This article first appeared on openDemocracy.net under a creative commons licence (CC BY-NC 4.0).

“Of course we need a different energy model,” Alberto Santoro states emphatically. “It is not enough to simply replace fossil fuels with renewable energy sources. Who controls the energy is just as important.” Alberto lives on his family’s farm in the heel of southern Italy. Olive trees are scattered over his land. He grows food, keeps a few animals and rents a couple of rooms to tourists who visit the beautiful Puglia coastline.

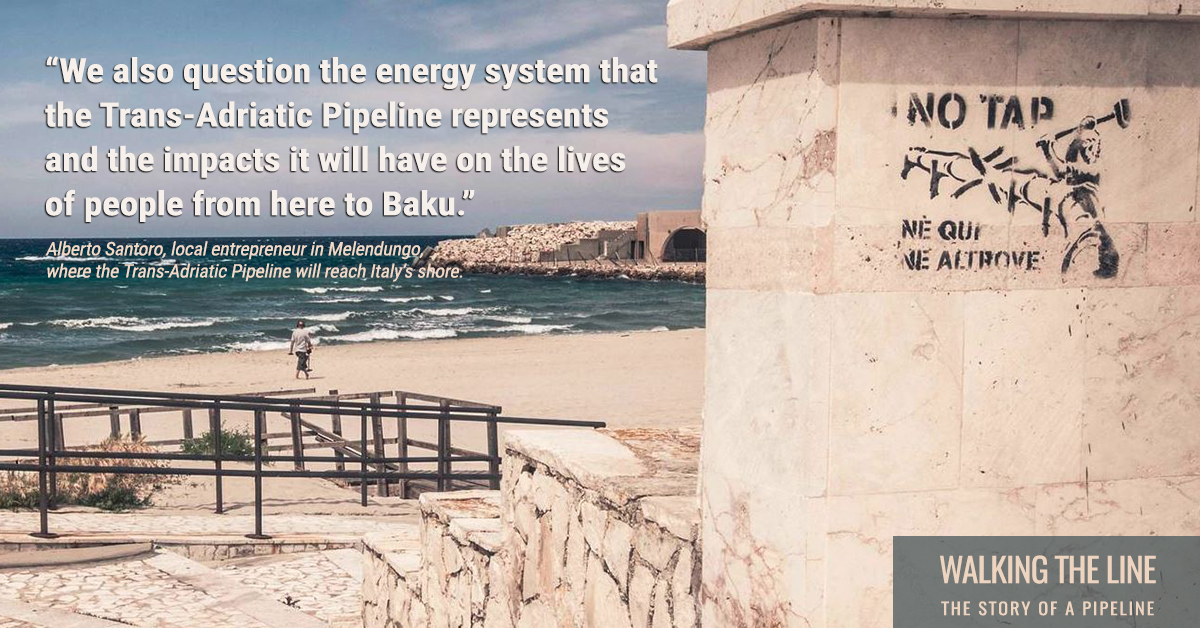

Alberto is a member of just one of three communities we spoke to for an interactive documentary that follows the projected route of a new pipeline from the capital of Azerbaijan to the coastline of Italy. He has more reasons than most to worry about our planet’s energy model.

In recent years, Alberto has found himself at the frontline of a fight against a huge piece of fossil fuel infrastructure – the Euro-Caspian Mega Pipeline. This gas pipeline will extend over 3,500km, from the coastline of the Caspian Sea to the beaches of Puglia through six countries. Despite falling gas demand in Europe, this new pipeline is planned to be built at a cost of $45 billion.

“This concerns our future”

The Euro-Caspian Mega Pipeline will create a giant construction site across Europe. Trucks and excavators will rip up farmland, thousands of villages, forests, deserts and the seabed of the Adriatic. In response, the community in Puglia have organised a tenacious campaign.

We met Alberto on his farm. He told me he was worried about the impact of the pipeline on tourism, fishing and agriculture, especially the cultivation of olive trees, which is a key source of income in the region. Alberto felt he had to act: “This concerns our future. As citizens we have to get involved, nobody will do it for us.”

Photo by Laure Cops, Wouter Vanmol and Berber Verpoest.

With a small group of concerned citizens, as well as technical and legal experts, Alberto started analysing the project in detail. They highlighted omissions and demanded additional studies to address the seismic risks, as the pipeline passes through one of the most active faults in Europe.

From this small group, the campaign spread across Puglia. Mayoral candidates stood on anti-pipeline platforms, and thousands of people attended a concert against the pipeline.

Photo by Laure Cops, Wouter Vanmol and Berber Verpoest.

“I felt we had to react, so I suggested organising our own festival,” says Treble, a reggae artist who lives in Melendugno. It was an instant success: “Over hundred artists registered to play for free and about 10,000 people came to party with us in August last year.”

At the other end of the pipeline lies Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. The city looks out onto the Caspian Sea, where the Shah Deniz ii gas fields are being drilled to feed the Euro-Caspian Mega Pipeline.

