From solar roofs to shared power: Pioneering community energy in the Czech Republic

27 August 2025

Story by Klára Votavová, Jana Pospíšilová Maussen, Alexandra Lebriez, Centre for Transport and Energy, Czech Republic

A year has passed since households and organisations in the Czech Republic gained the ability to share and receive electricity. In a highly centralised energy market, developing alternative, non-profit, or community-based energy systems is far from straightforward. Legal and economic uncertainties, a limited subsidy framework, and the reluctance of energy distributors and electricity suppliers make the process even more challenging. Community energy pioneers are discovering that it will take significant effort before electricity can be shared seamlessly. Yet despite these obstacles, their early initiatives show just how much meaningful progress can be made.

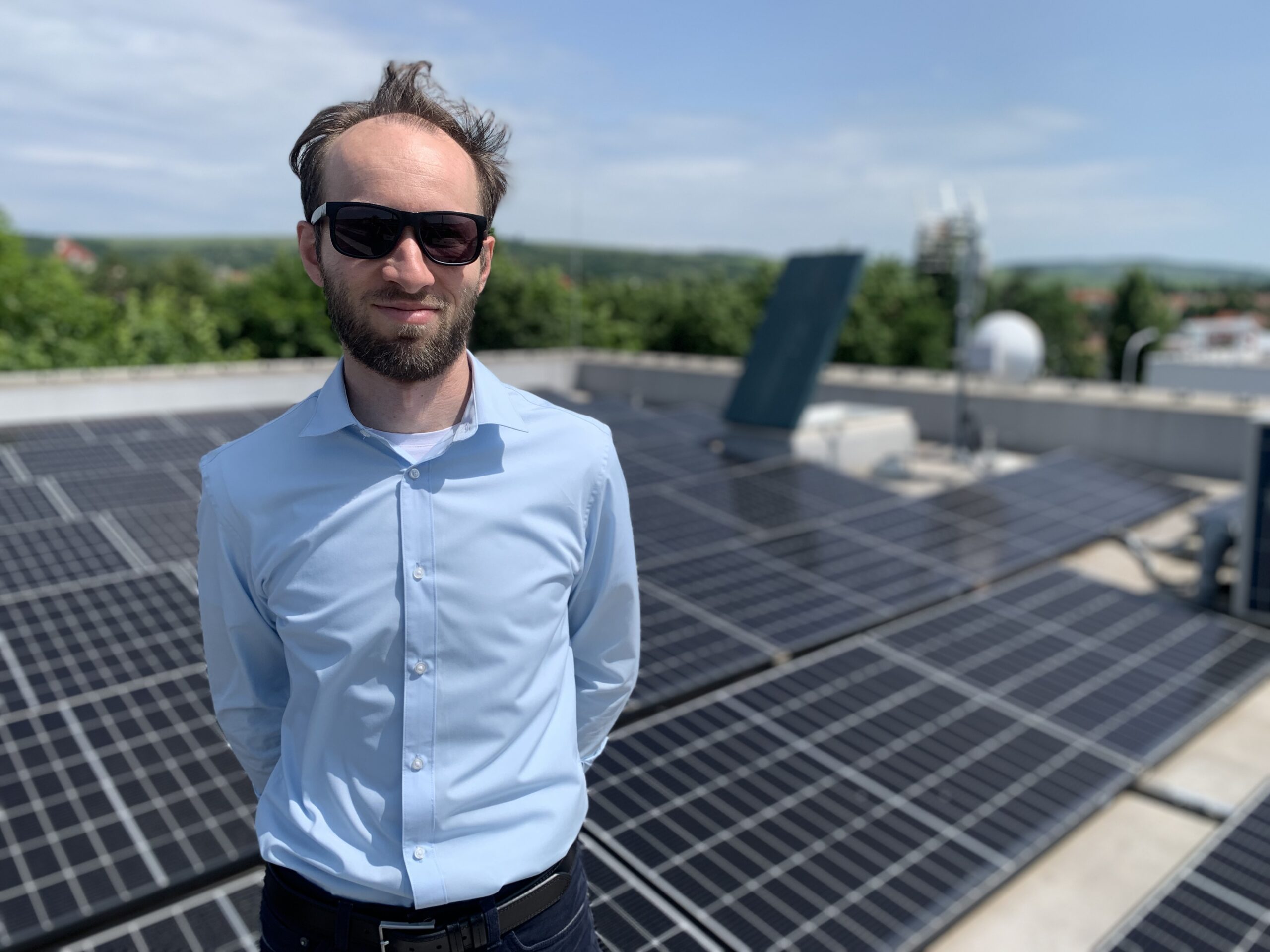

In Slavkov, near Brno, an ambulance sits in one of South Moravia’s emergency services depots, charging from the grid. The energy that powers its equipment and flashing lights comes from solar panels on the depot roof. On a warm May day, like the one during our visit, the panels generate enough electricity to power both the ambulances and the facility’s daily operations. And even then, there’s still a surplus left over for other depots in the region. ‘Our community energy project began last October. Based on our calculations, sharing electricity across 12 photovoltaic roofs has saved us CZK 150 000 (around EUR 6000) so far,’ says Tomáš Jagoš of CEJIZA, the region’s public procurement agency coordinating the project.

In the coming months, up to 250 members are expected to join – from schools and retirement homes through education and leisure centres to museums, hospitals, and regional organisations. Solar energy is currently generated across 12 roofs from 24 bases in the region, with 18 buildings participating in the energy-sharing initiative overall.

