Tbilisi’s transport policy conundrums: between resolution and resistance

by Mariam Patsatsia, Bankwatch and Green Alternative

Marina’s daily commute is a series of hurdles. At the bus station, she waits – patiently – 20, 25, 30 minutes for the arrival of her transit. When the bus finally emerges, she boards a crowded interior where space is already an enviable commodity. With each passing bus stop, the air hangs thicker and heavier as passengers pile in, yet hardly anyone gets off before the bus starts to approach her distant suburb. Marina asked the mayor of Tbilisi to one day join her commute in order to witness her daily transportation struggles, but her request fell on deaf ears. She then decided to draw attention to Tbilisi’s public transport woes by fashioning an inflatable doll adorned with the mayor’s face – a peculiar symbol of her disaffection – and bringing the effigy on the bus with her.

In a neighbouring district just beyond the reach of a busy highway, Mar, another Tbilisi resident, embarks on daring journeys on her bicycle. In the car-choked city, she traverses mixed traffic roads into a relative refuge of shared bus lanes, before eventually finding respite on isolated bikeways. She pushes aside enormous trash cans, carelessly discarded on lanes and sidewalks, confronts drivers to ask them to move their illegally parked cars, and calls on police to force particularly entitled and obstinate motorists out of her rightful passage.

The fortitude of these women is admirable. But the efforts of Tbilisi City Hall, responsible for transport reform, are anything but commendable. Criticism is also apt for the international financial institutions that have invested significantly in Tbilisi’s transport planning overhaul, and that are therefore responsible for monitoring its progress and impact.

In 2018, after mounting public pressure and increased evidence of Tbilisi’s troubling car-focused planning, city authorities set out to decrease the city’s car dependency by prioritising public transit and developing better infrastructure for walking and cycling. International financial institutions, primarily the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and Asian Development Bank (ADB), have provided critical investment for public transport. Other donors, such as Germany’s KfW, allocated funding for an intelligent traffic management system and for green corridors that integrate user-friendly cycle paths and footpaths.

