven by increased foreign investment in large-scale mineral extraction projects.

In April, Russian environmentalist Dmitry Lisitsyn was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize for his grassroots efforts to protect Sakhalin Island’s fragile ecosystems from the impacts of large-scale oil and gas development.

And finally, in May, the European Commission adopted the EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2020, aiming to halt biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation across the EU.

In May, the European Code of Conduct on Partnership was adopted by the European Commission, establishing guidelines for involving civil society and the public in planning and implementing EU cohesion policy.

In August, Bankwatch published a report on the Kumtor gold mine in Kyrgyzstan, contributing to growing parliamentary scrutiny and influencing public debate around the project’s environmental and social impacts.

In September, Bankwatch and Greenpeace raised the alarm over the EBRD’s proposed EUR 300 million loan for lifetime extensions of Ukraine’s ageing nuclear ‘zombie’ reactors.

In October, the first EU Energy Efficiency Directive was adopted, establishing a common framework of measures to promote energy efficiency within the EU to ensure its 2020 target of a 20 per cent improvement in energy efficiency would be met.

In March, the European Commission published a proposal for the seventh Environment Action Programme (2014–2020), outlining priorities such as safeguarding natural capital, protecting human health, and enhancing climate resilience.

In May, the EU’s new cohesion policy regulation was finalised, requiring that all operational programmes include environmental safeguards, with 20 per cent of the EU budget earmarked for climate-related spending.

In July, after sustained pressure from Bankwatch and its partners, the EIB adopted its new energy lending criteria, effectively committing to phase out financing for coal and setting stronger restrictions on carbon-intensive projects.

In November, following years of Bankwatch-led advocacy and legal action citing environmental risks, the EBRD officially withdrew from financing the Ombla hydropower project in Croatia.

Throughout the year, we advocated for the EBRD to help mediate tensions between Ukrainian communities and electricity transmission companies, addressing long-standing conflicts over land rights and infrastructure development.

Throughout 2014, Bankwatch continued to focus on influencing EU funding for sustainability and opposing harmful allocations.

In May, following active campaigning against fossil fuels, Bankwatch scored a significant victory when the EBRD adopted a new energy sector strategy that largely stopped its funding of new coal projects, with the temporary exceptions of Kosovo and Mongolia.

One of our major campaigns during the year highlighted the ongoing threats to the Balkan lynx and Mavrovo National Park. We also advocated against mandatory biodiversity offsetting and engaged in EU climate policy discussions.

Bankwatch’s annual meeting took place in Georgia, where the network was actively involved in environmental issues throughout the year, particularly concerning controversial hydropower projects.

In 2015, against the backdrop of the landmark Paris Agreement and a significant migration crisis stemming from the wars in Syria and Iraq, linked by many to factors including climate change, Bankwatch actively campaigned across south-eastern Europe, successfully stopping or stalling investments in coal in Romania, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia.

At the EU level, we pushed for and achieved the greening of the European Fund for Strategic Investments, highlighting the minimal investment in renewables and energy efficiency by central and eastern European governments using EU funds.

We also held a first fact-finding mission to Ukrainian communities impacted by mini hydropower plants, as documented in our ‘Black Earth’ report, and continued to support movements against large dams.

Our sustained efforts to reverse the impact of polluting coal power and promote cleaner energy in the Balkans yielded important victories in Romania and Serbia.

In January, Bankwatch, in partnership with Friends of the Earth Europe, published its widely circulated report – ‘Climate’s Enfants Terribles’ – highlighting how the mismanagement of EU funds by some of the newer Member States was hindering the EU’s clean energy transition.

In March, the EU adopted the Circular Economy Action Plan, aiming to promote the reuse, repair, and recycling of materials across all sectors as part of its shift toward a more sustainable economic model.

In April, Croatia’s Minister of Economy confirmed that the planned Plomin C coal power plant would not proceed. The project, previously expected to receive financing from institutions including Crédit Agricole, was abandoned amid growing opposition and financing uncertainty.