Petr Halamíček, a technician at the Slavkov depot, shows us a switchboard in the technical room. ‘From here, we feed our electricity into the grid.’ Since energy communities can’t build their own wiring networks, they rely on the regular distribution grid. Mandatory electricity meters allow community producers to record how much electricity they’ve sent to the grid and how much they’ve received.

In July 2024, an amendment to the Czech Energy Act came into force, establishing the legal framework for community energy and electricity sharing. A few weeks later, the launch of the Energy Data Centre, a national electricity-sharing data hub, paved the way for households, businesses, municipalities, and associations to produce energy – mainly from renewable energy sources – and share it across the grid. Within just six months of its launch, nearly 23,000 participants had joined the initiative.

Community energy is more than just climate-friendly – it helps to decentralise and democratise energy systems, reduce energy poverty, and increase the resilience of communities to global price shocks, such as those caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Yet its deployment has only just begun, and pioneers face a whole host of legal, economic and political obstacles.

An uncertain investment

Elsewhere in South Moravia, Jasan, a South Moravian social enterprise, recently joined the national energy-sharing initiative through an energy cooperative founded by Hnutí DUHA, a leading Czech environmental movement and member of Friends of the Earth. Asked why they took part, Renata Jandova, a representative of the enterprise, explains: ‘Our main goal is to reduce electricity costs.’

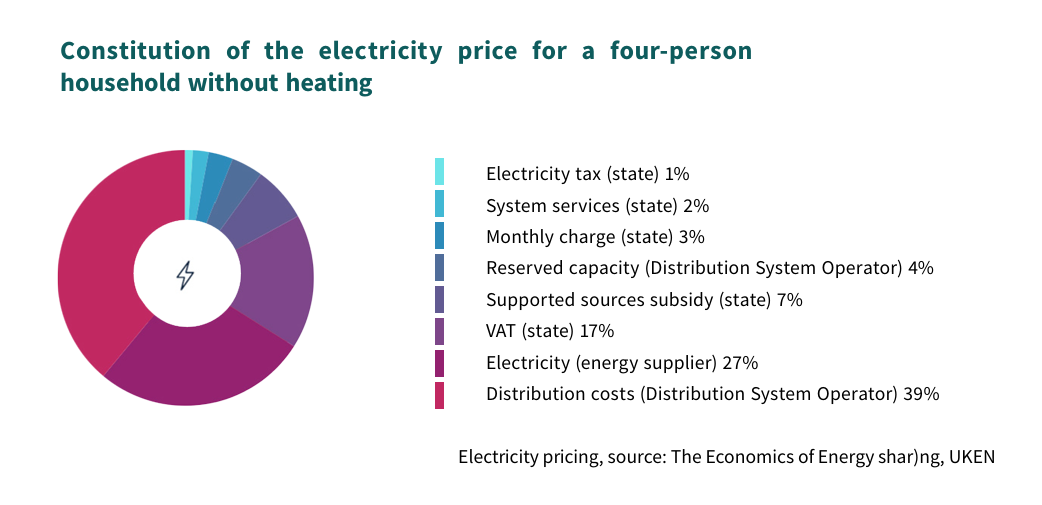

But setting up energy sharing in a profitable way is no easy feat. Returns are limited, as shared energy can only supplement – not replace – traditional energy suppliers. Members of the cooperative reduce their bills only for the portion of electricity covered by shared production. They still have to pay the distribution fees and other charges that make up most of the final bill. To make matters worse, these costs continue to increase.

