Aqueduct in Italy breaches EU laws and endangers biodiversity

by Walter Meloni, CEE Bankwatch Network

Farfa River. Photo: Sarah Kashna

In times of pressing climate and biodiversity crisis, the Lazio region and the Italian government are supporting a controversial project to double the Peschiera–Le Capore aqueduct, breaching several EU Directives, and not taking into account people who live in the area and their needs. Moreover, the project, partially supported by EU funds, could potentially endanger six Natura 2000 sites and already exploited local water resources.

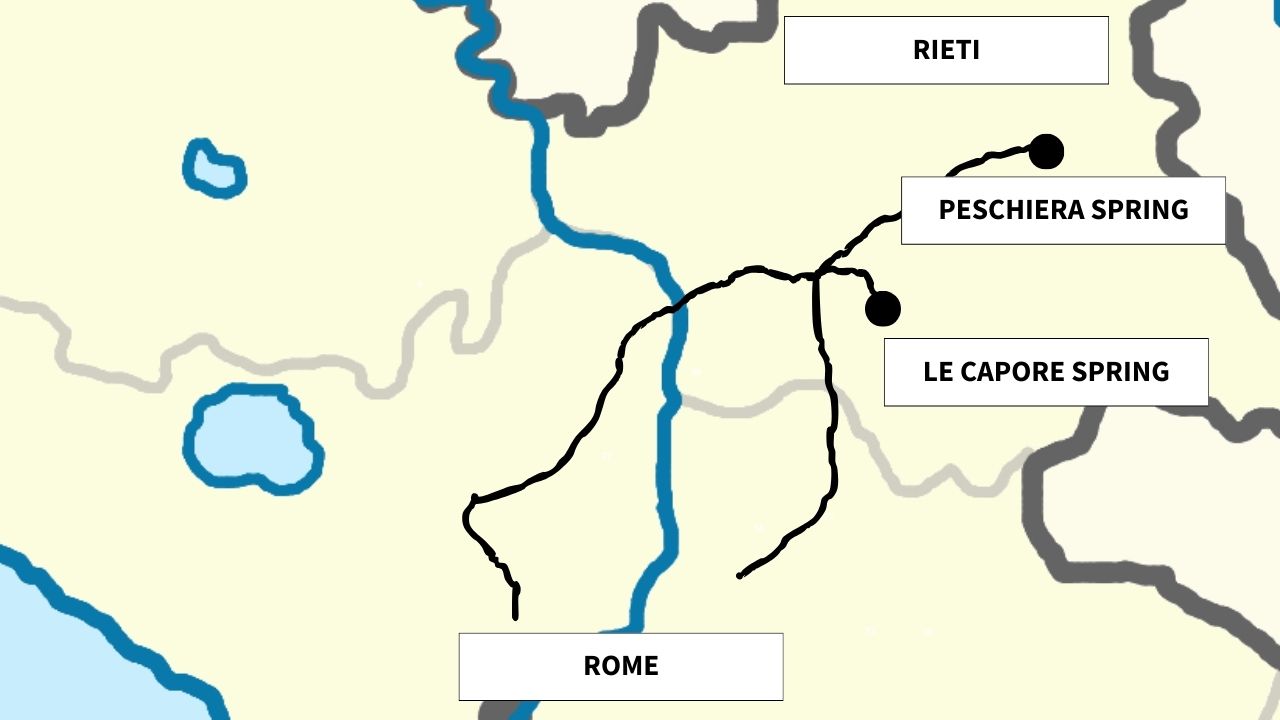

In 2022, the Lazio region in central Italy approved the proposal submitted by the multinational Acea ATO2 S.p.a. and the Municipality of Rome to double the Peschiera–Le Capore aqueduct. The aqueduct is the main source of water for the habitants of the area. It starts from the Peschiera and Le Capore Springs and runs 130 kilometres up to Rome. The plan is to raise the average flow from 13,500 up to 18,000 litres per second. The investment is worth EUR 1.2 billion, and qualifies as the most expensive undertaking in the water resources sector on a national level as part of the Italian recovery plan.

However, civil society organisations have pointed out that the aqueduct is an infringement of the Water Framework Directive and the Directives related to the Natura 2000 Network.

Further exploiting an already overused natural resource

The aqueduct, located in the north-eastern portion of the Lazio region in the Province of Rieti (central Italy), is the main source of water for more than 3 million inhabitants in Rome, and in many municipalities surrounding of Rieti and the lower Sabina region. Out of this volume, 4,500 litres per second are sourced from the Le Capore Spring, with the remaining 9,000 litres per second coming from the Peschiera section.

The Farfa River originates from the Le Capore Spring, a watercourse that, in the past, ranked among the Tiber River’s major tributaries. Nevertheless, its resources are increasingly scarce – in 2017 its flow rate hit historical lows of 200 litres per second due to Acea’s water abstraction and the lack of planning and regulation of the Lazio region. According to the Tiber River Basin Authority, its ecological outflow, the volume of water necessary for an aquatic ecosystem to continue to thrive and provide essential services, is 1,600 litres per second.