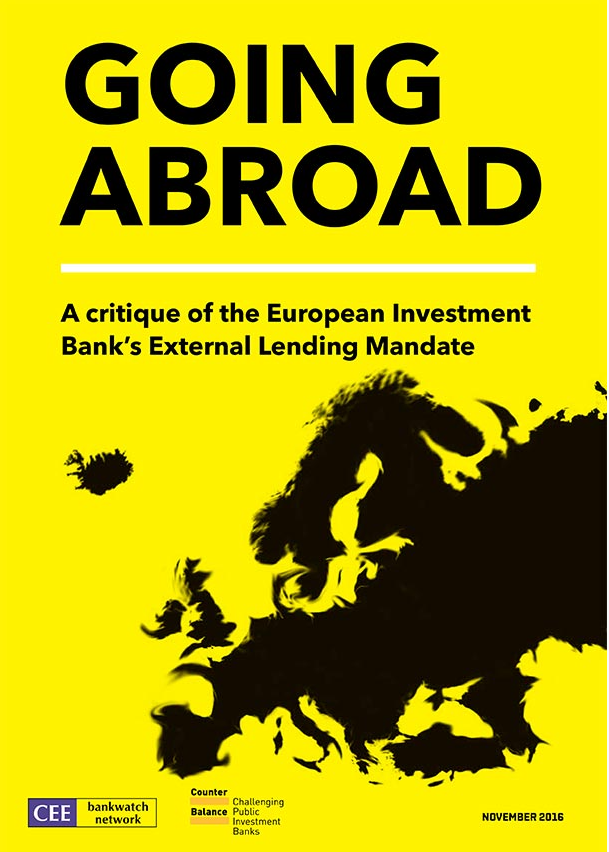

And to round off the year, in November, we published another two major publications: a report co-authored with Counter Balance – ‘Going abroad: A critique of the European Investment Bank’s external lending mandate’ – examining the development impacts and accountability gaps in the EIB’s operations outside the EU; and the ‘Great Coal Jobs Fraud’ report, exposing how coal projects across south-eastern Europe were being justified with inflated or unrealistic employment figures.

In January, the EBRD cancelled its EUR 65 million loan for the Boškov Most hydropower plant in North Macedonia, following our sustained campaigning over its environmental impact.

In Kenya, Bankwatch highlighted the case of an EIB-financed road project where over 100 people were displaced without compensation, in breach of project obligations.

Between April and July 2017, Bankwatch carried out independent air quality monitoring at six sites across the Western Balkans, Romania, and Bulgaria to address gaps in official oversight. Our findings revealed frequent breaches of EU air quality standards for PM10 and PM2.5, underscoring the health risks posed by coal-fired power plants and the inadequacy of official monitoring systems.

In March, we co-hosted a global gathering of nearly 100 river defenders in Tbilisi, bringing together activists from across five continents to strategise for river protection.

And lastly, in November, Bankwatch joined over 30 civil society groups and think-tanks from 28 countries in launching the Europe Beyond Coal initiative, calling for a just and inclusive energy transition.

In June, Bankwatch and Patagonia delivered an unprecedented petition with over 120,000 signatures to the EBRD, urging an end to hydropower financing in the Balkans – the largest energy-related petition ever targeting the bank.

In October, Bankwatch participated in the Human Rights Defenders World Summit in Paris, bringing together over 150 activists to strengthen their advocacy with development banks.

Throughout the year, Bankwatch advanced the concept of a just transition for coal regions, engaging EU policymakers and featuring prominently at the UN climate talks in Katowice in December.

For instance, in Slovakia, Bankwatch supported the development of an action plan for the Upper Nitra region, a pilot area in the EU’s Initiative for Coal Regions in Transition, aiming for a coal phase-out by 2023.

In April, Ana Colovic Lesoska – founder and executive director of Eko-Svest, the North Macedonian environmental research and advocacy organisation – received the Goldman Environmental Prize for stopping EBRD and World Bank financing of hydropower projects in North Macedonia’s Mavrovo National Park.

Throughout 2019, Bankwatch supported efforts to open the Initiative for Coal Regions in Transition to broader stakeholder involvement and contributed to shaping the EU’s EUR 1 trillion Multiannual Financial Framework.