Profitability is further affected by necessary upfront investments, such as the reconstruction of fuse boxes to fit the legally required electricity meters. ‘Even a CZK 30 000 (EUR 1200) investment can be discouraging for households hoping to save thousands of crowns a year through energy sharing,’ Jagoš notes. Old substations can make energy sharing expensive, even for local authorities and larger organisations managing multiple switchboards.

Jagoš highlights the challenges posed by a changing legal framework, which complicates the design of long-term, competitive business models: ‘You could say that, by sharing at this price, you’d pay off the costs within that time frame. But then a legal change might occur, affecting what was originally intended as a multi-year investment.’

Adding to the uncertainty, the Energy Data Centre, which collects data on energy sharing in the country, is currently only operating on an interim basis. This restricts both how electricity can be shared among community members and the regions in which it can be distributed. According to the Energy Law, this interim regime is expected to remain in place until July 2026. However, there are concerns the timeline could be extended, potentially disrupting the cooperative’s plans. The Ministry of the Environment has stated that the timetable is established by law and that the institutions involved are working to implement it on schedule.

When the countryside profits, so do the people

Martin Hutař, founder of the ecological farm Probio, is a trailblazer of Czech ecological agriculture. In 2008, he launched his project in the Eastern Sudetes, purchasing the facilities of an old cooperative and its surrounding fields, in the village of Velké Hostěrádky in South Moravia. There, he began cultivating wheat and raising cattle on 400 hectares of land.

Hutař runs through all the projects and groups the farm hosts: ‘We repaired what we needed, but there was a lot of unused space left over. Over time, more and more people started getting involved. Jasan started out here, and we lent them some land where they now grow vegetables. One lady started a forest tree nursery. A farming school was even established.’

The farm and its related enterprises all boast relatively low energy consumption, which is why it made little economic sense to build their own renewable energy system. Only now are its members planning to install solar panels on the roof of one of the buildings, marking the cooperative’s first photovoltaic installation.

Hutař’s approach to community energy reflects his philosophy on ecological agriculture. To him, both are ways of reviving the Czech countryside. He notes that, unlike in cities, constructing photovoltaic installations, hydropower plants, or wind turbines is much cheaper in rural areas, creating opportunities for local benefit. ‘When the countryside profits, so do the people,’ he says. ‘They’ll live and work here. But it’s crucial that we work with municipalities and create the right conditions for them.’

Cooperative or manufacturing firm?

As the Hnutí DUHA project illustrates, building energy communities in the Czech Republic on a cooperative basis is far from straightforward. Hutař was approached by the cooperative in early 2022 – two years before the rollout of the South Moravian emergency unit’s energy-sharing project. Yet to this day, solar panels have not been installed, an no concrete plans are in place.

‘All this time, we’ve been waiting for the distributor, EG.D., to rebuild the substation so they can connect us,’ says Ondřej Pašek, coordinator of the Hnutí DUHA energy cooperative. He hopes the photovoltaic installation will be up and running by autumn 2025. But delays continue to mount, despite the distributor granting the cooperative permission to connect as far back as May 2023. ‘This is a major barrier to renewable development. In so many places, new solar plants just can’t get connected to the grid,’ Pašek notes.

The Hnutí DUHA cooperative was established in December 2023 and now boasts over 200 members nationwide. Each member has one vote, giving them a say in which projects the cooperative pursues. The Velké Hostěrádky plant is set to be the first tangible example of how cooperative energy sharing will work in practice.

However, connection delays are far from unique, and the Probio farm is not an isolated case. Energy communities face difficulties securing subsidies or identifying suitable sites for renewable installations, partly because Czech legal and subsidy frameworks are not designed for cooperative or community-based energy management. ‘Most people don’t understand what we’re about,’ Pašek explains. ‘There’s a common misconception that we’re some kind of manufacturing firm.’