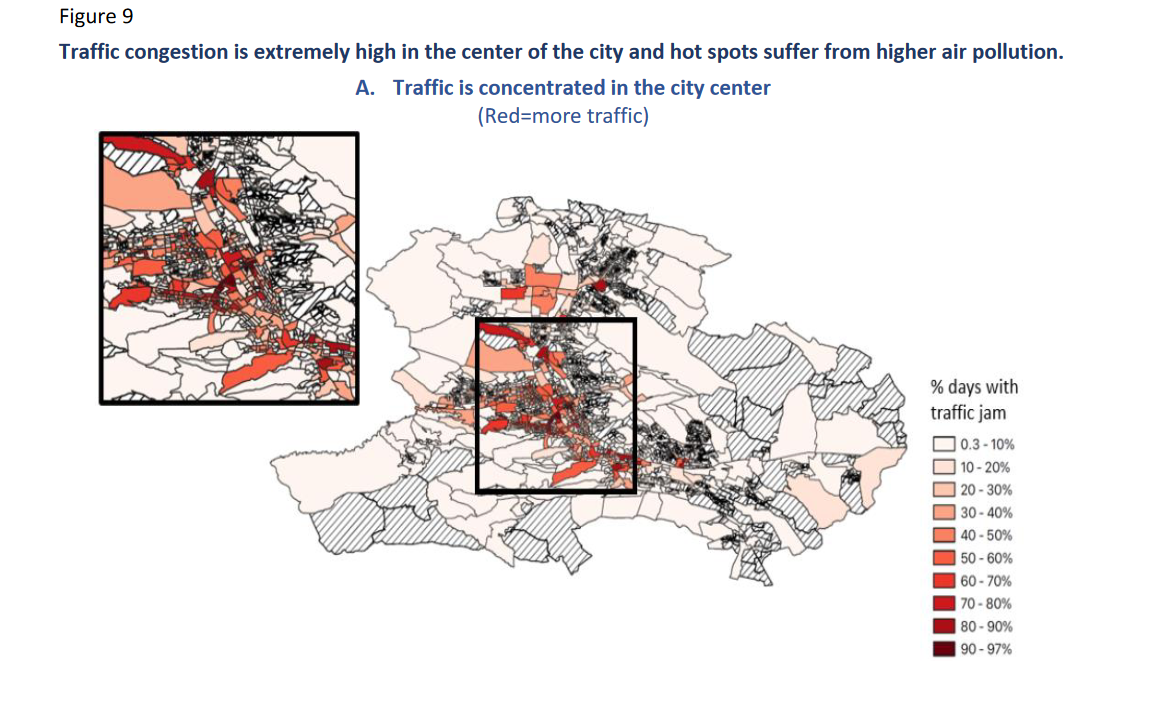

The city’s revamped transport policy was aimed at alleviating congestion and improving air quality. And its declared path could have brought the desired improvements. Yet, five years after announcing the change in the city’s transport planning approach, car ownership is still rapidly increasing, while public transport services remain unreliable and poorly equipped to accommodate growing transit commutes. Over the years, congestion has also worsened and continues to impact air quality – the average monthly PM2.5 concentration in Tbilisi is four times higher than the WHO’s annual threshold. Nitrogen oxides are another main pollutant on the rise and are directly connected to the exhaust from the ever-growing number of cars. Air pollution in Tbilisi has important social ramifications as well: poorer and less-educated households are more exposed and have a lower capacity to adapt to its consequences.

As the necessary reforms were being drawn out, transportation problems weighed down the city. Criticism of City Hall’s inertia and of the slow-moving changes grew, and in autumn 2022 the reforms gained renewed speed. This led to simultaneous work on several important initiatives, from launching the rehabilitation of a main avenue to purchasing bi-articulated buses – some three years later than promised – to remedy overcrowding. These initiatives, however, could also be jeopardised by further delays – a constant feature of Tbilisi’s transport projects.

The majority of city residents, according to a recent public opinion poll from Green Alternative, think that City Hall has been working on reforms ineffectively and without adequately considering their needs.

Transport policy at a standstill:

on neglecting sustainability

In 2019, the Tbilisi Land Use Masterplan, the city’s key long-term strategic document, officially declared compact, transit-oriented development a guiding principle for the city’s future urban growth. But in practice, Tbilisi’s transport policy has been disconnected from the very urban development it was meant to shape and be shaped by. Instead of preventing and restricting urban sprawl, the city has allowed the rampant development of suburban areas in Tbilisi. It has also repeatedly issued permits for towering, multi-storey dwellings and is currently mulling over greenlighting the construction of skyscrapers with little to no consideration for their impact on the city’s transport system.

In this context, Tbilisi’s transport policy has been limited and constrained. The city’s Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan (SUMP), which is crucial for better integrating sustainability and establishing a guiding vision and priorities for transport in the city, has remained in a perpetual state of development since 2019. The advancement and further adoption of the SUMP by the city assembly would provide vital institutional support for the transport policy and ongoing reforms. Furthermore, it would enhance transparency by outlining essential projects slated for implementation and would empower citizens to hold the city accountable for its commitments. In August 2022, as a contract with Ramboll (the consultant responsible for preparing the plan) was expiring, the company had submitted only four out of 16 deliverables requested by the transport authorities. City Hall opted to prolong their contract for one more year, until September 2023.

The rhetoric emanating from City Hall to endorse the transport policy has grown redundant, characterised by an overwhelming focus on technical jargon, often involving traffic and passenger flows, problematic nodes, bottlenecks, and the unconventionality of Tbilisi’s roads. Regrettably, the discourse has largely neglected essential social, gender-related, and environmental considerations: matters of equity, safety, social inclusion, urban landscape quality, soil conservation, climate change and reduction of energy consumption have been conspicuously overlooked in the political leadership’s speeches, as well as in those of the transport authorities. Perhaps the only exception in this regard is air quality, but it could be argued that the attention given to this topic is still grossly insufficient compared to the precarious levels of air pollution in the city. Tbilisi City Hall has notably also refrained from explicitly labeling its transport policy as sustainable. Out of six speeches delivered by the mayor exclusively on transport reform between 2018 and 2022, only one – made in July 2020 – had such a reference.

City Hall’s commitment issues:

on backtracking and lack of enforcement

The political leadership of City Hall has been hesitant to fully embrace genuine and comprehensive transport reform with sustainability at its core. The lack of a unanimous commitment to the reform among City Hall and its ruling party can block the choices of transport professionals in the city administration – this has been a repeated warning and concern. And the perceived unfavourable political implications associated with sustainable transport reforms within the city’s leadership has taken its toll on the progress of such reforms.