We also helped secure the cancellation of EBRD loans for the Balkan expansion of Ukrainian poultry giant Myronivsky Hliboproduct (MHP) following community complaints, and successfully pushed the EBRD to strengthen protections against reprisals in its updated safeguards policy.

In September, Montenegro officially cancelled the Pljevlja II coal-fired power plant project, previously considered for funding by Czech and Slovak export credit agencies.

In November, signalling a major shift in EU energy policy, the EIB announced it would end financing for fossil-fuel energy projects by the end of 2021.

But perhaps the most significant decision of 2019 came late in the year with the European Commission’s launch of the landmark European Green Deal, aiming to make Europe the first climate-neutral continent by 2050.

In the same month, Bankwatch published the first edition of our ‘Comply or Close’ publication series, exposing chronic breaches of air pollution limits by coal plants in the Western Balkans.

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic radically reshaped daily life across Europe, prompting Bankwatch to adapt its advocacy to new challenges.

As chair of the Green 10 network, Bankwatch urged the European Commission to ensure that national recovery and resilience plans aligned with the European Green Deal. It also pioneered the first civil society assessment of these plans, highlighting poor public engagement and risks to climate objectives.

In July, the EBRD launched its Independent Project Accountability Mechanism (IPAM), replacing its previous Project Complaint Mechanism. The new mechanism was updated to include a new structure and direct reporting lines to the Board, enhancing its functional independence.

In October, owing to the ongoing pandemic, Bankwatch convened the first-ever virtual dialogue between civil society and the EBRD’s Board of Directors, fostering greater transparency and accountability.

In the same month, our inaugural Lung Run was held in Bitola, North Macedonia. Due to the pandemic, the event shifted online, with participants using the Strava platform to track their runs and monitor air-pollution levels around the city’s coal-fired power plant.

In December, the European Ombudsman opened an inquiry into the EIB’s financing of the Southern Gas Corridor, following a Bankwatch complaint alleging that the EIB underestimated the project’s climate impact.

Throughout the year, Bankwatch’s campaign on the Nenskra hydropower project in Georgia led to compliance reviews by the EIB and the EBRD, which found both banks non-compliant with their indigenous peoples policies. As a result, both institutions improved their safeguards, requiring free, prior, and informed consent from affected communities.

In March, over 200 employees of Indorama Agro in Uzbekistan’s Syrdarya region established People’s Unity, the country’s first independent trade union. Bankwatch supported this landmark initiative, advocating for workers’ rights and freedom of association.

In July, the European Commission unveiled the Fit for 55 package, aiming to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions by 55 per cent by 2030. Bankwatch engaged with the legislative initiative, promoting stronger climate action and just transition measures.

In September, Bankwatch and the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air released the third edition of the ‘Comply or Close’ report. It estimated that air pollution from coal-fired power plants in the Western Balkans caused approximately 19,000 premature deaths between 2018 and 2020, resulting in health-related costs of EUR 6 to 12 billion annually.

In November, the Energy Community Ministerial Council confirmed that the public loan guarantee for Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Tuzla 7 coal power plant constituted illegal state aid under the Energy Community Treaty. Bankwatch had long advocated against the project due to environmental and legal concerns.