Currently, Czech subsidies primarily target municipalities or individual entrepreneurs, not energy communities – and especially not cooperatives. ‘One support scheme has just been opened for communities looking to build photovoltaic plants, but it requires municipal investment in the project, which doesn’t apply to us.’

From administration to investment

Pašek highlights the uncertainty of the Czech subsidy landscape: ‘The country lacks investment support with a long-term outlook. How things will look next year, nobody knows.’

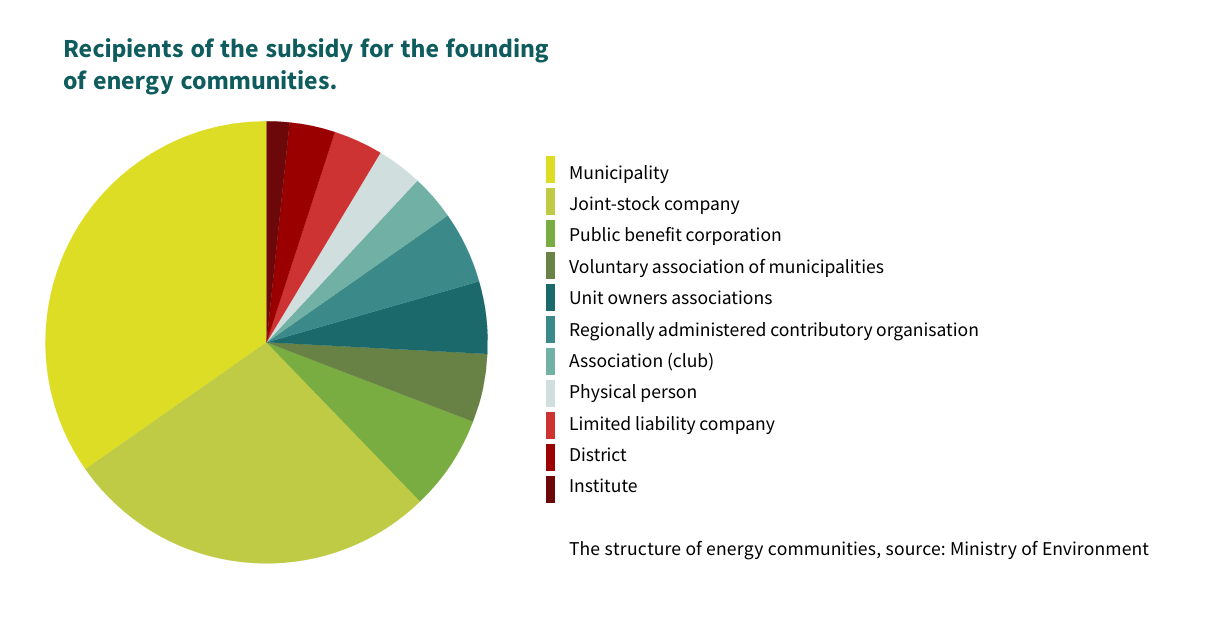

A rare example of good practice comes from a flexible support scheme implemented by the Ministry of Environment. The call included cooperatives as eligible recipients and covered administrative costs linked to the establishment of energy communities. A total of CZK 116 million (EUR 4.6 million), financed through the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility, was divided among 15 recipients, including CEJIZA, Hnutí DUHA’s cooperative, and BYTES Tábor.

Administrative setup, however, is just the start. Bigger investments – like solar panels and other renewable infrastructure – are expected to be supported by the KOMUNERG programme, a Modernisation Fund initiative planned since December 2023. In theory, about 2.8 per cent of the Modernisation Fund could be earmarked for community energy. Based on the estimated price of emissions allowances, this would amount to roughly CZK 10 to 11 billion (between EUR 400 and 440 million).

Regrettably, most Modernisation fund subsidies have thus far ended up lining the pockets of the Czech energy giants, delaying support for energy communities. The Ministry of the Environment blames the legislative process but expects the first call for projects to open in autumn 2025.

Meanwhile, community energy advocates worry that even the funds from the KOMUNERG programme may be dominated by larger players better equipped – legally and administratively – to compete for these subsidies. Another concern is that national and European priorities could shift away from energy communities and renewables towards, for example, defence spending.

If that happens, it could become nearly impossible for Czech community energy projects to remain competitive, even once the legal framework stabilises. ‘In the Czech Republic, it’s simply impossible to produce energy without subsidies,’ says Pašek. ‘Energy prices need to be guaranteed. Even the new Dukovany nuclear project tender comes with electricity price guarantees. What we wouldn’t give for that!” adds another member of the cooperative.

