From grassroots activism to fighting Goliath

Bankwatch’s 30-year quest for just and sustainable public finance

3 June 2025

Story by Magdalena Wiejak & Dora Crnčević, Communications officers, Bankwatch

From grassroots defiance to a force for accountability, Bankwatch’s story begins long before its founding in 1995. Amid collapsing regimes, our network channelled the energy of civil resistance into a brave new experiment in public oversight and transparency.

Challenging powerful institutions like the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the European Investment Bank, and the World Bank, Bankwatch emerged as a reliable and determined counterweight to unchecked development.

This is the story of how a modest gathering of like-minded activists became an unstoppable movement for change – and why its mission remains more urgent than ever. For people and the planet!

The fall of the Berlin wall and the rise of civil society

Though Bankwatch was formally established in 1995, the seeds were sown long before that moment. It’s important to remember: civil society in central and eastern Europe didn’t magically spring to life after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Within the diverse political landscapes of the Eastern Bloc, grassroots movements – environmental ones included – found ways to exist, however constrained. The space to speak out was narrow, but the spirit of resistance and self-organisation had already taken root.

With the collapse of communist regimes came a breath of fresh air, carrying with it new freedoms and a flood of possibilities. Across the region, activists – many of whom had long worked under the radar – began looking outward, seeking solidarity and a shared strategy. The challenges were remarkably similar across borders: transitioning economies, fragile institutions, and a sudden influx of Western capital. And it was precisely for this purpose that the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) was born in 1991 – to help former communist states shift from centrally planned economies to market-oriented systems and integrate with the West.

But from the outset, the question was never simply about accessing money – it was about how that money would be spent. Development finance has a long, chequered history of rushing into regions with investment plans that lack both local insight and proper due diligence. Too often, these projects reflect a top-down, neo–colonial logic. That’s why the role of civil society – serving as a counterbalance, a watchdog, and a voice for affected communities – has always been essential.

There’s a saying that ‘all roads lead to Rome’. However, in Bankwatch’s case, all roads led to Ludwigsburg, Germany. It was there, in 1994, that a training session helped ignite what would become a powerful transnational movement. The event, organised by Western environmental civil society organisations, was titled ‘The World Bank – A Chance for the Environment in Europe?’ It brought together activists from across central and eastern Europe to explore the link between public finance and environmental justice. It was the first time that many of these activists stood in the same room – unaware that just a few months and a handful of training sessions later, they would establish a network that would still be thriving three decades on.

Jim Barnes, the director of Friends of the Earth International Department at the time, was among the trainers. With deep roots in environmental advocacy and possessed with a gift for building movements, Jim played a pivotal role in what came next. He would go on to serve as an advisor and board member of Bankwatch for over a decade. When asked today whether he imagined back then that the network would last this long, he smiles:

‘I knew it from the beginning because I thought these were interesting people and I enjoyed working with them and I liked a lot of their ideas so I knew we could do some good projects. There were numbers of people who, in their own way, made a real difference with certain parts of Bankwatch and how we worked.

I believe almost everybody who’s ever touched Bankwatch and tried to help it in some way has come away thinking how this is a really special group of people who really think carefully about things that most people are casual about. For me, it’s been fascinating to watch how everything has evolved over all these years.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, there were all these young people who were now free to do whatever they wanted to do. It was like the curtains had been drawn, finally allowing you to see the full play. A lot of it was hidden before, so in a way, the door was wide open because the kids – I call them kids because I’m just older than most of them were then – they suddenly had so much freedom.’

It was thanks to Jim’s tireless efforts – and his extensive connections within the international donor community – that the fledgling project secured enough funding to run for three full years. But no one ever said that three years would be the end of the story.

In 1995, the founding meeting took place in Kraków, Poland. Around the table sat Helga Cukure (Latvia), Linas Vainius (Lithuania), Peep Mardiste (Estonia), Pavel Pribyl (Czech Republic), Jozsef Feiler (Hungary), Norbert Brazda (Slovakia), Macrin Desa (Romania), Tomasz Terlecki (Poland), Magda Stoczkiewicz (Poland), and Jim Barnes. Together, they officially established the Central and Eastern European Bankwatch Network. The logo? A simple hand sketch by Peep on a scrap of paper, later immortalised in Microsoft Paint!

