‘The stuff of fairytales’ is often what people say when they hear commoner-to-princess stories like those of Kate and Meghan, witness the Northern Lights, or marvel at Leicester City winning the Premier League in 2016.

But it’s definitely not the phrase you want to hear when it comes to the EU’s funding priorities for the energy transition. And yet a Bankwatch report released last week reveals that, in 2024 alone, the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) – a key EU energy infrastructure fund – sunk EUR 454 million into fantasy energy technologies like fossil gas-sourced hydrogen with carbon capture.

Public funding props up fantasy fuels

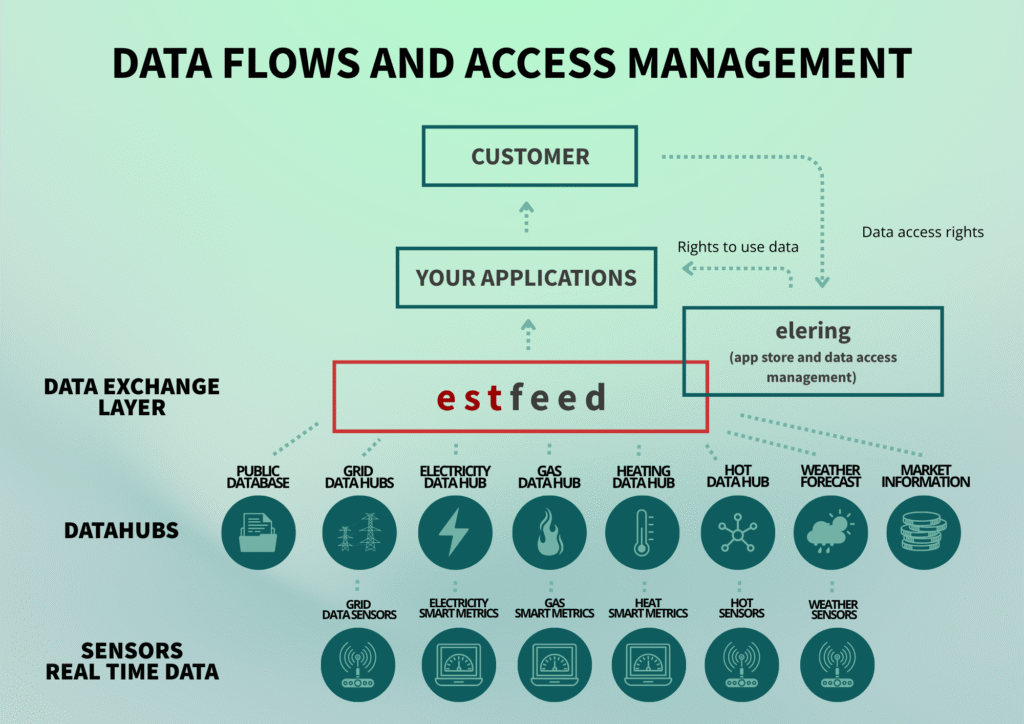

Since it was established in 2024, the CEF has been heavily financing projects that have very little to do with climate action and everything to do with the survival of the fossil-fuel industry. Yet this substantial outlay could have been invested in proven and mature solutions such as electricity interconnections, smart grids, and grid flexibility.

According to both the International Energy Agency and the International Panel on Climate Change, investments in renewables, energy efficiency, and electrification, combined with cuts to fugitive methane emissions, have the potential to meet over 80 per cent of the world’s decarbonisation needs by 2030. Yet while Europe’s electricity grids are in desperate need of funding to the tune of almost EUR 600 billion, the CEF is betting EU money on all the wrong kinds of energy projects under the guise of the energy transition.

Hydrogen produced from fossil gas with carbon capture has a negative climate impact, largely due to its lifecycle methane emissions and the cost and inefficiency of carbon capture technologies. In fact, their combined track record is distinctly unimpressive. By 2022, after decades of research and public funding, carbon capture and storage had sequestered just 0.1 per cent of global energy-related carbon dioxide emissions. Today, 99 per cent of hydrogen produced globally still comes from fossil fuels. These technologies are not the answer to Europe’s liveable, climate-resilient future.

No matter which way you slice it, carbon capture is not a commercially viable solution for reducing carbon emissions, and its actual impact is negligible compared to the vast swathes of public money it’s already managed to capture.

Industry interests and the competitiveness myth

These glaring failures should matter deeply to the European Commission, which seems intent on adhering to the new Brussels dogma of ‘security and competitiveness’. Yet fossil gas-based hydrogen and carbon capture – both fully endorsed by the Commission – fail the competitiveness test spectacularly. Carbon capture projects routinely underdeliver, with most only operating in the context of fossil-fuel processing or production, which ultimately defeats the very purpose of decarbonisation.

What’s more, the financial ramifications of the hydrogen and carbon-capture hype for citizens has been blatantly ignored. Our analysis shows that the main beneficiaries of CEF funding are gas transmission system operators and fossil-fuel giants like Shell, Equinor and Eni.

These industry heavyweights have long lobbied aggressively for false solutions and greenwashing tools that waste precious financial resources. And it’s no surprise how we got here. The oil and gas industry held close to 900 meetings with Von der Leyen’s cabinet during her first term between 2019 and 2024. In fact, the industry spent a whopping EUR 75 million each year on lobbying during this period.

Even more concerning is the central role played by the gas lobby – represented by the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas (ENTSOG) – in shaping EU energy planning. ENTSOG – an industry group comprising the very companies that profit from transporting gas between EU Member States – is now trying to replicate their tried-and-tested model with hydrogen. The bigger the hydrogen network, the more these operators stand to gain.

Additionally, the repercussions of the Clean Industrial Deal on future funding for hydrogen and carbon capture will reveal just how ugly this story could become. Launched by the Commission in February 2025, the Deal is set to result in loosened regulations and increased money flows to these technologies, which would represent a major loss for climate. And the warning signs are already visible in the Commission’s current draft of the Low-Carbon Hydrogen Delegated Act – a key component of the Deal – which sets criminally weak standards that fail to limit methane emissions.

Will the EU fund a sustainable future?

Publicly funded decarbonisation projects must serve the public interest. They should also be functional, efficient, and effective. Instead, the EU’s current strategy is designed to subsidise the already ridiculously wealthy fossil-fuel industry by supporting their greenwashing efforts. Meanwhile, as the EU struggles to reduce emissions from the energy sector, over 1,700 gigawatts of solar and wind power across Europe awaits connection to the grid.

More promisingly, the upcoming EU grids package, expected by the end of 2025, provides a crucial opportunity to fix these issues. But it will only succeed if lawmakers put down the axe when it comes to environmental rules. We already have the solutions. Now we just need to fund them.

The EU must mobilise and direct its resources to develop a renewables-based, flexible, and smart electricity grid without destroying nature or undermining the hard-won environmental safeguards that protect it. But above all, it must stop subsidising fossil fuels. Otherwise, reaching the ambitious 2030 climate goals will remain a costly pipe dream.

Plans without protections

Plans without protections