Transition triumphs and traps – Assessing Poland’s recent economic journey, and where it goes next

Bankwatch Mail | 4 June 2014

During last month’s EBRD annual meeting in Warsaw, Bankwatch Mail convened a discussion about the state of the Polish economy between a financial journalist and a sociologist – both residents of the Polish capital – to hear their views on some of the pressing economic issues of the day, as well as the ongoing Polish ‘transition’ process. With the 25th anniversary of the end of communist rule in Poland a few months away now (today in fact marks a quarter of a century since the first Polish elections under communism), what have been the achievements and the lessons to be learned from the last two and half decades?

About the participants

Aleksander Nowacki, who has reported for the Financial Times among other publications during his career, was born in Warsaw, and experienced higher education in the UK in the 1990s and 2000s.

Gavin Rae, a native of Birmingham in the English Midlands, moved to Warsaw in 1996 and currently teaches at the city’s Kozminski University.

This article was added on June 4 to Issue 59 of our quarterly newsletter Bankwatch Mail

Browse all articles on the right

(This article is not included in the pdf version of Bankwatch Mail 59.)

Some interesting cross-cultural and ideologically various perspectives were due to bounce around during the discussion, and we kicked off with a look at the so-called ‘Polish economic miracle’ that has seen the country enjoy the fastest rates of growth in Europe over the last two decades (over four percent a year), become the sixth largest economy in the EU, and resulted in living standards more than doubling between 1989 and 2012.

Just how miraculous has this economic miracle been?

Aleksander Nowacki: I hesitate to bring up personal anecdotes, but I remember being sent as a child to buy bread. My mother said to me that in the morning it cost 2,000, so she was giving me 4,000 at 3pm to be on the safe side. I ended up coming home without bread, as the price had more than doubled since the morning. When we talk about living standards, it’s not good just to talk about income per head. We also need to look at the fact that while the Polish economy in 1989 was maybe not as bad as Germany in the early 1920s, it was in terrible shape: there was hyper-inflation and the economy was collapsing.

And the fact that Poland is now one of the most developed countries in the world is, in some ways, miraculous, though there was nothing really miraculous about it – just hard work, and some luck, such as joining the EU.

Gavin Rae: I’ve lived in Warsaw pretty much permanently since 1996, and I’ve seen considerable changes in that time. I think the term ‘miracle’ involves an element of hyperbole, but it can be looked at as a positive example only really within the context of the post-socialist transition. In general, I would say that the post-socialist transition in eastern Europe has been a complete disaster. That isn’t supposed to be a justification of what existed before, but when you look at many of the ex-Soviet states, the declining GDP and living standards have been of an unprecedented scale in peacetime history.

When you look at Poland within this, of course, there has obviously been a much better experience, where GDP has risen significantly, living standards have risen, and so on. However, even within this, when you look at the very large deactivation of labour, the decline in many public services, particularly in health and pensions, and rising inequality, then I think that the Polish transition has not been the unprecedented success that the present government would like to portray it as.

AN: I would disagree quite strongly with some of these points. Regarding what Gavin describes as declining standards in public services such as health, between 1989 and 2010, average life expectancy grew in Poland by seven years – that’s much higher than the global average. The number of infections in hospitals was cut, I think, to 20 percent of what it had been in the eighties. The quality of health care is a lot higher than it was in the eighties: you don’t now get patients lying in beds in corridors, as was very common in the 1980s. We’ve also seen very significant advances in, for example, the treatment of and facilities for disabled people.

As for inequality, while economic inequality has indeed increased, in the eighties what we had in Poland and elsewhere in the region was ‘hidden’ inequality. In a socialist economy, how much money you had didn’t influence your position in society, or even your economic position. It was all about your contacts. So people who had contacts in the party, contacts in certain companies, could access goods that money couldn’t really purchase. So actually we had incredible inequality not in terms of income disparity but in availability of goods, and that was hidden. The inequality we have now is more transparent.

