The Romanian government is pursuing an increasingly contradictory energy strategy. On the one hand, it is preparing to heavily exploit Black Sea gas to increase consumption and drive industrial growth. On the other, it must meet ambitious targets for renewable energy, decarbonisation and energy consumption.

Raluca Petcu, Gas campaigner | 14 January 2026

These opposing policy directions have potential economic and environmental consequences. Increased gas consumption would result in higher energy costs for consumers and a rise in greenhouse gas emissions, while undermining government claims of improved regional energy security. Meanwhile, the expensive gas infrastructure currently being built in Romania with public funds will likely become ‘stranded assets’ in a future power market dominated by renewables.

Fossil gas remains the weakest link

The main reason the Romanian government is promoting higher fossil gas consumption is to offset the phase-out of the country’s coal-fired power plants. By 2030, the capacity of combined-cycle gas turbine (CCGT) power plants is expected to increase by at least 3.5 GW (1770 MW at Mintia, 850 MW at Ișalnița, 475 MW at Turceni and 430 MW at Iernut). Although no new capacity has yet been commissioned, some of these projects are already at an advanced stage of construction and could be operational as early as 2027.

In 2020, Romania had close to 4 GW of installed coal capacity. The planned replacement is therefore almost a one-to-one swap, even though the new gas-fired power plants are more efficient and could, in theory, produce the same amount of electricity with almost half the installed capacity. Romania’s strategy does not view renewables as capable of replacing coal facilities. The reality, however, is quite different.

After almost a decade of stagnation between 2014 and 2022 due to cancellation of the domestic Green Certificate scheme, renewables are growing again, albeit at a slow pace. The latest data shows that in 2023 the share of renewable energy reached 25.8% of final consumption, compared to 24.5% in 2020.

While the government is targeting a share of 38.3% by 2030 – corresponding to up to 10 GW of new capacity – this remains below the European Commission’s recommended target of 41%. New capacity, particularly from photovoltaic projects installed in 2024 and 2025, is expected to increase the share of renewables in the coming years, though the rate of growth must accelerate to meet national targets.

Romania’s national energy and climate plan sets a target for renewable power to account for 57.8% of consumption, up from 47.4% in 2023. However, the share of gas in the power sector is also projected to increase, from 20 to 24% by 2030.

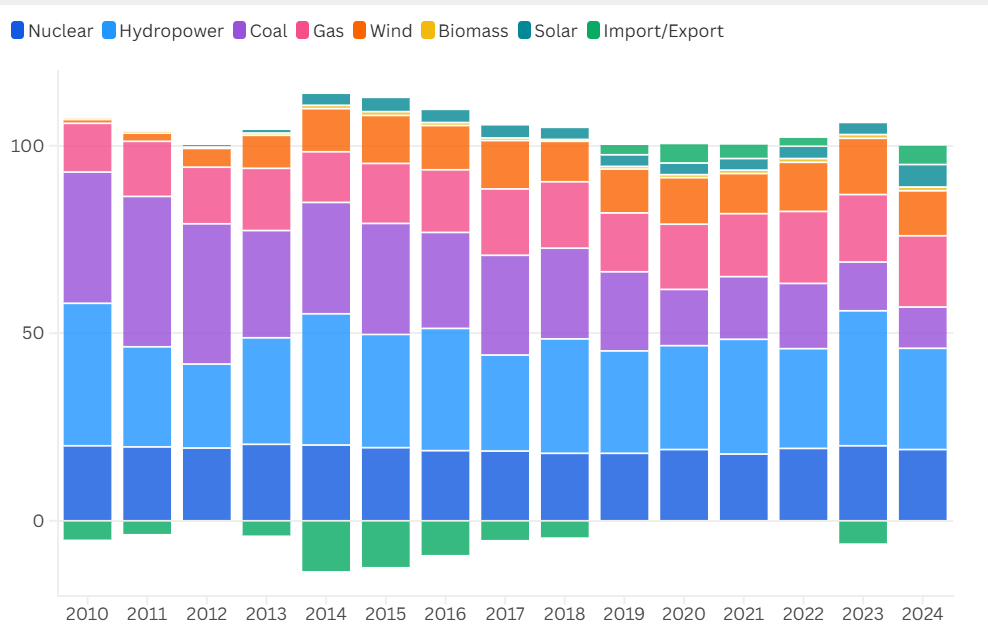

Since 2021, when the coal phase-out commenced, coal-based electricity production has declined by 4 percentage points, with wind and solar production increasing by 4.4 percentage points. Gas-fired power generation has remained largely stable, recording only minor variations of 1 to 2 percentage points and no change in installed capacity, with hydropower generation fluctuations dependent on water availability.

The chart below shows that renewables are already replacing coal-fired generation without the need for additional gas capacity. This transition can continue in the coming years, particularly if accompanied by investments in storage and network improvements.

The national energy and climate plan foresees a 12% decrease in primary energy consumption by 2030 compared to 2020. However, it also projects a 60% increase in electricity usage, from 55 to 80 terrawatt-hours (TWh) per year. By contrast, Transelectrica’s network development plan assumes electricity consumption will rise to only 60 TWh by 2030. Therefore, the plan’s projections do not align with expected electricity demand at the transmission level or with overall energy consumption.

