A new Bankwatch study, launched last week, looks at how nine central and eastern European countries are set to spend billions of EU funds until 2020 that are meant to transform the carbon-intensive, inefficient energy systems of their countries.

On our blog today, our Zagreb-based research co-ordinator comments on the findings from Croatia. Take a look at the results for other countries too and find out more at bankwatch.org/enfants-terribles >>

Croatia ought to be one of the easiest countries in Europe to transform to an energy-efficient, sustainable renewables-based economy, with its small population, relatively low energy demand, ample sun and wind resources, large areas of forest and large existing hydropower plant capacity.

The country had a favourable starting point for renewable energy compared to some other EU countries – 12.8 percent of energy in 2005 – mostly due to the fact that around half of Croatia’s 4000-plus MW of installed electricity generation capacity consists of hydropower plants built decades ago.

The problem is, however, that renewable energy development in Croatia has not got far since then compared to the potential. Successive governments have chased economically and environmentally dubious projects like the Plomin C coal power plant and the Ombla hydropower plant instead of improving the transmission infrastructure and making serious efforts to develop sustainable forms of renewable energy.

More

Climate action in EU Cohesion Policy funding for Croatia, 2014-2020 (pdf)

Study chapter | January 26, 2016

The 2009 Energy Strategy was already bizarre at the time it was adopted, and reality has only made it look worse. The Strategy predicted 3.5 percent per year growth in energy consumption. The predicted demand was to be satisfied, among other things, by 1200 MW of new coal power plants, 1200 MW of new gas-fired power plants, 1200 MW of new wind power plants and 300 MW of large hydropower.

In reality, in 2014 demand had actually decreased compared to 2010, no coal plants had been built, and only 42 MW (the highly controversial Lešće plant) of large hydropower had been built. In November 2015 it was also reported that the 230 MW Sisak C gas-fired plant had begun test operations.

New forms of renewable energy have fared somewhat better than coal and hydropower in recent years. Coal has been becoming less and less economic, while most of the hydropower potential left in Croatia is highly problematic because of its biodiversity impacts. Neither does adding more hydropower help much in terms of predictability of electricity supply considering the increasing climatic fluctuations of recent years.

Wind power, after a very slow start, has finally started to take off, with 339 MW of licensed capacity installed by November 2015. Solar photovoltaic too, has made some headway (42.9MW).

But just when Croatia was finally making progress with these plentiful resources, they hit a brick wall: The National Renewable Energy Action plan does not foresee any more solar and wind installations before 2020 because the quotas are full.

The EU is not raising this as an issue because Croatia is, even with its lacklustre efforts, on track to meet its 2020 renewable target. In 2013 it had 18 percent renewables in final energy consumption, leaving just two percent still to achieve by 2020.

EU funds to the rescue?

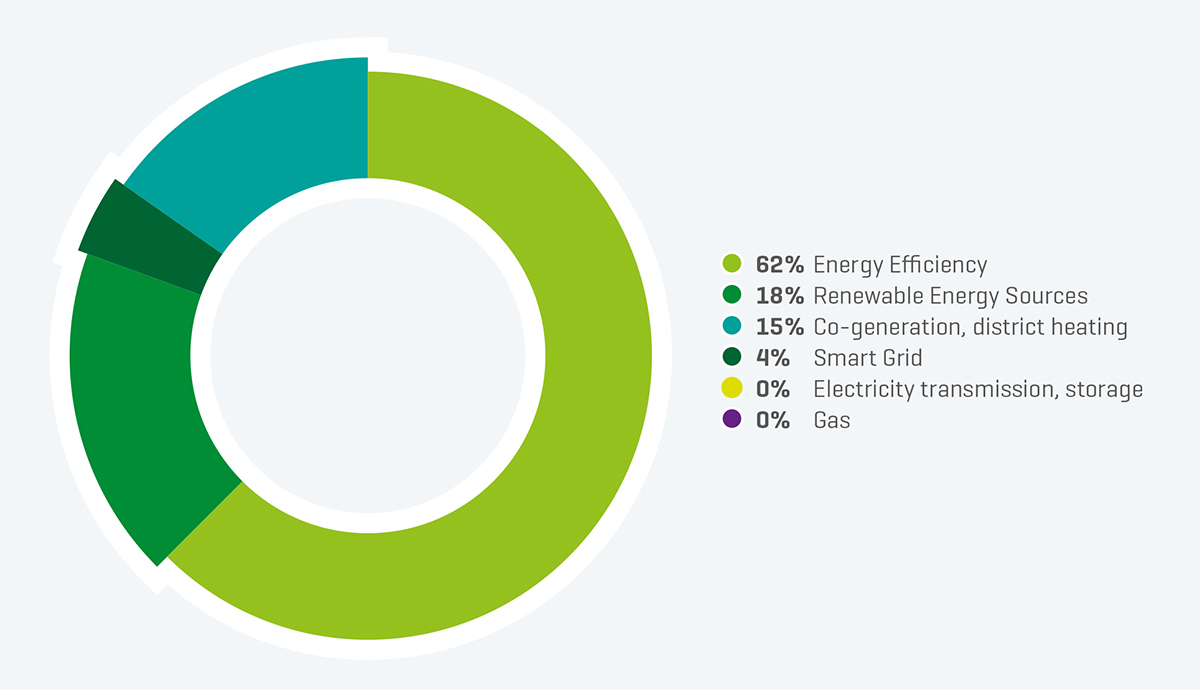

In this context it is not surprising that EU funds have a hard job supporting Croatia’s switch to clean energy systems. In the financial period 2014–2020, Croatia plans to spend around EUR 517 million on energy out of which EUR 437 million (a poor 5.16% of all Cohesion Policy funding) goes to clean energy.

The good news is that 62 percent of all energy investments are allocated for energy efficiency. However, only 18 percent, or EUR 95 million, is slated for renewable energy, and only 4 percent (EUR 20 million) for smart grids.

Graph: The different types of energy infrastructure investments in Croatia to be financed by EU funds 2014-2020

Source: Climate’s enfants terribles

This latter point is particularly worrying considering that grid stability is the main reason cited for not increasing the renewable energy quotas. Transmission and distribution ought to be one of the key priorities for matching the interest shown by the public and investors in increasing the use of renewable energy.

If there is any doubt that such interest exists, take the example of small renewable plants: Yearly quotas for small renewable plants are set at 12 MW per year and by 9 January 2014 (only 8 days from the opening of the tender) 2079 bids were submitted with a total of 87.9 MW of proposed capacities. Rather than increasing the quota, in 2015 the Croatian government decided not to contract new renewables.

So the EU funds allocations are likely to go beyond current national ambitions and make a contribution, yet they could do much more if they were based on a coherent strategy. Towards the end of 2015 the outgoing Croatian government presented a Green Paper for a Low-Carbon Strategy towards 2050, and it is to be hoped that the new government will continue this work. There are some recent encouraging signs, but ultimately decarbonisation needs a pro-active strategy, not just an absence of carbon-intensive projects. Considering Croatia’s high debts and poor economic situation, EU funds will be essential for supporting this process.

Find out more

Other chapters, graphs & more at https://bankwatch.org/enfants-terribles >>

Never miss an update

We expose the risks of international public finance and bring critical updates from the ground – straight to your inbox.

Institution: EU Funds

Theme: Energy & climate | Transport | Resource efficiency

Location: Croatia

Tags: Cohesion Policy | renewables