Shell’s new shale gas frontier in Ukraine: another fossil fuel opening for EBRD?

Bankwatch Mail | 7 March 2013

The industry frenzy surrounding the development of shale gas in Europe is gathering pace, with the announcement in late January of a EUR 400 million deal between Shell and Ukraine to develop the country’s shale gas potential.

This article is from Issue 55 of our quarterly newsletter Bankwatch Mail

Browse all articles on the right

However, the debate over the future of shale gas in Europe is anything but static. While the Ukraine deal may have provided fossil fuel proponents with some bragging rights, just a few weeks later Germany’s upper house of parliament passed a resolution urging the German cabinet to tighten regulations for hydraulic fracturing (or ‘fracking’) in Germany.

Across the length and breadth of Europe, from the UK to Ukraine, we are seeing a tit-for-tat battle between shale gas prospectors salivating over new reserve finds, national parliaments that have been issuing shale gas moratoria and local communities clearly very concerned about the general disruption and environmental havoc that shale gas exploitation has brought to so many places across the US.

Ukraine’s renewable potential

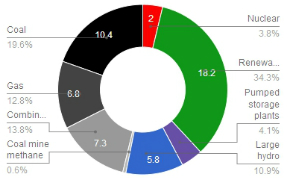

According to our estimations, Ukraine could cover up to 27 per cent of its electricity demand in 2030 with renewable energy.

A telling tweet from Terry Macalister, the Energy editor of The Guardian newspaper, goes a long way to explaining what is playing out as the fossil fuel industry attempts to make the case for its latest strand of financial life support. According to Macalister, tweeting on December 13 last year: “In two decades I have never come across such heavy lobbying than for shale gas. What a pity renewables cant get that financial muscle.”

Joining the fray in its own special way, and following the January announcement of the Shell and Ukraine’s shale gas deal (Chevron has also signed shale gas contracts with Ukraine recently), was the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. In a Financial Times blog post, the EBRD’s managing director for energy and natural resources, Riccardo Puliti, reacted to the Shell-Ukraine shale deal with what appeared to be an expression – albeit a circumspect one for now – of the development bank’s interest in becoming involved in Ukraine’s potentially burgeoning shale gas sector.

In his article, Puliti, curiously also a member of the supervisory board of OMV Petrom SA, Romania’s biggest oil company that is said to be assessing that country’s potential for shale gas development, does point to the environmental concerns involved in Ukrainian shale gas development and the recent Shell deal: “There is vocal environmental opposition to the development of shale gas resources in Ukraine but, by and large, the deal was perceived a success.”

Not surprisingly, the article does not linger long on such concerns – Puliti’s prime focus is on the potential for shale gas to be a game-changer for Ukrainian energy supply and independence, and on the investment opportunities. While not a clear declaration of intent from the EBRD, nonetheless Puliti’s sentiments represent the first public expression of at least vague interest from an international financial institution in European shale gas.

Why should this be an issue of concern? There are a string of reasons but mention of just a few will suffice for now.

For one thing, the environmental opposition to shale gas in Ukraine, largely glossed over by Puliti, is founded on some stark realities, including the location of shale reserves in protected nature areas and seismically active zones. Most worryingly at the present time is the fact that Ukraine’s environmental impact assessment (EIA) regime has no teeth under current legislation: exploitation projects in Ukraine do not require EIAs. If the EBRD chose to get involved directly in a shale gas project – and this could take several years to materialise, as we are only at the assessment stage right now despite the industry hoopla – the bank could argue that it would demand the upholding of European environmental standards. The same was true of the Sakhalin II oil and gas project, though at the time of its pull-out from that controversial project in 2007, the EBRD had not been in a position to grant final environmental approval to the project promoters. This was in spite of the project’s long implementation period that had been said to involve ‘cutting edge, western standards’. Said project promoter at the time was Shell.

If EBRD – and it would be a shrewd move, given historical experience – opts not to involve itself in the hard end of project finance for shale gas projects in Ukraine (or elsewhere), it may of course line itself up to be a financial accessory to the industry as a whole. As Puliti points out, “Once (legal and regulatory) change starts to happen, mid-sized companies will follow the big boys and help Ukraine bring real energy independence closer.” This could well be the biggest risk for those who believe that an international public bank, drawing on the taxpayer contributions of countries across the world, should not be dragging resources that could be deployed for much needed clean energy projects into ‘below the radar’ support for the fossil fuel industry.

Ultimately, arguments against the EBRD – and other IFIs such as the EIB – supporting shale gas may boil down to fundamental banking rationales that environmental campaigners have often found themselves at the sharp end of when trying to persuade the IFIs not to fund climate-damaging investments: namely, ‘bankability’.

For a variety of reasons including differing geological and infrastructure conditions, shale gas exploitation in Europe is regarded by potential investors as being economically unpalatable, certainly when compared to the US experience. According to a Deutsche Bank analysis published last year, European shale gas will cost twice as much to produce as US shale gas. The German bank has let it be known: “Those waiting for a shale gas ‘revolution’ outside the US will likely be disappointed, in terms of both price and the speed at which high-volume production can be achieved.”

The logic of banking principles may sometimes be hard to fathom, but it would certainly be more unfathomable to see the EBRD backing a loser such as European shale gas. Or is the bank now giddy about extending its fossil fuel subsidies, beyond all reasonable environmental and economic logic?

Never miss an update

We expose the risks of international public finance and bring critical updates from the ground. We believe that the billions of public money should work for people and the environment.

STAY INFORMED