The mission to monitor public finance and challenge harmful lending practices emerged naturally. In the early days, Bankwatch focused on projects that touched people’s daily lives, such as investments in transport, waste, and other basic infrastructure. Again and again, these projects overlooked environmental safeguards, disregarded community impact, and prioritised profit over sustainability.

From Jim’s perspective, the initial drive was to create a self-determined organisation:

‘It was clear that all these people from eastern Europe wanted to have a network that was housed in eastern Europe and that was run by people from eastern Europe. There were all these different countries who had various needs – some were different but some of the needs were exactly the same, especially procedural aspects, democratic aspects, and so forth. Bankwatch has done a great job fulfilling a vision that these people dreamed of from the very beginning. They wanted the network to be homegrown and rooted in the realities of the people.’

If international institutions wanted to invest in the region, the people had a right to be informed – and involved. That principle became a cornerstone of the movement. Right from the outset, Bankwatchers showed up at the annual meetings of international financial institutions, made their presence known, and brought crucial national and regional concerns to the global stage.

But that was just the start.

The watch begins

In May 2000, the Bankwatch team embarked on its very first fact-finding mission – an exploratory journey across the three Baltic states. The occasion was fitting: Bankwatch was celebrating its fifth anniversary. For many of the participants, including some from the Baltics themselves, this was the first time they had set foot in all three countries. It was a trip on its own, travelling through the eastern landscape at 40 km/h in an old train with a samovar in each compartment and a lady cooking borscht for lunch. Just a decade earlier, this type of travel had been restricted by the barriers that had only begun to fall after 1989.

The trip served a dual purpose. On the one hand, it was a diplomatic tour: an opportunity to meet government officials and introduce our work. But in Tartu, Estonia, over 30 people, many of them new young Bankwatchers, had an opportunity to hang around together and exchange ideas.

That same year, Bankwatch began monitoring EU funds, even though none of the countries in which the organisation operated were Member States at the time. Many of them, however, were receiving support through the Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance (IPA) – a form of financial aid designed to prepare them for eventual EU membership. Recognising the importance of this funding, Bankwatch began monitoring how IPA money was being spent across at least six countries. Our first major publication on the subject posed a provocative question: ‘Billions for sustainability?’ The question mark was intentional. While the sums involved were significant, the types of projects being funded – highways, incinerators, airports – raised doubts. Were these truly the kinds of investments that would support central and eastern Europe in aligning with EU environmental standards? Or were they simply large-scale infrastructure projects with questionable benefits for people and the environment?

Together with Friends of the Earth Europe, Bankwatch started a campaign to dig deeper. In Brussels, Magda Stoczkiewicz led the campaign and coordinated advocacy efforts at the EU level. By the end of 2000, Bankwatch had released its first critical report on the spending of IPA funds and organised its inaugural advocacy week. The report struck a nerve – at the time, hardly anyone was scrutinising EU funds, let alone the way they were being spent in future Member States.

Bankwatch began asking uncomfortable but necessary questions. Why were non-governmental organisations being excluded from the decision-making process? Why were these decisions being made behind closed doors? With time, pressure began to pay off. Surprisingly, some Member States responded by forming monitoring committees, inviting Bankwatch to the table. And while the invitations weren’t legally binding, they marked a vital first step in gaining a voice in EU funding decisions.

The year 2004 marked the EU’s fifth and largest expansion, with more countries and people joining than ever before, including Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Three years later, Bulgaria and Romania would also join.

During this accession process, Bankwatch played to its strengths by leveraging EU legislation as a primary tool to hold governments accountable – particularly for their failure to implement the Environmental Impact Assessment Directive. Accession countries were already bound by several international conventions that paved the way towards EU legal alignment. One notable example was the Bern Convention, which required countries in central and eastern European countries to assess and protect areas rich in biodiversity.

From the outset, direct contact with the European Commission proved crucial to Bankwatch’s strategy. By bringing intelligence from the ground, we served as a reliable source of information on local government plans, potential project alternatives and, at times, perspectives that contradicted the official narrative. To give some context, the EU’s primary focus at the time was on disbursing funds as quickly as possible while ensuring that countries had the capacity to absorb them. In those early days, quantity was more important than quality – the prevailing approach was to dole money out, with little consideration given to how it was actually spent.