Community or communal energy?

Jagoš points to a peculiarity in the structure of Czech energy communities: ‘At present, we’re seeing the greatest interest coming from small municipalities. In this sense, the Czech Republic is a bit unusual. Elsewhere in Europe, it’s mostly driven by individuals at the forefront of community energy.’ Municipal involvement is also reflected in statistical data on subsidy recipients for energy communities.

Like in many other areas, the development of community energy depends on local political support – mainly that of mayors. ‘We can divide mayors into three groups. One third are innovative, forward-looking, future-oriented; they like new solutions. The lower third tends to look backward, and anything new bothers them. The last third is somewhere in the middle. It’s important to work with the innovative third and try to get the most out of the neutral third,’ says Jiří Krist, vice-chair of the National Network of Local Action Groups and president of the Opavia Local Action Group. According to Krist, interest in energy sharing is rising because municipalities see that retailers are increasingly willing to purchase their energy surpluses at lower prices.

We met Krist during a Local Action Group conference called LEADERfest in the South Bohemian town of Tábor. Daniel Urbánek, also a speaker at the conference, works as an energy technician for Tábor’s municipal energy community called BYTES. Expected to launch by the end of 2025, BYTES will involve 74 participants, mostly local firms and contributory organisations. ‘This project should have a yearly output of about 1,100 MWh. I like to compare it to one block of the Temelín nuclear plant, which produces the same amount of energy in one hour,’ Urbánek says with a humble smile.

The BYTES project initially had slightly higher ambitions, with hopes of involving households in energy sharing as well. In the end, these plans had to be scaled back due to several complications. ‘It was technically very demanding – we only had a few months because of the subsidy conditions. Had there been more time, we could have been more ambitious,’ Urbánek explains, referring to the subsidy for establishing energy communities.

This subsidy call was published in November 2023, before parliament passed the amendment to the Czech Energy Act, and all supported activities must be concluded by the end of 2025. This call illustrates the Czech subsidy framework for community energy – an uncertain and unpredictable foundation on which to build.

Due to these tight deadlines, the BYTES project shifted towards a model closer to communal energy. Krist, who coordinates ENERKOM Opavsko in the Opava region – one of the first organisations in the country to participate in community energy projects – watched this change with a critical eye. In his view, without household participation in energy sharing, community energy cannot effectively tackle energy poverty. ‘If the municipality has energy surpluses, isn’t it sensible to offer them to the most vulnerable households?’ he asks.

Decentralising a highly centralised market

Community energy pioneers are entering a market long dominated by a handful of major players – none of whom have had much incentive to support the development of decentralised, non-profit alternatives. While well-intentioned, the Energy Act amendment faced strong lobbying from energy distributors and certain energy-retailer trade unions.

