Heating in the region is still largely based on fossil fuels or wood, the district heating networks are in dire condition, and in poorly insulated buildings winter is not as cosy as it could be. Authorities across the Western Balkans need to pay much more attention to planning and implementing clean and modern heating solutions.

Maja Kambovska, District Heating Coordinator | 20 April 2021

If you live in the city of Skopje, North Macedonia, it is likely that you will find yourself in an apartment in a block of flats built somewhere around the 1970-80s, with district heating that, during the colder half of the year, works between 6am and 10pm. It’s a “take it or leave it” service, with no possibility of regulating the temperature in your rooms, no option of turning on the heating on a cool September day, or turning it down when it is 15 degrees outside in January. This was my experience growing up here in the 1980s, and it still is today, in 2021.

The situation is largely similar throughout the Western Balkans. But it doesn’t have to be this way. In recent years, people have become more vocal about wanting quality heating in their homes, also because of the toll that outdated heating systems have been taking on their health. As soon as winter starts, the media is flooded with reports and warnings about alarming levels of air pollution exacerbated by heating. That is because coal, gas, heavy oil and wood are the main heating fuels in the region.

For example, the share of coal in district heating in Kosovo is 94%, and concerning individual heating, an estimated 62% of households in North Macedonia are using wood. In addition, many households across the region use old-fashion, inefficient electric heaters to warm their houses, which are costly and drive demand for electricity, including from the region’s heavily polluting coal plants.

While governments in the region are contemplating how to decarbonize their energy sectors and address air pollution, it seems they only mean electricity. The heating sector does not get the attention it deserves – either that, or they turn to fossil gas, as has happened in Serbia.

District heating needs to be part of the solution

In the Western Balkans, district heating is used in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia and Serbia, and there are plans to build a district heating system in Montenegro. Indoor heating and hot water supply account for 43% of energy consumption in the Western Balkans. And of all district heating in the region, a staggering 97% is based on fossil fuels and only 3% on renewable energy. And even this renewable energy is mostly biomass, the sustainability of which is currently subject to vigorous debate.

Apart from their dependency on polluting fuels, district heating systems in the Balkans are characterised by outdated and leaky pipelines, and a distribution network serving buildings with poor energy efficiency performance. But instead of seeking easy short-term solutions to patch the systems, authorities should focus on leapfrogging into the most cutting-edge heating systems that integrate various solutions of different scales, adapted to individual locations.

Let’s take the Tuzla example, a city in Bosnia and Herzegovina, notorious for its polluted air due to a lignite power plant that provides heating to around 23,200 households as well as public and commercial buildings. The city has been making efforts to address the situation by providing subsidies for heat pumps and for external insulation of buildings, and by taking measures to reduce the costs for connection to the network in an effort to attract new customers.

However, what Tuzla actually needs is a systemic and long-term solution. And this should not be to construct a new lignite-fueled unit, with the excuse of providing heating to Tuzla residents. Rather, the city authorities should figure out how to provide clean, affordable heat by exploring the local potential for renewables and heat storage, while using the existing infrastructure and focusing on energy efficiency measures in buildings and the distribution network. It requires political will on all levels, and a recognition that, ten years down the line, coal will become way too costly, not just economically, but also in terms of health and environmental costs to be worth investing in in the first place.

A modern, clean heating system that starts operating in 10 years from now, needs to be planned immediately.

In locations where they already exist, like Tuzla, district heating systems are old, inefficient and polluting, and they are not consumer oriented. In communities where district heating is planned, the proposed systems often revolve around designs that were popular 40 years ago, like a single source central system, such as a gas or biomass plant.

The town of Pljevlja in Montenegro has been promised district heating since 1982. Instead, for the past four decades people have been suffocating on air pollution from a dozen lignite-fueled boilers feeding a local network that serves around 390 households in the centre of the town.

The authorities plan to convert the country’s only coal power plant into a co-generation plant which would supply heating to the town of Pljevlja. Replacing a number of small polluting boilers with one single polluting source could perhaps have worked in 1982, when the number of alternatives was limited. But technology has evolved so much since then.