It became quite obvious early on that Bankwatch’s role would extend far beyond simply monitoring the banks. Oversight of public capital, particularly EU funds, would need to be just as important. As a result, monitoring and advocacy around EU spending became part of Bankwatch’s daily work. Years of campaigning eventually led to a shift in focus, with increasing recognition that the quality of EU spending is just as important as the quantity.

Fighting for people, not just the environment

Engagement in various development projects quickly clarified Bankwatch’s priorities: its focus was never solely on the environment in isolation. Large-scale investments in economically developing countries almost invariably have direct and profound impacts on the communities they touch.

In the late 1990s, Manana Kochladze, a young Georgian activist then working for her local Friends of the Earth branch, participated in a number of trainings. It was during this period that she encountered Bankwatch and became familiar with how we worked. Our approach to activism resonated deeply with her. Having worked closely with local communities, she possessed a clear understanding of what was at stake when powerful financial institutions became involved. The core challenge was to elevate the concerns of ordinary people to those in positions of power, and to advocate for meaningful influence.

Such was the case with the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan (BTC) oil pipeline project, a major initiative supported by the World Bank, the EBRD, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), and others.

The pipeline was heralded as a pathway to numerous benefits: reduced dependence on Russian energy, strengthened relations with the West, and support for democratic development in post-Soviet states. Western investment of this magnitude was largely welcomed by the local population, accompanied by a strong political narrative that framed the project as a strategic necessity. As a result, despite its environmental costs, there was little serious effort to stop the BTC project altogether. Throughout, Bankwatch’s guiding principle remained constant: to first listen to those directly impacted, to understand the full context, and then to offer support based on a comprehensive assessment.

Indeed, many communities in Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey initially greeted the project with optimism. The pipeline was seen not only as a means of transporting oil, but also as a symbol of freedom, economic opportunity, and integration with the West. People hoped for new jobs, fair compensation for land use, and the development of essential infrastructure. After all, the pipeline would require construction, operation, and management. Revenues from oil exports promised a brighter future. However, large investments carry corresponding responsibilities – responsibilities that the financial institutions involved failed to adequately consider.

From its inception, the project was fraught with issues, particularly those related to human rights. Beyond the very real risks of environmental degradation, the BTC pipeline had severe and often overlooked consequences for local populations.

The post-Soviet transition was uneven and marked by hardship. Poverty remained widespread, especially in rural areas, and the communities directly affected by the pipeline had next to no input in determining its route or anticipating its impact. In some instances, villagers discovered that a massive pipeline had been laid through their own backyards without any prior warning or consent. Resettlement – always a politically and socially sensitive matter was generally avoided. Nonetheless, the project proceeded, often at the expense of community safety, primarily due to the use of outdated infrastructure that was known to be prone to leakage.