Bus lanes in Tbilisi are also being debated due to the associated injustice of their use. The term ‘Škoda-lanes’ has emerged as an informal name for them, as government vehicles, often of the brand Škoda, exploit the lanes to bypass congestion. Bus priority measures should foster social and economic equity by facilitating better travel for public transport users in Tbilisi – largely comprising women, students and low-income individuals. Instead, City Hall has failed to prevent the exploitation of bus lanes by the very people – the police and other authorities – who should enforce priority rules.

Cars, five in total, parked in a bus lane outside of a police station in the Saburtalo district on 29 June 2023. Yellow road markings indicate bus priority. Photo credit: Mariam Patsatsia| Green Alternative

Bike lanes have suffered the same fate. Even though the city has constructed some 22 kilometres of dedicated bicycle paths over the past seven years, illegal parking in these lanes and their use for evading congestion remain prevalent. Furthermore, even though the city developed a cycling masterplan for Tbilisi over a year ago, it has not yet been shared with the broader public; meanwhile, City Hall has already begun to defy its recommendations. Despite the masterplan’s guidance for the installation of isolated bike lanes on University Street, which is home to several university campuses and thousands of students, the ongoing redesign of the street fails to incorporate separate lanes for cyclists. And cyclists are not happy with the law enforcement either. The police are ‘the biggest problem, because when it comes to enforcement, they do next to nothing’, said Mar, a cycling advocate in Tbilisi.

Public participation woes: on commanding attitude

Public participation and democratic involvement play a vital role in ensuring the sustainability and quality of decisions on mobility and transport planning with the aim of overcoming reliance on cars. However, in Tbilisi, city authorities have been reluctant to engage the public in decision-making regarding the ongoing reform processes. They have overlooked the public’s concerns and have completely neglected to do any outreach or campaigning on their policies.

‘I tried to reach out to City Hall and city assembly deputies, but it did not yield any results’, said Marina, the activist who has tried to shed light on the public transport issues in the Vashlijvari district. Alongside her neighbours, Marina has campaigned and diligently filed letters to City Hall for years, yet these endeavours resulted in a single meeting with the Transport and Urban Development Agency (TUDA) last summer. The encounter proved to be far from pleasant, as, according to her, officials constantly tried to quiet Marina and another participant who expressed criticism. Nevertheless, Marina made herself heard loud and clear. The reforms implemented in the system, she contended, failed to resonate with and address the needs of residents, exacerbating waiting times and forcing people into the cramped confines of overcrowded buses coming from and going to neighbouring districts.

‘It is necessary to consider the opinion of the population, and it would certainly be desirable to share their plans, their visions. [Now] they are just ignoring us,’

Marina said, offering a way forward to transport authorities.

Bike activist Mar and her community of cyclists have managed to forge more collaborative relations with TUDA by setting up a joint working group. This has created a space for cyclists to share their views on improving cycling infrastructure and promoting active mobility. Mar says transport authorities have been considerate of their less divisive proposals concerning bike racks and the tweaking of existing lanes to ensure better safety, but they have been reluctant to follow the group’s lead on more complex issues such as ensuring the installation of bike lanes on University Street. City Hall has indicated it is not willing to reconsider.

‘The problem for us is that there is a masterplan, but they are not following it. This is a step backwards… and it’s a hindrance to the reforms process as a whole’, Mar said, underlining that opposition to the reforms from some people, including those in power, is expected, but it is not an excuse for City Hall to give up on its plans. ‘They have to protect their own transport policy’, Mar added.

TUDA’s response to our inquiries about their communications strategy and public consultations lacks specificity. TUDA claims to address local concerns through daily meetings and by monitoring ongoing issues, while utilising social media for communicating on policy and reform efforts. However, their reliance on these tactics alone fails to demonstrate a comprehensive approach to public participation and lacks essential elements such as a dedicated transport policy website and targeted information campaigns. Transport authorities also rely heavily on streamlining information from news media that set the direction of the conversation, often concentrating on challenges faced by drivers, and paying little attention to other mobility actors such as pedestrians, cyclists and transit users.

Monitoring impact:

on the responsibilities of international donors

The extent of international financial institutions’ involvement in Tbilisi’s urban mobility, especially that of the EBRD and ADB, who have been part of the process since the beginning, points to the responsibility of these institutions to ensure the success of public transport reform in Tbilisi as well.