GR: To come back on health, I can agree that the system in Poland in the 1980s was particularly bad. But look at some of the figures: there are fewer doctors now in Poland than there were 20 years ago, there are fewer dentists, fewer nurses, fewer public hospitals. And we can see the health system now increasingly failing. That is of course not to say that things were great 25 years ago, and now they’re bad.

I want to go back to the statistics that you want to flag, Alex. Namely that Polish public spending as a percentage of GDP has declined quite significantly between 1993 and 2014 – from 56 percent to 43 percent.

AN: Yes, it has declined, but it has remained comparable to western European countries. What we haven’t seen in Poland, I think it’s pretty clear that these theories like ‘the shock doctrine’, that the fall of communism precipitated some kind of spiral into extreme liberalism and small government – that simply hasn’t happened. Poland has never had a ‘small’ government. It has had an inefficient government. Public spending of 43 percent of GDP is not significantly lower than that of western European countries that are, essentially, social-democratic states.

Expanding on that, how might you explain the improvements in your eyes of, for example, the health service?

“Poland has had ‘periods’ of neoliberal reform. But actually the public sector and size of the state in comparison to many other countries has remained strong. And I think this is one of the major reasons that explains why the Polish economy has fared reasonably well over the last 25 years.”

AN: The quality has improved, there is no doubt about it. Gavin has mentioned there are fewer public hospitals, but at least you see patients being treated better. I remember years ago very long queues in clinics and so on.

GR: Do you use the public health service? The queues seem now to be getting worse and worse.

AN: That may be true if you compare over the last few years, but if you compare over a longer period, that’s definitely not the case.

GR: On the issue of public spending generally, I agree with what Alex has said here in many ways. Poland hasn’t actually gone into a complete spiral of neoliberal reform – it has, though, had periods of neoliberal reform. But actually the public sector and size of the state in comparison to many other countries has remained strong. And I think this is one of the major reasons that explains why the Polish economy has fared reasonably well over the last 25 years.

We’ve touched on the equality-inequality issue. You’ll have seen the recent Polish-EU video clip, depicting Poland’s entry into the EU ten years ago and the transformation that has taken place – and produced, reputedly, at a cost of seven million zloty. Not long after watching that I noticed some recent figures that were put out in April this year by the Polish Central Statistical Office: 1 in 3 Polish children are now born into poverty. In the wider EU context, those kind of figures are some of the highest in the EU, with only Bulgaria and Romania reporting worse conditions in this particular area. What are your views on this?

AN: Poverty is a relative concept, and of course it’s a problem when children are born into poverty, no doubt about that. I would say one of the major reasons for inequality in Poland, or at least for me one of the most worrying forms of inequality is geographical inequality. I was lucky to have been born in Warsaw. If I’d been born in eastern regions of Poland, my life would have been a lot worse.

People in certain regions of Poland have very few opportunities. The statistic raised by Gavin about low labour force participation, and high unemployment, that’s partly a result of lack of opportunity in many regions, and that’s something I find very disturbing.

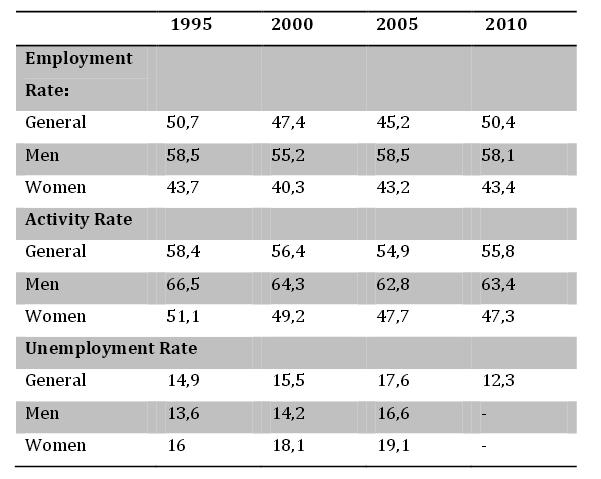

Polish employment, activity and unemployment rates by gender, from Rae, ‘The debt crisis in Poland and its impact on society’ (Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, 2014)

What do you see being done to tackle this, and do you have any proposals yourself for tackling this?