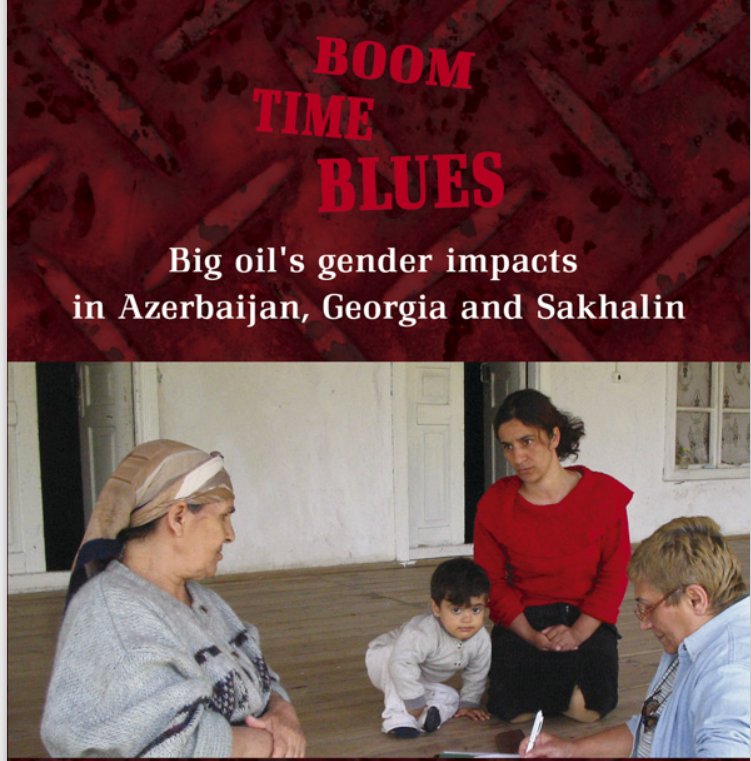

It may seem reasonable to assume that development projects would create employment opportunities. In theory, yes – but only if implemented responsibly. In practice, however, the pipeline project led to a gendered division of labour that went largely unacknowledged. Men from rural areas left home to work on construction sites, leaving women to take on multiple roles as caregivers, educators, farmers, and household managers – carried out without any support. The gender dimensions of the project had had been completely neglected during planning.

In addition, the emergence of isolated work camps brought new risks. Many of these settlements became sites of gender-based violence, exploitation, and trafficking. Instances of forced sex work and sexual harassment along the pipeline route increased. Women employed by the project were typically hired as cooks or cleaners under short-term contracts that frequently violated labour standards. Far from advancing gender equality, the BTC pipeline exacerbated existing inequalities and introduced new vulnerabilities.

This ill-judged project – and many others funded by public financial institutions – underscored the urgent need for reform, illustrating how unchecked investment, without robust due diligence, can cause lasting harm to both people and the environment.

Bankwatch submitted numerous formal complaints, detailed reports, and public statements in an effort to mitigate the project’s negative impacts. Despite these efforts, the pipeline was completed. In October 2005, the 1,768-kilometre BTC pipeline began pumping oil. Over time, it would come to be seen as a cautionary example – a case study in how not to reduce poverty through development finance.

Nonetheless, our advocacy efforts did not go in vain. What once seemed like an exercise in futility in the early 2000s has slowly shifted institutional practices. Consider, for example, the increased attention to gender in development financing. The visible consequences of the BTC pipeline, alongside the sustained pressure from civil society organisations such as Bankwatch, compelled institutions to update their policies. Both the World Bank and the EBRD now maintain gender equality strategies, which would not have been introduced without the testimonies from villagers in Georgia and Azerbaijan.

Manana – now Bankwatch’s Democratisation and Human Rights Strategic Area Leader – reflects on how the banks’ approaches to human rights have evolved over time:

‘Looking back, it’s clear we’ve come a long way in terms of recognising the human rights impacts of development finance. Today, many banks conduct human rights assessments at the country level before moving forward with major projects. One example that comes to mind is the World Bank’s decision in Uganda. When one homophobic law was introduced, the bank issued a clear statement – it publicly declared that, due to this legislation, it would withhold funding from the country. It doesn’t matter that the decision comes from an international financial institution – it’s a political move and the kind of intervention that can create a backlash.

Many governments in the Global South have bristled at what they see as external interference: “Who is the World Bank to tell us how to govern our countries?” they ask. Yet, the foundation for our advocacy remains strong: international human rights law exists, and it should be respected, regardless of borders. Over time, human rights have become more than a side issue; they are now an important element in the global development conversation. But the challenges haven’t disappeared – they’ve simply evolved. The rise of anti-gender movements and shrinking civic space are no longer confined to faraway places like Central Asia, Africa, or the Caucasus. Even within the EU, governments are clamping down on civic freedoms and rolling back on human rights protections.

So, on the one hand, the banks are increasingly aware of their responsibility to protect human rights. But on the other, they’re seeking to expand their operations, even in countries where democracy is hanging by a thread. That contradiction remains at the heart of our work: pushing for stronger safeguards in a world where political and financial interests often pull in the opposite direction.’

It remains unfortunate that meaningful reform is often preceded by significant harm. It can be frustrating to campaign for years before any visible change takes place. And yet, the effort is worthwhile – not only for the environment, but equally for the people whose lives are so deeply affected by these projects.