Both the EBRD and ADB have been made aware of the shortcomings of public participation within Tbilisi’s public transit projects. ‘There is no public stakeholder process in these schemes, and public views are not considered until after implementation’, international consultants for TUDA wrote about the department’s approach to designing traffic schemes in 2020. Similarly, the EBRD consultants highlighted that Tbilisi Transport Company, responsible for bus and metro operations, has not undertaken consultations concerning their projects, while information disclosure had been largely limited to ongoing communication about its services. Even though a joint stakeholder engagement plan (SEP) for EBRD-funded metro and bus projects was released, there is no evidence suggesting the activities outlined in the SEP have been carried out. And it is not clear what steps the banks have taken to ensure improvements in this realm within their respective projects.

Regarding information disclosure, although non-technical summaries and stakeholder engagement plans have become available after we requested the documents for the EBRD-funded projects, more concrete outputs, such as research from technical cooperations, still remain unavailable. The involvement of the ADB and its multi-donor trust fund Cities Development Initiative for Asia (CDIA) in urban transport projects has allowed for some transparency, with evaluation reports and technical notes from their projects with TUDA becoming available on the ADB or CDIA’s websites. Notably, however, some of these reports (one prepared in 2017, another in 2020) were shelved for several years before they were finally published in March 2023.

Everything, everywhere, all at once(?):

on the new pace, accompanying challenges,

and some wins for the reform

Amid repeated criticism, Tbilisi’s transport reforms gained some momentum in the autumn of 2022. Bus lanes and zonal parking have expanded, key streets have been redesigned, metro stations are set to close for renovation, a major avenue is undergoing construction, long-awaited 18-metre buses – crucial for addressing overcrowding in mass transit – are finally being purchased, and a depot to house them is being built. The convergence of the ongoing projects shows just how late City Hall was in taking up these initiatives. And as experience has shown time and again, none of these projects are immune to further delays. City Hall should ensure that these initiatives are completed as soon as possible, but also with diligence and with care for the people. Along with the accelerating pace, it is critical for City Hall to improve its public outreach, communication and open forums for public engagement.

This will also allow City Hall to better consider the social, gender-related and environmental aspects of the ongoing reform. One of the key changes in the metro system relates to improving accessibility; this cannot be achieved unless individuals with disabilities become part of the process. Furthermore, issues such as widespread sexual harassment and gender-based discrimination in public transport, which have been widely overlooked, will not be solved unless women and sexual and gender minorities are allowed to engage in designing interventions.

The shift of attention towards public transit, improved pedestrian infrastructure and better opportunities for active mobility is a win for the policy, but City Hall must defend its progress instead of undermining it.

Drivers vs. transit riders: on public opinion survey results

Evidence for many of the issues laid out above are supported by the results of a public opinion survey organised by Green Alternative on Tbilisi’s transport policy and the related public outreach and engagement. One critical finding from the survey is that drivers and transit riders view transport policy and reforms in starkly different terms. Transit users are more likely to support the policy, are much more likely to consider advancing public transport to be more important than developing car-centred infrastructure, and are overwhelmingly supportive of bus priority measures. At the same time, both drivers and public transport users are very likely to think that transport policy and reforms do not take their needs into account. Notably, the majority of the people surveyed think City Hall does not ensure public participation in decision-making on transport reforms. This could well explain why transit riders feel discounted in the very process that is supposed to improve their mobility.

In conclusion: on a path forward

In 2018, the city of Tbilisi arrived at the only viable and sound resolution to its transport problems by making the development of public transit a priority. But the reforms, although enjoying popular support, have been opposed by many drivers, and more prominently have been negatively influenced by the ruling political elite. The result is a waning faith in the process of change and a belief that transportation decisions are betraying those they should be helping the most – transit riders and cyclists. Shortcomings on bus priority enforcement, the decision to allow some taxis in the transit lanes, and backtracking on installing bike lanes on University Street all undermine the process by making commuters and cyclists worse off. Meanwhile, the rising number of cars continues to impact air quality and thus the quality of life in the city. Still, the city’s renewed reforms pace and ongoing projects, critical for improving public transit, provide a glimpse of hope that collective transport modes and active mobility can be enhanced and improved in the city.

City Hall’s shaky commitment to its declared objectives, along with these contradictory developments, make the transport policy and accompanying reforms a Janus-faced beast, unsure of its own course of action. But beyond the halls of power, on the streets of Tbilisi, women like Marina and Mar do not dither. They give a voice to exhausted commuters cramped in overcrowded public transport and to assiduous cyclists riding on unsound, unaccommodating roads. They are showing the city the way forward, and those in power should most certainly hear them out.

Read Bankwatch’s recommendations for City Hall and international financial institutions here.