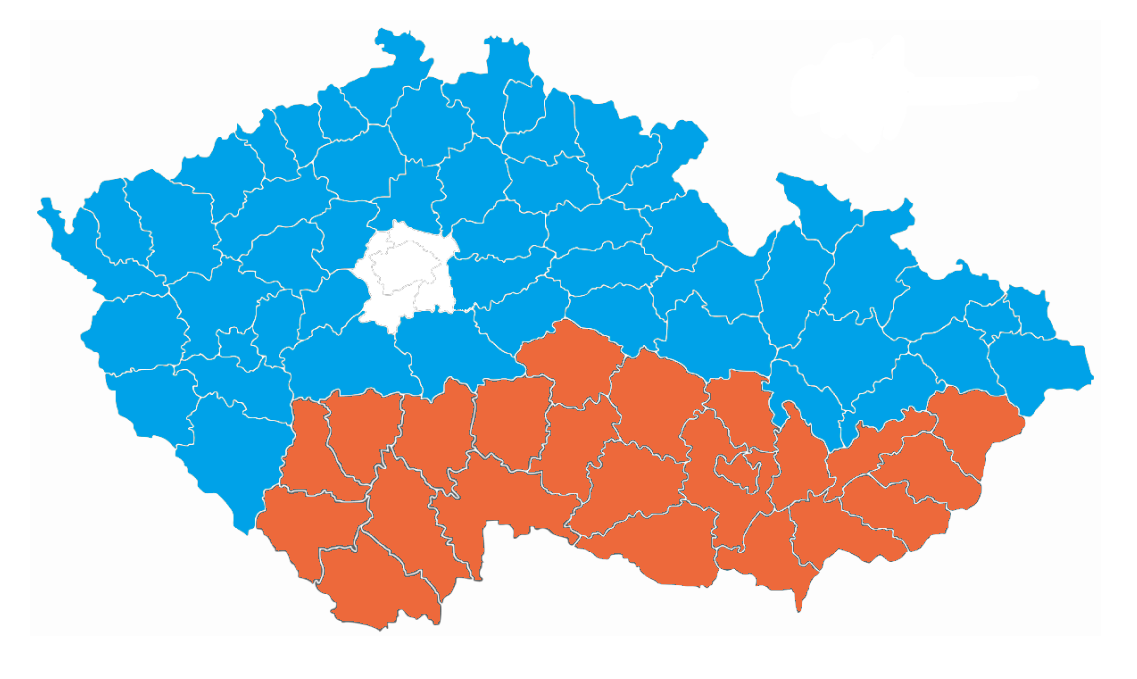

Most Czech power plants are state-owned, led by ČEZ, followed by billionaire Pavel Tykač’s Sev.en, Sokolovská uhelná, and Daniel Křetínský’s EPH. Electricity is distributed to Czech households by three distribution system operators. As shown on the map below, the majority of distribution is handled by a ČEZ subsidiary (in blue), while South Moravia and South Bohemia are administered by EG.D (in red), a private company owned by a foreign national. Prague has its own, indirectly municipally owned PRE distribution network (in white). Energy retailers – around 350 in total – then purchase this electricity and resell it to end users.

Distribution system operators are unavoidable players in the electricity market, and as shareholders in the Energy Data Centre, they should be facilitating energy sharing. Yet energy communities rarely encounter a cooperative approach. These operators often refuse to connect the renewable energy sources that communities depend on, delaying connections while citing insufficient grid capacity. While Pašek acknowledges that grid capacity is a genuine issue, he believes the operators should be better prepared to connect renewables, as their deployment is part of a long-term national strategy.

Energy communities can also face roadblocks from energy retailers. As Jagoš explains, ‘They claim we’re costing them money and that they need to reflect that in their electricity prices.’ This was the experience of CEJIZA, tasked with selecting an energy supplier for the South Moravian region. Some retailers even offered contracts that explicitly forbid energy producers from participating in energy sharing.

Better protection of energy communities against retailer discrimination was enshrined in an Energy Act amendment approved in spring 2025. For its part, the Ministry of the Environment has stated it will consider further amendments if it receives information that energy communities continue to face discrimination from retailers.

Communities take charge

The country’s first heatwave in June 2025 highlights why energy communities remain so crucial, offering a glimpse of a future Czech Republic still dependent on fossil fuels. Recent Eurostat data show that the Czech Republic is trailing the rest of the EU when it comes to renewable energy deployment. Renewable sources account for just 20 per cent of the country’s total energy production – roughly half the EU average.

Recent geopolitical events, including Israeli and American strikes on Iran and ensuing concerns over the closure of the Hormuz Strait – a route supplying one-fifth of the world’s petroleum – have highlighted the volatility of global energy markets. For Czech energy prices, the ongoing threat of liquefied gas supply interruptions remains significant. For communities, this makes local energy production and sharing not only convenient but increasingly economically sensible.

‘In the long term, this is an investment in municipal stability, self-sufficiency, and better cost control,’ says Martin Mareda, second deputy mayor of Tábor and member of the Czech Pirate Party. In June 2025, the city council endorsed the establishment of the BYTES energy community.

Jagoš believes the future will push communities to share energy more widely. Energy communities also play an educational role: ‘I see it as a driver for behavioural change. People learn a lot about how electricity works – knowledge that will be essential in the future,’ he explains. As the path becomes increasingly established, sharing should become simpler. ‘This is just the beginning. We’re the first, so it’s up to us to make it happen,’ Jagoš adds.

Energy communities can help municipalities in the Czech Republic achieve self-sufficiency. Supporting them and creating the right conditions for their development is not only a contribution to climate protection but, more importantly, an investment in a secure and resilient country – one capable of withstanding global pressures.