If all the gas-fired plants are built and the targets for increasing renewable energy consumption are met, Romania may face overproduction relative to domestic demand. Theoretically, 3.5 GW of the gas-fired CCGT power plants operating at a 64% capacity factor could produce around 19.6 TWh per year, almost 50% more than the national energy and climate plan’s estimate of 13.5 TWh for all the installed gas capacity.

If Romania achieves its renewable energy targets, gas-fired power plants risk operating below capacity and incurring losses, given that clean sources are likely to assume market priority amid an abundance of renewable electricity. In this case, the new gas-fired power plants would likely need to rely on exports to remain competitive or require state aid to remain operational.

Romania has already invested over EUR 800 million from the EU’s Modernisation Fund in gas infrastructure, which risks becoming stranded assets. As a result, the country may increase its own emissions and use precious public funds to support decarbonisation elsewhere.

Domestic consumption or export?

The national energy and climate plan is also askew with projections from Transgaz, the national gas transmission system operator. While the plan foresees a small decline in fossil gas use, Transgaz estimates that consumption could double from 2027 onwards – an increase of over 10 billion cubic metres – under an optimistic scenario in which all gas projects are completed and operate at capacity. Besides electricity, Romania’s gas use in heating is also expanding significantly, with new district heating plants and distribution networks being supported with billions of euros in EU and national funds. Meanwhile, the government is encouraging industry to increase gas consumption, including gas extracted from the Black Sea.

The Neptun Deep perimeter is estimated to produce 8 billion cubic metres per year, which suggests this output alone would not be enough to cover domestic demand. Under these circumstances, Romania would have to import additional gas. Romanian decision makers have promised that Black Sea gas will strengthen regional energy security, with the Commission viewing it as a potential replacement for some of the gas previously supplied by Russia. OMV Petrom has already signed two sales contracts: one with Energocom in Moldova and the other with Uniper in Germany.

Romania evidently cannot double its gas consumption while securing gas resources for neighbouring countries. This raises questions about how Romania intends to honour national and EU commitments and whether it will ultimately become more dependent on gas imports in the future.

A costly pro-industry transition

Beyond the dilemma of ‘energy independence’, increased gas consumption would hinder decarbonisation of the energy sector and make the transition more expensive in the medium and long term, while also raising consumer energy bills.

First, additional gas consumption means more greenhouse gas emissions and higher carbon-allowance costs. From 2029, a carbon tax on buildings and transport is expected to come into force, placing extra pressure on households reliant on gas for heating. At an emission factor of 1.9 kilogram of CO2 per cubic metre of gas, doubling gas consumption would result in an estimated additional 19 million tonnes of CO₂ emissions, roughly twice as much as coal-fired power plants produced in 2020.

Second, gas drives up electricity prices because it often determines the marginal price in the power market. The goal should therefore be to reduce electricity generation from gas and decouple power prices from gas costs, rather than expanding gas-fired generation.

From 2035 onwards, hydrogen is set to be used in Romania’s new gas-fired power plants and within the national gas network once domestic gas resources are reduced. However, a market for renewable hydrogen does not yet exist globally and may never emerge despite all the bold claims and ambitious targets. Additionally, renewable hydrogen is likely to be far more expensive than previously estimated, making it unrealistic to expect it will ever compete with gas on price.

The broader costs of the transition must also be considered. Producing renewable hydrogen requires additional renewable energy capacity (currently not in place) as well as dedicated transport and storage infrastructure, on top of the investments already made in gas-fired power plants designed to consume hydrogen. This pathway is also highly energy-inefficient, given only one-third of the renewable energy produced would actually be consumed in gas-fired power plants.

This approach would also incur significant energy losses and require substantially higher investment than a transition to an electrification-based renewable system, which must be developed in any case. More public funds – impossible to estimate given the scale of investment required – would eventually be allocated to build hydrogen infrastructure and upgrade gas assets for hydrogen use. In practice, the public would end up subsidising the continued profitability of the fossil fuel sector at a much higher cost than a direct transition to sustainable renewables and electrification.

Swift action required

From a societal perspective, an energy transition based on fossil fuels is a losing proposition from the outset. High investment and operating costs, particularly in the context of a hydrogen-driven scenario, mean that gas-fired power plants risk failing to recover their costs, requiring repeated public bailouts. There is also a risk that operators will continue to run on gas, undermining the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Romania is over-investing in fossil fuel capacity, far exceeding its estimated consumption needs and renewable energy targets. This risks creating a market where production cannot be fully absorbed, leading to low returns on investment and a net loss for society. At the same time, the country’s push to increase consumption through Black Sea gas prevents the government from keeping its promises of regional energy security.

Romania needs a bold and consistent energy strategy that focuses on renewables, electrification, storage, and reduced energy consumption. This represents a significantly cheaper, faster and lower-emission decarbonisation pathway than parallel investments in gas and hydrogen.

Never miss an update

We expose the risks of international public finance and bring critical updates from the ground – straight to your inbox.