AN: From personal experience of at least one such affected area, the biggest improvements have come from Poles emigrating to the UK, Ireland and other countries for work. A lot of that emigration has been from these poorest regions, and that has probably done more to raise living standards in these regions than any government ever has.

That’s obviously a solution of sorts, but is there anything to be done at the political level?

AN: There is currently in Poland some debate about a minimum wage, and that would seem counter-intuitive in a country with 14 percent unemployment. But I think it might be reasonable to raise the minimum wage in Warsaw. However, in some parts of Poland wage levels are far too high, and may in fact be killing jobs in these areas. Also, while Poland has decentralised – one of the successes since communism, with much less centralisation – we could be doing with more sensitivity to regional issues in economic policy, and greater awareness of different needs across the regions.

GR: Going back to the EU tenth anniversary video clip, first of all – it was a very interesting thing, a bit like a propaganda film from the era of the hardline Gierek government. The portrayal is that everything is great, everything is moving forward, everybody’s happy. And, of course, part of what they show of the change in aspects of economic and social life is absolutely true.

Yet there was a 2012 opinion poll from CBOS, the Polish public opinion research people, about attitudes towards the transition and communism. Surveying people who were at least 17 years old in 1980, 59 percent said they had neither benefited or lost from the transition. Only 19 percent responded that they had benefited from the transition. The same amount said that they had lost out. So I think there’s a problem here.

I think the Polish elite and intelligentsia have got this idea, they don’t understand when they look at their lives why other people don’t feel the same way. While people may be able now to go out and shop without queues, people are struggling in different areas of life – struggling in terms of being able to find work, for instance. You listen to someone like Adam Michnik (the editor of leading Polish newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza) saying – as he does quite often – and struggling to comprehend that, when he’s abroad, everyone inquires as to how it’s possible for Poland to be doing so well, yet when he returns home everyone’s complaining. There is this clear comprehension gap. Moreover, we’ve seen two million people leave the country. I agree, in many ways this has brought benefits, but it is not a sustainable mode of development.

“It’s an economic, moral and human failure of Poland that we’ve had such a signficant out migration in search of work and we still have 14 percent registered unemployment, and I think the lowest labour force participation rate in the OECD. That is a clear failure of the Polish economic transition.”

AN: I think you are right to raise this issue. It’s an economic, moral and human failure of Poland that we’ve had such a signficant out migration in search of work and we still have 14 percent registered unemployment, and I think the lowest labour force participation rate in the OECD. That is a clear failure of the Polish economic transition. And it partly too explains why the state remains, so to speak, a big spender – yet much of this money has not gone to creating opportunities but to just merely providing people with a lifeline.

GR: I agree with that. In spite of the many successes of transition, the main failure all comes back to too many people not working. In the table I’ve provided [above], it comes down to the fact that 50 percent of society is inactive, and this is completely unsustainable on many levels, socially and economically. And this is what needs to be urgently addressed, although people have different opinions on how to do that.

Sticking to the topic of minimum wage, a major topic of debate currently in Poland, I’ll just read an excerpt from a recent Foreign Affairs article on Poland: “The greatest long-term risk to Poland is that its consumption and wages will rise too fast, crowding out domestic investment and deterring foreign business. In managing their country’s rise, Polish politicians must walk a fine line between satisfying voters’ concerns and maintaining the country’s cheap labour costs.”

Is this an ongoing conundrum that is going to be difficult to solve, especially when you throw in Poland’s regional disparities as well?

GR: I think this is an ongoing conundrum everywhere. We live in a global capitalist system. Many parts of the world’s economy are maintained through low wages, and in terms of low wages it may even get worse. This is not a problem that is unique to Poland.