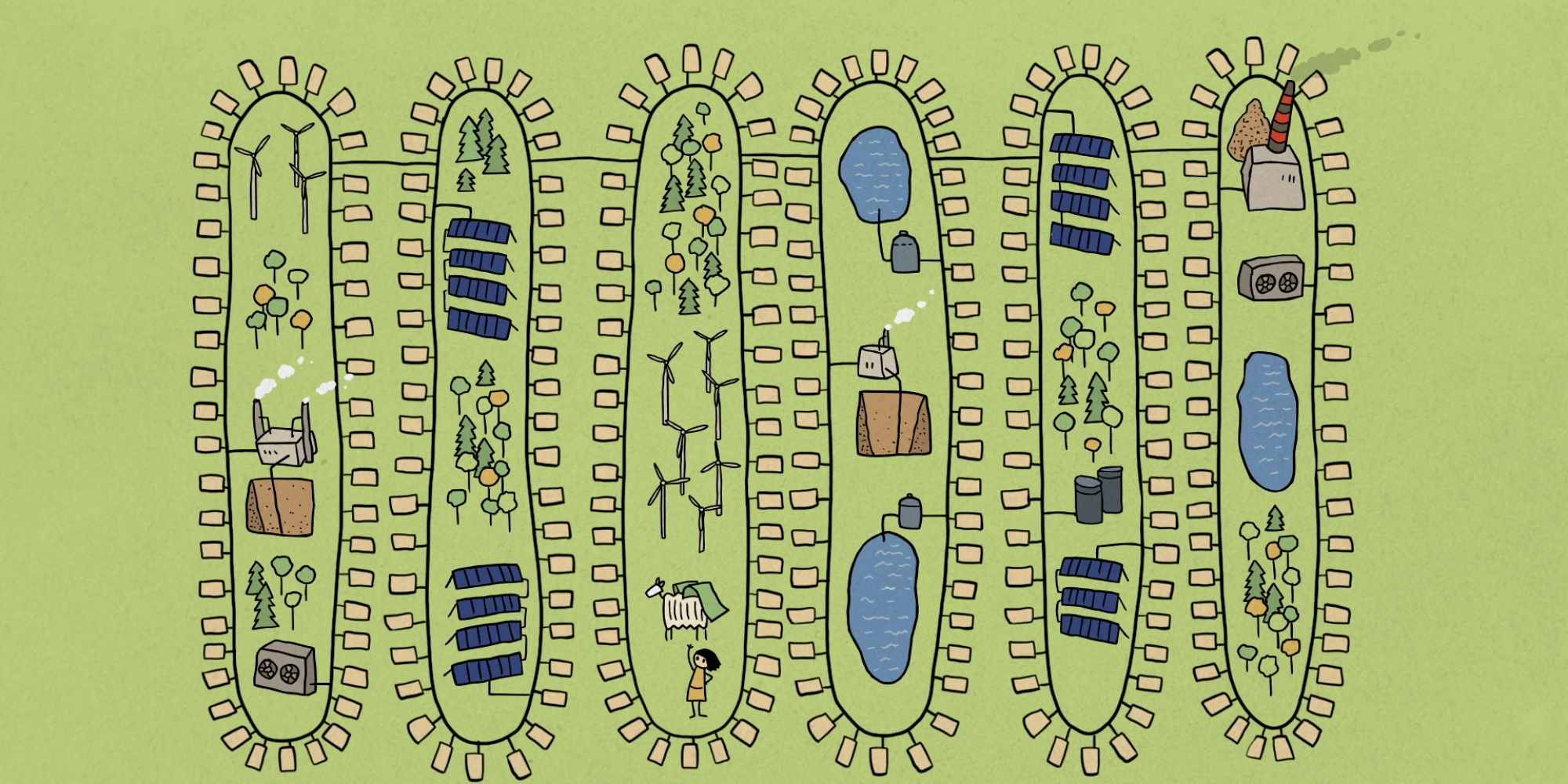

District heating is a complex topic that requires progressive thinking how to modernise all aspects of the system – low-temperature, multi-source solutions on the supply side, such as the use of excess heat from industrial processes or data centers, local renewables potential like solar or geothermal together with heat storage, modern technologies like heat pumps, in combination with energy efficiency measures at the level of the network and on the demand side in order to bring down heat demand.

The localised nature of district heating systems means they should be transformed with a bottom-up approach. The initiative must come from the municipal authorities and local communities, but national and international stakeholders have an important role in integrating clean, modern solutions into national strategic and policy planning. Funding is already available for national and local governments willing to develop such projects, and there are „best practice“ examples from around Europe.

On the path to decarbonisation, which Western Balkan leaders have committed to achieve by 2050, district heating is too big an elephant in the room to be ignored. One of the reasons it has been sidelined for years, even by EU policymakers, is the absence of a „cross border dimension“ that would render it an issue of regional and Europe-wide interest. District heating by nature is primarily a localised, municipal service. But the effects of inefficient heating systems, in the form of air pollution, health and environmental hazard, economic and social costs, extend well beyond municipal and national boundaries.

No country can achieve the necessary emissions reduction targets without aggressive measures to make heating systems clean and smart. At the national level, the ongoing National Energy and Climate Plans (NECP) processes are the place to plan for heating related measures. Recognizing this as a regional concern, in late 2020 the Energy Community launched a heating and cooling platform, with the aim of mobilising the participating countries and stakeholders to exchange information and ideas around this topic.

As a district heating consumer, I often ask myself when can I expect to come back to a home where I can adjust the temperature, control how much I consume and pay at the end of the month, knowing that it is also safe to breathe outside in wintertime because Skopje is heated from clean sources?

Once a district heating project is planned, it would take several years to mobilise funding, secure building permits, carry out construction works, and actually put in place any new technology. That is why planning progressive, locally adapted solutions that work for citizens, for the economy, for the environment, and for the long term, needs to start immediately across all the Western Balkan countries.

Never miss an update

We expose the risks of international public finance and bring critical updates from the ground – straight to your inbox.

Theme: district heating | Western Balkans | fossil fuels | renewables |

Project: District heating | Fossil gas

Tags: Western Balkans | district heating | fossil fuels | renewables