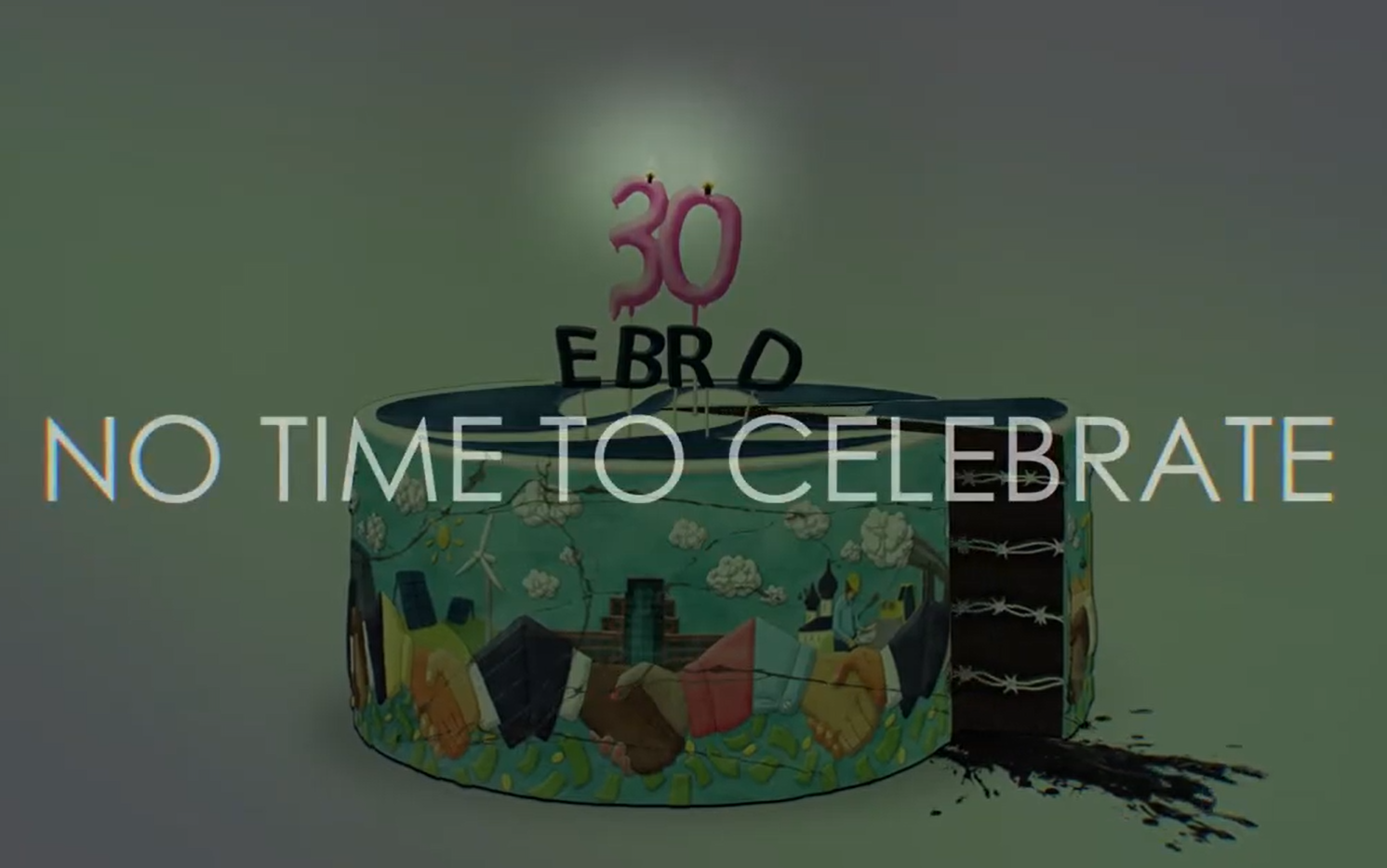

Throughout the year, Bankwatch’s ‘No Time to Celebrate’ campaign marked the EBRD’s 30th anniversary by highlighting the institution’s human rights shortcomings. The campaign contributed to progress on the EBRD’s policies regarding reprisals and human rights due diligence, setting the stage for the 2024 safeguards revision.

Our advocacy and research also influenced several countries to revise their biodiversity plans, ensuring better alignment with EU environmental standards and the EU’s Biodiversity Strategy.

Bankwatch also supported displaced families affected by an EBRD-backed landfill project in the Belgrade settlement of Vinča. The EBRD’s IPAM registered a complaint from the families, leading to negotiations aimed at securing their rights and livelihoods.

In January, the EIB suspended the disbursement of a EUR 200 million loan intended to dramatically increase passenger turnover at Budapest’s Ferenc Liszt international airport. The decision was influenced by concerns we had raised over environmental impacts and alignment with EU climate objectives.