If they are, however, worried about wages rising too fast, for the last two or three years real wages have been declining, ie wages connected to inflation.

AN: I’ve read that they rose 3.2 percent last year.

GR: Perhaps we have different figures on this. I may be wrong.

AN: This is interesting as I recall writing a story on this. I did an interview with a member of the Polish monetary policy council and he gave me some official figures on this that showed a real wages rise in line with productivity. Last year this was 3.2 percent, the year before around three percent as well. Let’s maybe go back and check our figures.

GR: I looked at this before we spoke, and the figure I’ve seen is that the real wages of households had reduced by five percent over the last two years. This is ‘households’, so perhaps a different way of looking at the issue of real wages.

“Poland has the highest amount of workers in the EU on the so-called ‘junk contracts’ – non-fixed, temporary contracts. The average share of workers employed on such contracts in the EU stands at less than 15 percent, in Poland it’s more than 27 percent. This has increased by more than five times since the beginning of the century, with just over five percent of workers employed on these ‘junk contracts’ in 2000. Over 60 percent of Polish workers aged under 25 are employed on ‘junk contracts’.”

There is also the question of minimum wage, and other than the issue of the deactivation of labour, you also find that Poland has the highest amount of workers in the EU on so-called ‘junk contracts’ – non-fixed, temporary contracts. The average share of workers employed on such contracts in the EU stands at less than 15 percent, in Poland it’s more than 27 percent. This has increased by more than five times since the beginning of the century, with just over five percent of workers employed on these ‘junk contracts’ in 2000. Over 60 percent of Polish workers aged under 25 are employed on ‘junk contracts’. These figures are from Eurostat and show how this creation of the ‘precariat’ comes about. Young educated workers need minimum wage and guarantee of unemployment, but, as elsewhere across Europe, it’s just not happening.

Yet look at Amazon, that’s just announced that it’s going to be opening its warehouse in the west of Poland later this year. This cheap labour does obviously attract some foreign investment, but at the same time it can be said to hold back the development of a country. I would suggest that investment over time could increase more if the living standards of the population also rise.

AN: I mostly agree with Gavin here. I would though stress that living standards have risen very strongly over the last couple of decades, and there is a relatively robust domestic market in Poland. And consumption is driving growth at the moment, rather than export or investment driven growth. And strong consumption is the way forward for Poland if the economy is to do well.

Is this consumption-driven growth underwritten by rising household debt?

AN: Poland was the one country in the EU that avoided recession following the financial crisis of 2008, and I think an unsung hero in this – perhaps not the most popular guy – is Leszek Balcerowicz, the architect of the post-89 reforms. He was president of the Polish central bank in the mid-2000s, and he started imposing regulations as early as 2004 that limited growth in credit, including household credit, and I think that was one of the reasons why Poland was not so badly and directly hit by the crisis effects. Though I think there is room for some expanding of credit.

GR: This is probably a unique moment in history for me, but I would give Belcerowicz credit on this point, though with a caveat. I was reading an economist recently on this very question of why Poland avoided recession, and the point focused on this precise issue of credit and debt, and his quote was: “We came to the party late, and we didn’t have enough time to get drunk.”

So, actually, what happened up until EU entry in 2004 was that interest rates were extremely high in Poland – they were in double figures up until the mid-2000s. The reason for this is that it was monetary policy aimed at keeping down inflation throughout the transition years. Of course, at times this had some pretty tough effects on the economy, particularly in the early 2000s. But it was sensible in the sense that you don’t want a large credit bubble to grow.

However, once Poland entered the EU, interest rates began to drop, banks were offering credits, and private debt began to grow quite sharply. But it didn’t have time to grow to dangerous levels.

AN: In 2004, the central bank passed regulations R and S, administrative measures aimed at reducing credit growth. So there was a concern and awareness already then of the potential dangers, even though credit was not very high as a percentage of GDP compared to most developed countries. Coming back to the question, I think last year saw a net decline in lending, though this year it’s expected to grow quite strongly with a rebound expected in consumer borrowing.