Manana adds:

‘Our advocacy journey has rarely been straightforward. Each encounter, each meeting, depended on the specific institution, the department and, more often than not, the individuals in the room. I can recall meetings where high-rank officials were screaming at us, frustrated that we refused to embrace the huge benefits of a project, choosing instead to highlight its flaws and question its long-term consequences. To them, we were complicating their lives; but to us, they were overlooking the people most affected. But it wasn’t all resistance.

Along the way, we met allies – individuals inside the system who understood the deeper value of what we were doing. They didn’t just nod and move on. Some brought our concerns forward, influencing internal discussions and even policy directions. A few pushed for new forms of advisory support that would give space to voices like ours and help shape more responsive, inclusive decision-making.

At the end of the day, I believe that working on something is better than giving up – simple as that. Whenever you see the possibility to change something on the ground, you need to do it. For me, this groundwork approach is very important – having good relations with the locals and helping them stay strong.’

Power to the people, not to the banks

One might ask – what’s the point? Why try to sway the decisions of those with such immense power? After all, we’re talking about millions – sometimes billions – in public funds. But the key word is public. This isn’t some distant, abstract wealth; it’s ours. The capital these banks invest, the loans they grant, the infrastructure they bankroll – it stems from our taxes, our markets, our collective labour. It seems only natural that we, the public, should have a voice in how it’s spent.

Today, that idea might feel self-evident. But 30 years ago, it was far from mainstream. Back then, international financial institutions – aloof and fortified behind bureaucratic walls – were scarcely aware of civil society, let alone interested in engaging with it. Environmental activists had to stay persistent to pry open those doors, demanding not just entry, but a seat at the table.

And even now, the struggle continues. Many public development banks still cloak their operations in opacity, financing projects that endanger ecosystems and communities alike. Basic transparency remains elusive. Public consultation is too often an afterthought. Risk assessments are skipped. And money flows – unchecked – into ventures with the power to irreparably scar the planet.

Take the European Investment Bank (EIB). Once criticised for its secrecy, it took years of tireless advocacy – especially from Bankwatch – to force a shift. In 2004, under mounting pressure, the EIB published its first Transparency Policy, and later that year, launched a Public Information Policy with public consultation, something we had urged them to do for years. Fast forward, and the Bank now proudly calls itself the EU’s ‘climate bank’. A bold title, but earned slowly. It wasn’t until 2019 that the EIB officially pledged to stop financing fossil–fuel projects, with the policy taking effect in 2021. It took a full quarter of a century for one of Europe’s most powerful financial institutions to acknowledge what by that time 90 per cent of the world’s climate scientists had already concluded: fossil fuels are a dead end.

In the face of runaway capitalism and escalating climate collapse – and as some political leaders backpedal from the Paris Agreement to chants of ‘drill, baby, drill’ – it’s easy for activists to feel overwhelmed. It’s David versus Goliath, day after day. Why would bankers care about fragile ecosystems, rural communities, or the future of a liveable Earth when pipelines and excavators promise short-term profits and safe returns?

And yet, David didn’t need brute strength to defeat Goliath. He needed strategy. Ingenuity. Courage.

