Europe’s coming out of the economic crisis is murky, far-right parties across the continent are about to make significant gains in the upcoming elections for the European Parliament, and Russia is wreaking havoc at the EU’s eastern borders. Nostalgia for a European Union of the past is not uncommon: we miss the visionary politicians that founded the Union, we decry the destruction of what used to be “social Europe”.

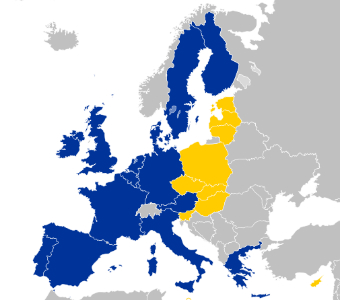

In central and eastern Europe, we face similar problems as the entire block: most countries in the region have been hard hit by the European economic crisis; mainstream political parties have lost the trust of the electorate and fringe candidates – often with populist and even far-right stances – are gaining ground; pessimism about the direction in which our countries are headed is high, as is skepticism towards the EU.

Unlike ten years ago, we cannot hope any more that EU membership alone will do away with all our problems.

Our region has benefited enormously from joining the EU. Freedom of movement, access to labour markets in Western Europe, and easier access to educational opportunities in other countries are just some examples. We have received important sums of cash from the European budget too: Poland alone, the biggest beneficiary, has had a net benefit of 60 billion euros from EU funds since it started the accession process. Our infrastructure has improved, environmental protection standards raised, corruption issues have been brought to light, and our societies are more liberal. There are many distinctions among our countries, but we might be able to agree on these effects.

It’s probably also true that most of us would have expected more out of being members of the European Union. We would have wanted to see even less poverty in our countries, much less corruption, much better functioning economies, a better performing political class and media, less misery overall, and much clearer visions of sustainable future for our societies.

So why didn’t we get as much as we dreamed out of the EU? Not an easy question, but two things can be pointed at: we in the CEE have not tried hard enough; and the EU receiving us was never the unambiguously benign force we had imagined it to be.

At Bankwatch, colleagues from CEE countries are monitoring how the EU budget funds made available to our countries are being spent, particularly when it comes to climate and environment impacts. Right as we are marking this 10 year anniversary, our governments are negotiating with Brussels their national strategies for how to use money from the EU over the next seven years. A big chunk of the over 320 billion euro Cohesion Policy funds from the EU budget will come to CEE. In these negotiations, we can observe at play the two factors described above.

Our governments do what they can to get big allowances out of the EU, so as to have money to implement the infrastructure projects that would keep countries “modernising” and them in power. But when it comes to implementing the EU objectives that come linked to the money, such as making our economies more sustainable and less resource intensive, we see often more lip service and less internalisation of European values. We’re a bit like bad students who don’t really engage with the topics – read, don’t do a lot of reflection on what Europe really is and where it is going – but learn a few paragraphs by heart to pass the exam.

We see it with the national spending plans: the strategies were done without proper participation of interested citizens, even though that was a Brussels requirement, and without proper mainstreaming of the climate and environmental objectives of the EU. All national plans start with lip service to the values of participation, environmental protection, and commitment to the EU values, but the fine print shows it’s a lot of business as usual: big strategic decisions made far away from the citizens and benefiting more the bigger economic players than the long-term well being of our societies. Our governments are failing to develop long-term strategies for decarbonisation, in line with the general EU direction, and instead hope to be able to keep improvising.

Those national spending plans, despite their failings, will eventually be approved by Brussels – after interventions by the European Commission. And herein lies the responsibility of the EU welcoming us too. The EU is a complex animal juggling diverse interests, and some of these go against the stated European values. Lobby by big fossil fuel companies can be very effective in Brussels and capitals of member states. So to some in the EU it will be acceptable that CEE governments don’t quite care about the citizens or about the climate. Or at least they won’t be bothered by it.

We’ll be all quite ok with the compromise. Our governments will present to us the acceptance by Brussels of the national spending plans as a victory, and the money will roll in though we won’t be able to spend it all because we haven’t properly implemented the EU norms and because those in charge of implementation still won’t have all the needed expertise and honesty. And, ten years later, when we again celebrate our EU accession, we’ll probably say the same bitter “we could have done much better”.

Yet it could go another way too: it could be that this 10 year anniversary makes some of us in CEE reflect more and decide to use the opportunities provided by the EU more intelligently. That, faced with the aftermath of the economic crisis, the pressures of climate change and the challenges of social problems we need to resolve, more of us in both eastern and western Europe will get serious about the need to find truly sustainable paths for the entire continent.

Never miss an update

We expose the risks of international public finance and bring critical updates from the ground – straight to your inbox.

Institution: EU Funds

Tags: EU | accession | anniversary | corruption | development | elections | enlargment | environmental standards | progress