GR: I don’t in fact believe that Poland has seen consumption-led growth in the period since the economic crisis. I think it’s been primarily investment driven, and public investment at that. Between 2005 and 2010, public investment as a share of overall investment increased from 35 to 43 percent. During the periods of the economic crisis in 2009 and 2010, public investment as a share of GDP rose so significantly as to be the highest in the entire EU. Primarily this was because the government had access to EU structural funds, and also because of the preparations for the Euro 2012 Football Championship.

Before we get into EU money and its effects, on the level of political economy and with the national election next year in mind, what do you think are the key economic issues that will form the battleground of the election, and are the electorate going to be offered policies necessary for this stage of Poland’s development?

AN: In a word – ‘No’. The current Civic Platform government says its role is to ensure that there is ‘hot water in the taps.’ And it doesn’t, essentially, see any economic problems down the line.

The government’s take is that it’s here to ‘administer’ rather than to ‘govern’ as such. The main opposition party, Law and Justice, is interested in ‘culture wars’ – the issue of the ‘martyrs of Smolensk’ (the air crash that killed President Lech Kaczyński and 96 others). Economic matters don’t appear likely to be a major consideration in the forthcoming election.

GR: I agree with most of that. I don’t think there are major differences in the economic policies of the two major parties, though there may be some differences in emphasis. Law and Justice in the run-up to the election will probably play a bit more of a ‘pro-social’ card. What Civic Platform is likely to do is to tap and use the new EU budget money for the 2014-2020 period to maintain positive economic growth until the next election. Unless there’s a serious crisis in the EU, or if Ukraine blows up causing, for instance, difficulties in the east of Poland, then I think Civic Platform has a good chance of winning another term. But I agree with the point that currently it’s a very ‘managerial’ type of government, and it will attempt to keep to the course of the last few years.

On EU funds, since 2004 Poland’s had around 67 billion euros that’s gone largely to infrastructure. The figure for the 2014-2020 period overall is around 80 billion euros. What are your thoughts on what still needs to be done in Poland, and how to best, most effectively, use this rather big pot of EU money?

GR: Poland is the only country in the EU to have enjoyed a rise in its allocations within the first ever EU budget [for 2014-2020] to have actually decreased across the bloc as a whole. This shows how Poland is treated and viewed, especially by Germany, as very strategically important. If you look right back to the early 90s when Poland’s public debt was written off by the Paris Club, the EU isn’t prepared to do this for the likes of Greece nowadays. It signifies how strategically important the country is reckoned to be within the region.

Questions that come to mind on the forthcoming EU funding period – one, will the government have the funds available (for the co-financing) to take advantage of the new money? Poland has very strict fiscal policy: you can’t go above 60 percent of GDP, and if you surpass 55 percent you have to start bringing in certain measures such as a balanced budget. And the Polish government has just reformed – I think sensibly – the pension policy, which involved the compulsory private pension policy that has now been partly nationalised, and which immediately brought public debt down by about nine percent of GDP. This has been very controversial of course, but one of the reasons it was done was to free up space for the EU funds. So this has freed up fiscal space, though there are problems remaining with local government.

Second, what about the nature of the future spending. Not all, but a big chunk of EU money has already gone to infrastructure, not all of it good – there’s been a hefty focus on road-building rather than trains, for example. For the new round, there does seem to be more of an emphasis on entrepreneurship, training and the like, which will be good – directly – for business, but it may not have the similar stimulus effect that we’ve seen with infrastructure. And also, we don’t have Euro 2012. How much the quality of spending issue is being considered remains to be seen – whether the money can have a long-term positive impact on the economy beyond just boosting growth in the short-term.

“We’ve very likely got some major problems coming with electricity generation that could be tackled with EU money. We need a lot of new capacity, plus a lot of the existing capacity has to be replaced. More than 90 percent of electricity comes from coal, with a third of this coming from lignite.”