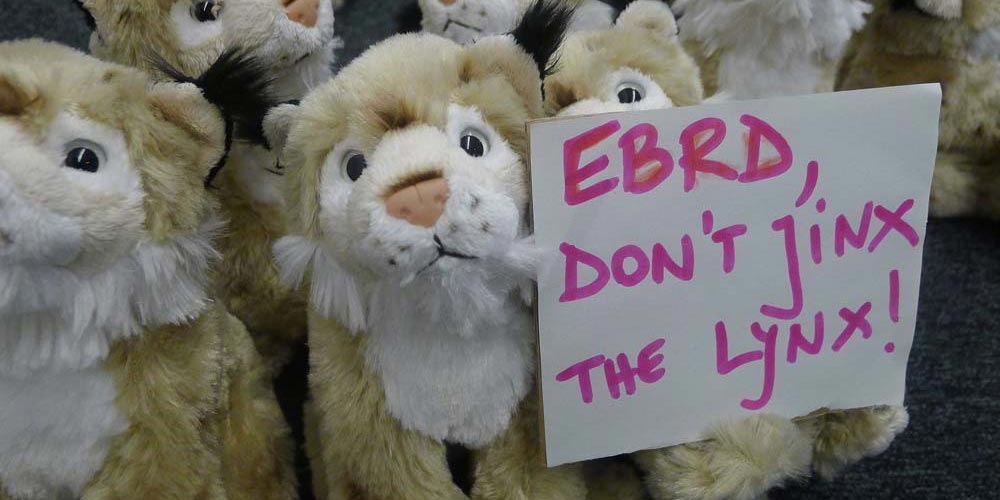

In 2010, such a strategy emerged in the fight to save Macedonia’s Mavrovo National Park, a sanctuary home to the critically endangered Balkan lynx. The World Bank considered a USD 70 million loan, and the EBRD pledged EUR 65 million, to build two hydropower plants within the park. The threat to wildlife, water systems, and biodiversity was immense. Yet in 2011, the EBRD approved its loan before conducting an environmental and social impact assessment – a blatant violation of its own policies.

Our Macedonian colleagues at Eko-svest acted immediately. They filed a formal complaint. They rallied local communities. Scientists joined the cause, with a 200-strong coalition petitioning the Macedonian Prime Minister. Protests erupted outside the World Bank office. A complaint was submitted to the Bern Convention. Years of relentless effort finally bore fruit: the financial institutions backed down. The dam projects were shelved. And the fragile ecosystem of Mavrovo was spared.

That victory, like so many others, wasn’t the result of a lone voice shouting into the void. It was the product of organised resistance, deep networks, and shared knowledge. That’s how Bankwatch was born, and that’s how it still thrives.

Every campaign is a reminder: it’s not only about stopping a single harmful project. It’s about rewriting the very idea of development – ensuring that investment serves people and the environment, not just profit.

Take, for instance, our work in Poland. For seven long years, we campaigned alongside Polish activists and our member group Polish Green Network to protect the Rospuda Valley – an untouched peatland haven in the country’s northeast – from an EU-funded road project that would have carved through its heart. It was a battle of endurance. But in 2009, we won. The Via Baltica route was changed. The valley remains wild.

These are the stories that remind us: the impossible can become real. David can conquer Goliath. And sometimes, with enough voices, enough courage, and enough persistence – the underdogs win.

Turning crisis into opportunity

For years, climate activists raised their voices – urgently, persistently – but their warnings fell on deaf ears, as world leaders and politicians turned away from the growing signs of ecological catastrophe. The evidence was there: the slow unravelling of ecosystems, the growing unease among scientists, the uncomfortable realisation that our home, planet Earth, was slipping into crisis. Yet it wasn’t until 2016 that the world finally stood still long enough to listen.

That year marked a historic turning point. In an unprecedented show of unity, 195 nations came together to sign the Paris Agreement – an international treaty aimed at curbing climate change. Its goal was ambitious yet clear: by 2030, global carbon dioxide emissions must be cut in half to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. A number that might seem small, but in reality, carries catastrophic consequences for countless species and millions of human lives. The agreement was hailed as a breakthrough – a long-overdue acknowledgment by world leaders of one of the most pressing existential threats of our time.

And yet, ambition did not translate into action.

Despite the signatures and speeches, emissions continued their relentless climb. Each year hotter than the last, with 2024 the warmest yet. The planet kept heating. The crisis kept growing. And in response, the voices of climate activists only grew louder, more urgent, more relentless in their pursuit of justice for the Earth.

The movement surged. From Stockholm, Greta Thunberg’s solitary school strike blossomed into a global phenomenon, inspiring millions of young people to walk out of classrooms and onto the streets. Each new IPCC report sounded the alarm with increasing urgency. Cities filled with peaceful protests – hand-painted signs raised high, chants echoing calls for a liveable future. The Conference of the Parties (COP) meetings became rallying grounds not only for delegates, but for demonstrators determined to show that the so-called ‘stakeholders’ weren’t doing nearly enough.

Momentum was building. There was hope. A feeling that together – through networks, communities, and mass mobilisation – change was not just possible, but inevitable. That political will could be forged by a collective voice. That time was short, but not yet lost.

And then, in 2020, the world fell silent. A virus swept across continents, halting travel, shuttering gatherings, turning connection into contagion. COVID-19 forced the climate movement to pause, just as its momentum was peaking. Networks frayed. The fight was temporarily eclipsed by the immediacy of a new crisis.