Despite its importance, the ecological outflows of the Velino and Farfa rivers were not identified in the mandatory environmental impact assessment (EIA) to double the aqueduct. In addition, there is no mention of the impact of the project on the state of the Farfa and Velino water bodies.

‘The Peschiera Spring is the biggest freshwater spring in Europe, but this does not mean it could not be impacted by climate change and should be drained without considering alternatives. The preservation of this water volume is crucial to prevent another ecological catastrophe that could affect the spring and its rivers,’ said activists from the non-profit Postribù.

This spring gives rise to a river bearing the same name, serving as the primary tributary of the Velino River. With a natural flow rate that has already dropped below 16,000 litres per second, the Velino River could be the next victim of the aqueduct.

Doubling the aqueduct endangers six Natura 2000 sites

This project raises significant concern due to the potential environmental impact on the affected water bodies and the already endangered and highly sensitive ecosystems that depend on them.

‘The doubling of the aqueduct could destroy the Velino River, the Peschiera and the Natura 2000 sites that depend on them, as happened to the Farfa River,’ said Postribu’s activists.

According to Acea, it is essential to double the capacity of the aqueduct to increase the average water flow of 1,000 litres per second. However, this project would require not only the construction of a 27-kilometre water supply network, but also river diversion works to increase its capacity, potentially threatening six Natura 2000 sites. These aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems play a crucial role in both the socio-economic well-being of the local population and in the ecological context of the area, due to their remarkable complexity and rich biodiversity.

The project would particularly impact the Piana di San Vittorino–Sorgenti del Peschiera, which is home to forests of white willow and holm oak, protected bird species such as the red-backed shrike and the common kingfisher, and the lesser mouse-eared bat. These species rely on the springs, lakes and rivers that the aqueduct is threatening, as indicated in an assessment by the Lazio Parks Authority.

Furthermore, an increase in water abstraction would clash with the objective of Natura 2000 and the EU Habitat Directive. These guarantee the conservation of the habitats and species of fauna and flora of community interest and are designed to maintain or restore the biological balances in place.

Failing to comply with the Water Framework Directive

Locals and activists state that the doubling of the aqueduct would openly breach the Water Framework Directive. Especially the objective of preventing the qualitative and quantitative deterioration of water resources. As stated in the Directive, the sustainable use of water resources by individuals and businesses is paramount in order to ensure the health of rivers, lakes and seas but also to restore the fragile ecosystems that rely on them. Moreover, Member States must, through the implementation of the River Basin Management Plans (RBMPs) and Programmes of Measures (PoMs), mitigate the adverse impact on the water body’s status and restore, when necessary, all bodies damaged.

Nonetheless, according to civil society groups these requirements are not met by the project under consideration. The project doesn’t mitigate the adverse impact on the water bodies, and moreover doesn’t apply the ‘do not significant harm’ (DNSH) principle and the goal of avoiding harmful risks to the environment.

‘This is not just an environmental battle,’ said Postribu’s activists.

‘We want to make it clear that the Italian government and Lazio region are not doing enough to mitigate the negative impact on the Farfa, Peschiera and Velino rivers. Eliminating the loss in the Roman water system – which currently stands at 40 per cent and is equivalent to 10,000 litres per second – is a better choice than giving money to destroy our environment.’

Acting against the needs and interests of the local community

Non-governmental organisations such as Postribù and local groups such as Balia Dal Collare have denounced the alarming lack of public participation and stakeholder engagement. The public consultation did not address the concerns of local communities, especially those related to the concessions for water extraction, not only before the project was approved but even during the environmental impact assessment. Moreover, the discussion did not address the option of proposing measures that would ensure systematic changes in drinking water consumption, such as the development of a dual water network in Rome.

Postribù and experts call on the government and the Lazio region to cease the speculation on water resources and to consider the well-being of local communities and the environment, as they are the ones that could suffer the most.

‘We must adjust Rome’s water supply demands and align them with the needs of the environment and local communities. In the middle of the climate crisis, it’s time for a participatory and sustainable model of water management,’ said experts.

The doubling of the aqueduct, which shows similarities with the cases followed in the last two years by the Citizens’ Observatory for Green Deal Financing, is not an isolated but rather a widespread practice in Italy. In fact, Peschiera–Le Capore is one of several high-impact projects included in the recovery plan that have been accelerated under the new EIA procedure adopted by the Italian government. Projects of this scale are not subject to rigorous EIAs, and technical issues tend to be hastily addressed under the guise of urgent investment needs. Additionally, the 30-day period given to stakeholders to provide comments on the EIA is considerably shorter than the standard 60 days, and consultations typically proceed without the proper involvement of local communities.