AN: I think an infrastructure update for Poland is still required. I’m not sure whether more new roads are necessary, but repairing existing ones would certainly be welcome. We’ve very likely got some major problems coming with electricity generation that could be tackled with EU money. We need a lot of new capacity, plus a lot of the existing capacity has to be replaced. More than 90 percent of electricity comes from coal, with a third of this coming from lignite. The transport and energy sectors for me are the key areas.

GR: Part of the problem with EU funds is actually where they can go. Creating jobs and competitive industries via the use of public investment in a productive way would be ideal. But this is really excluded from the EU funds.

We’ve talked about the health service, and health infrastructure – I’m not sure the extent to which EU funds are geared for doing this. On transport, there needs to be a serious investment in the railways. For many reasons, the rail service is grinding to a halt in many regions.

AN: One of the main reasons for this, and why successive governments have resisted spending much money on the rail sector, is that PKP – the national company – is in serious need of reform. The culture within PKP is appalling, and money invested into it essentially goes down the drain. And successive governments have been unable – I don’t know why exactly – to solve this basic problem.

Innovation, more generally, should also be addressed, perhaps as a means of avoiding what could be an emerging ‘middle-income trap’ for Poland. Very little is spent on R&D currently, for instance. And it is a big challenge – how to encourage Polish companies to innovate more, and not simply rely on cheap labour.

GR: Yes, it’s also a real loss of human capital. One of the real successes of the transition has been the huge rise in university graduates. I’ve never really experienced in the UK the level of dynamism and hard work that you encounter among young Polish urbanites. But there’s a real waste of this occurring, and not just in emigration with people moving to the UK or Ireland for jobs often below their skill-set. And in this area, things have got lot worse since the mid-90s, when jobs were available for graduates, readily and actually in Poland. The prospect now of getting good, full-time work is almost impossible.

AN: It is something to bear in mind when we consider this ‘Polish economic miracle’: in 1989, around ten percent of young people went to university. Today it’s 40 percent, of which half is paid for by the state, and this gets overlooked sometimes.

GR: It’s quite straightforward to understand this phenomenon, and this sharp rise. During communism, higher education was seen as more of a pursuit of the intelligentsia in a way – it wasn’t needed so much for strict economic reasons. Whereas now a university degree is seen as necessary to compete on the labour market.

Turning finally to the role of the EBRD in Poland. The bank is no longer what you could call a major investment player in the Polish economy. But looking at the EBRD’s key strategic directions for Poland that it has in its current Polish country strategy, there are three things: i) low-carbon economy, ii) enhancing the role of the private sector in the economy and pushing ahead with greater market liberalisation, and iii) trying to create a sustainable financial sector and capital markets. What in these points sticks out for you?

AN: There are still some sectors where there is unreasonable regulation. As for capital markets, I don’t think the recent pension reform is going to be very helpful here. Private pension funds, that have been massive investors in Polish capital markets, are going to take a huge hit, and will become a lot smaller. Financiers in Warsaw are now pretty panicky about the stock market – in short, bankers are not happy.

GR: That’s right, bankers probably aren’t happy. Though you do often hear a lot in various countries that bankers are happy, and the economy isn’t. Without opening the pensions debate, I just think the system was unsustainable – shifting that kind of public money into financial markets was not possible. I thought it was both immoral and economically incoherent.

The main EBRD-relevant issue for me here is the low-carbon economy. Unfortunately at the moment we have an alliance in Europe between the Polish government and right and the Conservative party in Britain. There’s a strong coal lobby, and the Law and Justice party here in Poland are climate deniers. Moreover, the Tusk government has been completely unprepared to take this on in any way. This is unlikely to change for some time.

AN: No, it’s not going to change. Poland is coal dependent, and basically it’s going to remain so for a while. Energy security is more of a priority than climate policy at the moment.