Anelia Stefanova, our Energy Transformation Strategic Area Leader, reflecting on those turbulent years, acknowledges the weight of that setback. The pandemic was a blow – not only to logistics, but to spirit. And yet, she speaks not of despair, but of resilience:

‘I notice that working together, collaborating, and strategising is getting more “trendy” in Brussels again, but I would say we’ve still a long way to go before we get back the momentum we had before COVID hit. What’s needed now is to rebuild strong social and environmental coalitions, and just as importantly, pass on the spirit of campaigning to younger generations. One challenge I see is the constant turnover among young people in the movement. Many see their time in environmental groups as a stepping stone to careers in government or academia. That’s not their fault but rather a reflection of how our movement struggles to offer long-term purpose.

That’s why we need to cultivate a culture of long-term commitment and to equip our teams with the tools and arguments to take on our most pressing challenges and face adversity with courage on a daily basis. We need to be strongly aligned with our values. If we surround ourselves with people who share the same vision, and they support us but also tell us where we could do better – it creates an internal source of hope.

I don’t have a golden ticket, but I am a very optimistic person, so I never allow myself to lose hope. I believe in the power of creativity and unexpected action to create a spark. Real change often comes not from sudden revolutions, but from steady, collective pressure over time. We must keep finding new ways to provoke different attitudes or mobilise hidden allies.’

And within that belief lies Bankwatch’s guiding strategy: Rebuild. Reconnect. Start small. In communities and collectives. Take steady steps in the right direction. Support each other locally to make change globally. That’s where she sees true power. That’s also where Bankwatch – an environmental watchdog network – finds its strength.

As Anelia recalls, Bankwatch began like a family. Small. Passionate. Interconnected. And even amid the pandemic, it chose not to contract in fear but to grow in faith. With travel on pause and budgets reallocated, the organisation doubled in size, investing in its people – the most valuable asset any movement can have.

‘I think it’s important that we always look for the opportunities, even in the midst of crisis. For instance, what I recall from the time of the financial crisis is that, while most people were focused on economic collapse, we saw a chance to shine a light on the hidden world of development banking, particularly the EIB, which had long operated with little transparency or accountability. And the timing was right: the crisis had raised public scepticism about financial institutions. We seized the moment and managed to make the EIB accountable to the European Ombudsman with our “Right to complain.” campaign.

But we didn’t stop there. We knew we had to be visible and a bit provocative. In Luxembourg – the quiet seat of the EIB – we staged creative actions designed to grab attention. One of our most effective interventions was to fill a popular Luxembourg newspaper with fictional headlines about the EIB suddenly going green, prioritising people over profit. We handed it out right in the city’s main square, and even delivered a public speech to people passing by. What did we achieve by doing that, you might ask?

People inside the bank actually loved it. Some staff shared our concerns and felt heard for the first time. Suddenly, doors began to open – quiet meetings, document leaks, and subtle shifts in attitude. Our campaign had struck a nerve not just outside the bank, but within it. Also, having an ambitious climate agenda is a huge advantage. Initiatives such as the European Green Deal and Fit for 55 are important for our work.

But now we’re going even further by questioning whether these ambitious climate goals are negatively impacting the social aspects, the economy, competitiveness, and so on. The answer lies in how the EU’s green policy frameworks land at the local level. Without real engagement – without informing people, listening to them, and giving them a role – progress slows, and trust fades. If we want the green transition to succeed, it must feel like something people are part of, not something done to them.’

Crisis, as shown before in 2008, can be a teacher. And the pandemic taught many lessons: about flexibility, community, the value of every human voice. New strategies emerged. New tactics were tested. But the heart of the mission stayed constant: to unite around a shared vision, to learn, to persevere, to change destructive projects into ones of sustainability and justice.

That, in itself, is a victory.

And yet, there’s still so much work to do – across international finance, development policy, and environmental governance. But the goal remains both humble and profound: to ensure that the ground beneath our feet remains liveable. Nothing more, nothing less.

Real change doesn’t come all at once – it builds, step by step, on courage, connection, and the refusal to give up. It’s this dogged determination that fuels Bankwatch’s work. It’s what keeps hope alive. And that’s the mission we carry forward: to fight for a future where people and the planet both can thrive.