Pipelines and prisoners

Last June, I attempted to visit Azerbaijan during the inaugural European Games held in the capital Baku. I was detained and put on a plane back to London, the first of several unwelcome guests — Amnesty International and the Guardian were also barred from entering the country.

Those I travelled with to shoot Walking the Line managed to enter the country. Brand new stadiums, posters and video walls awaited them on their way from the airport to the hotel. Billions of dollars of oil money have been spent building new roads and glass skyscrapers.

Yet my companions soon discovered another side to Azerbaijan. Just a few kilometres from the centre of Baku, the six lane boulevards turn to dirt roads; the shiny 4×4 jeeps are replaced by Ladas and donkeys.

There are almost 87 political prisoners in Azerbaijan. They are journalists, bloggers, peace activists, human rights defenders and lawyers who have been arrested for speaking out against the corrupt Aliyev regime.

We managed to speak to the families of those we know in jail. People like Elmira Ismayilova whose daughter, the investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova, has been jailed for seven and a half years on false charges.

Ismayilova’s real crime was her journalism, which exposed the corruption reaching all the way to Azerbaijan’s president and his family. Elmira is proud of Khadija’s work, “I used to tell her to be careful, but never prohibited her from doing what she does. I think what she is doing is great and every citizen of this country should be doing this.”

Photo by Laure Cops, Wouter Vanmol and Berber Verpoest.

Khadija is an outspoken critic of the Aliyev regime and BP, the oil company they have worked hand in hand with since 1994. The British oil company has been the biggest foreign investor in Azerbaijan for over two decades after it became the operator of the largest oil field in the country. Today it is leading the consortium of oil companies involved in the Euro-Caspian Mega Pipeline.

Despite the deteriorating human rights situation, cooperation between BP and the Aliyev family has intensified over the years. The Aliyevs depend upon BP to maintain the flow of oil revenues to the state and the personal finances of the “first family”.

Khadija was clear about BP’s responsibility for human rights in Azerbaijan: “The Aliyev regime is good for BP. It allows their operations and they can sort out issues with the regime. Political influence is part of the bargain. BP is blamed for bringing Aliyev senior to power but it’s not just historic — the UK government is silent about problems with democracy in Azerbaijan. BP’s interests are dictating the agenda.”

BP are involved in every stage of the Euro-Caspian Mega Pipeline, they are determined that the gas they are extracting should reach a European market. In the process, they are ensuring the continuation of their successful relationship with the Aliyevs, and making the dynasty richer and more powerful.

Yet it is a rocky time for the BP-Aliyev alliance. The low oil price has seen both suffering economic misfortune — with half of Azerbaijan’s reserves being spent in one year, forcing the government into discussions with IMF to secure a $4 billion emergency loan package. BP hasn’t fared much better – reporting its biggest ever annual losses last month.

Such economic instability would throw an ambitious and expensive project like the Euro-Caspian Mega Pipeline into doubt if European public money wasn’t being used to underwrite the pipeline.

The western portion of the route, known as the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline, is slated to receive €2 billion from the European Investment Bank (EIB), the largest loan by the EU bank in its 57-year history. Another loan of €1 billion for the eastern part of the corridor through Turkey, the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP), is soon to be announced by the EIB.

Locked in

Gas is being sold to us as a clean fuel. But the reality is different: this pipeline will lock us into fossil fuels for the next fifty years and ensure our politicians continue working with repressive regimes like Azerbaijan.

The final place we visited for Walking the Line was a London estate. We went to Bannister house in Homerton where we met a community who, like the people of Puglia, want to take back control of their energy system. This community has put solar panels on top of every roof on the estate and set up a co-op. They collectively own the energy they produce, selling on what they don’t use and putting the money back into their community.

Photo by Laure Cops, Wouter Vanmol and Berber Verpoest.

The recent growth in community energy shows that we don’t need yet more import pipelines. Groups like Switched on London are calling for publicly controlled, renewable energy companies that can offer community energy co-ops secure contracts and sell electricity onto people at an affordable rate.

Whether it’s in Italy, Azerbaijan or the UK, people are fighting against the devastating impacts of import pipelines and wrestling back control over their energy system. By following the pipeline, we have been able to connect these stories — just as the extraction, pumping and burning of fossil fuels links us to places and people we know almost nothing of.

The European Investment Bank will be meeting this Thursday 10 March. You can tell the directors you don’t want our money spent on the Euro-Caspian Mega Pipeline.

Walking the Line is produced by Global Motion, Counter Balance, Platform and Re:common.

Never miss an update

We expose the risks of international public finance and bring critical updates from the ground – straight to your inbox.

Institution: EBRD | EIB

Theme: Energy & climate | Social & economic impacts

Location: Azerbaijan | Italy | United Kingdom

Project: Southern Gas Corridor / Euro-Caspian Mega Pipeline

Tags: Euro-Caspian Mega Pipeline | Ilham Aliyev | Khadija Ismayilova | Puglia | Southern Gas Corridor | democracy | human rights