GR: If there’s one thing that I agree with the Polish right on, it’s that the EU should be taking this on, given the expectations on Poland of making such a transformation in its energy provision. Alas, I think, the energy security issue – being exacerbated by the Ukraine crisis – is going to take the focus away from the energy clean-up imperative.

AN: Again coming back to the economic miracle – we have seen incredible improvements in air quality in Polish cities these last 20 or so years. One of the great successes of transition is that people in Poland breathe better air.

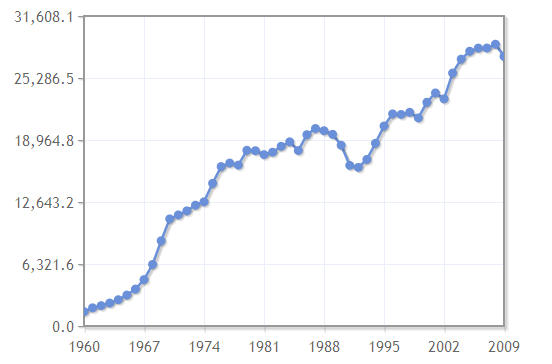

GR: I would agree with what you’re saying, but this has also come about due to deindustrialisation. Looking at the figures for Polish CO2 emissions, you can see there was quite a significant fall in emissions from the late eighties to the mid nineties, and since then it’s increased. Emissions are far higher now than they were in the nineties.

Poland’s CO2 emissions from gaseous fuel consumption (kt) (Source: indexmundi)

AN: I don’t think it’s all down to deindustrialisation. EU membership has brought in a lot of regulation in this field. I remember talking to CEOs of mining companies and power plants around 2003, and they were saying “These days they are telling us to install filters. What are these filters?” Such measures just didn’t exist up until then. These developments only came with the economic transformation.

GR: I would agree, but there’ve also been global changes. And under communism, the economic model was extensive industrial development, with no environmental consideration. EU funds of course have played a part. Just five years ago the river in Warsaw stank, but nowadays it’s a nice clean river.

AN: You can now drink tap water in Warsaw. This, for me, is a big improvement.

For the next five years of economic development in Poland, are you optimistic or pessimistic, and why?

GR: I don’t think Poland is going to be the ‘green island’ any more. I think it will be quite similar to most other EU countries, which means slow growth, and the growth will not be at a level to bring down unemployment. But there will be development, and hopefully the EU funds will be utilised in such a way as to have a long-term effect.

“The worry comes when the EU funds run out, as I don’t see there being anything to replace them, certainly not via private investment which is unlikely to be at a sufficient level to adequately step in to fill the gap.”

I think the worry comes when the EU funds run out, as I don’t see there being anything to replace them, certainly not via private investment which is unlikely to be at a sufficient level to adequately step in to fill the gap. There is of course too also the more immediate concern of how the crisis in Ukraine will pan out. Economic activity in Poland, particularly in the east but also affecting Polish exports more generally to Ukraine and Russia, could be significantly affected if the situation worsens.

AN: I would like to reiterate that the big problem Poland faces is low economic participation, as Gavin has also pointed out. I don’t really make too many predictions, but government sources I speak to tend to think that growth is going to be pretty strong over the next few years, continuing at about four percent.

Aleksander Nowacki is a financial journalist with an educational background in history. He has covered Poland, India and Africa for a variety of newspapers and newswire services, and is currently Central European Bureau Chief for the Washington DC-based Capitol Intel Group.

Gavin Rae is a sociologist at Kozminski University in Warsaw. He is author of the book ‘Poland’s Return to Capitalism – From the Socialist Bloc to the European Union’, runs the blog ‘Beyond the Transition’ and tweets @BeyondTransitio

Theme: Social & economic impacts

Location: Poland

Tags: Aleksander Nowacki | BW Mail 59 | Gavin Rae | Poland | transition

Never miss an update

We expose the risks of international public finance and bring critical updates from the ground. We believe that the billions of public money should work for people and the environment.

STAY INFORMED