In February, Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, marking a major turning point for Europe. The conflict brought devastation to Ukraine and reshaped energy policies, defence strategies, and international alliances across the continent. In response, Bankwatch rapidly organised alongside its Ukrainian member groups to address the emerging challenges.

In response to the war, the European Commission unveiled the REPowerEU plan in May with the aim of reducing dependence on Russian fossil fuels by boosting renewable energy and energy efficiency efforts. Bankwatch heavily engaged with this initiative, advocating for sustainable and equitable energy transitions.

In November, the third edition of our Lung Run took place in Ugljevik, Bosnia and Herzegovina, gathering 50 participants from eight countries. After two years of virtual races due to COVID-19 restrictions, the return of our live event placed the just transition high on the local agenda in order to raise awareness about the effects of pollution across the region.

In Latvia, plans for a liquefied natural gas terminal were cancelled – a decision reflecting shifting energy strategies in the region and influenced by the broader European push to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and enhance energy security.

Throughout the year, Bankwatch campaigners closely followed the implementation of REPowerEU, the EU’s plan to help Member States address the energy crisis through diversification of supply, increased renewables, and improved energy efficiency.

We also continued to support our member and partner groups in Tbilisi, Yerevan, Belgrade, Sarajevo, Samarkand and Bishkek, while advocating for better targeted investments to strengthen the resilience of Ukrainian cities and communities in their reconstruction efforts.

In May, the EU extended its Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy (2020–2024) until 2027 to align with the Multiannual Financial Framework. The extension was established to reinforce the EU’s commitment to promoting human rights and democracy globally, addressing challenges such as digital rights, freedom of expression, and migration.

In July, the EBRD’s misguided investment in the Vinča landfill project in Belgrade resulted in a problem-solving agreement being signed between 17 Roma households, the City of Belgrade, and the project promoter Beo Čista Energija. The agreement secured adequate housing for the families evicted due to the project, concluding a multi-year mediation process.

Politically, the year was defined by the dramatic escalation in the conflict between Israel and Hamas in October. Across Europe, protests and public debate intensified over the humanitarian crisis and foreign policy responses.

The year closed with the launch of our ‘Beyond Coal’ documentary in November. Created by 2Celsius and Bankwatch Romania, the film depicts the coal phase-out in the Romanian county of Gorj, particularly the challenges communities face as they transition to a greener economy.

In February, an EBRD compliance review vindicated local residents affected by the Corridor Vc motorway project in South Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The review acknowledged deficiencies in public consultation and environmental assessment, prompting calls for rerouting and improved stakeholder engagement.

In April, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina officially cancelled the contract for the Tuzla 7 coal power plant. Subsequently, the promoter Elektroprivreda BiH published a business plan excluding the unit, marking the end of this long-contested project.

In May, the Supreme Administrative Court of Bulgaria definitively rejected a controversial waste incinerator project in Sofia due to unassessed health risks and lack of public consultation. The decision concluded an eight-year legal battle, underscoring the importance of public participation in environmental decision-making.

In September, the EBRD finally cancelled its USD 214 million loan for the Nenskra hydropower project in Georgia. The decision followed findings by the IPAM that the project violated environmental and social policies.

We continued to hold international financial institutions accountable to the communities they serve, pushing for improved safeguards. These efforts notably culminated in the approval of the EBRD’s revised Environmental and Social Policy in December.

Throughout the year, we also advocated for energy transition plans aimed at ending reliance on fossil fuels while supporting social and economic development.

So far this year, Bankwatch has been actively challenging decisions that overlook environmental safeguards, as seen in our request for a review of the European Commission’s approval of the Western Balkans Reform Agendas’ support of fossil-gas projects.

We have also been advocating for stronger environmental policies and funding, such as pushing for enhanced EU biodiversity funding and providing recommendations for national social climate plans to ensure a more just transition.

As the year progresses, we will continue our crucial work in monitoring the impacts of development projects and advocating for accountability. This includes raising concerns about the environmental risks of forest biomass in the Western Balkans and large-scale agribusiness in Ukraine, as well as promoting effective grievance mechanisms at international financial institutions, particularly at the EBRD and EIB.

Watch this space!