Nabucco gas pipeline

The Nabucco pipeline project is based on the idea to bring Caspian or Middle Eastern gas through Turkey to the EU. Its planned route is 3300 kilometres long with an estimated construction cost of almost EUR 8 billion.

This is an archived project. The information here may be out of date.

Learn more about our current projects and sign up for the latest updates.

The planned route of the Nabucco pipeline. Source: Wikimedia Commons - http://bit.ly/2x0SnRJ

Stay informed

We closely follow international public finance and bring critical updates from the ground.

Key facts

- planned final capacity is 31 billion cubic metres of gas

- half of the estimated costs (EUR 7.9 billion) could be financed by international financial institutions

- in September 2010, the European Investment Bank (EIB), the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), and the International Financial Coorporation (IFC), the World Bank’s private lending arm, initiated their appraisal procedures

Key issues

- Source for the gas is supposed to be Turkmenistan, one of the most authoritarian countries in the world.

- Public financial and political support for fossil fuels investments undermines EU climate policy targets.

- Real energy security and independence can be achieved by increased energy efficiency.

Background

Among the main promoters of the project are the European Commission (EC) and several EU member states. The main justifications for Nabucco are its role in ensuring energy security and fighting climate change.

Yet there remain serious doubts over whether the Nabucco pipeline can help to solve any of these problems. Moreover, it will bring limited public benefits and comes with serious social and environmental concerns.

Bankwatch believes that Nabucco should not receive public support, either financial or political.

Four important reasons for not providing public funds for this project.

For many years the Nabucco project has faced problems when it comes to guaranteeing sufficient gas supplies. The only country offering enough gas is Turkmenistan, one of the most authoritarian regimes in the world (in a recent Freedom House survey, Turkmenistan received the same score as North Korea).

The imprisonment of Turkmen environmentalist Andrey Zatoka, who was subsequently released with a fine and expelled from the country, proves that the situation in the country is still critical.

As the EU recognises Nabucco as its priority project and the EIB is considering financing it, we request that these institutions take into account the serious human rights violations occurring in Turkmenistan, as exemplified by Mr. Zatoka’s case.

Mr. Zatoka is one of numerous political prisoners in Turkmenistan. Many others continue to sit in Turkmen prisons without relevant legal protection. When considering possible cooperation with Turkmenistan within the EU’s energy sector, the member states should seek to ensure that they do not undermine their own efforts to improve human rights standards and build democracy.

The absence of pluralism in Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan (another potential supplier of gas for Nabucco) makes public oversight over gas and oil revenues impossible. Furthermore, revenues generated from the extractive industries provide such governments with additional power to frustrate – if not crush – the bottom-up struggle for democracy.

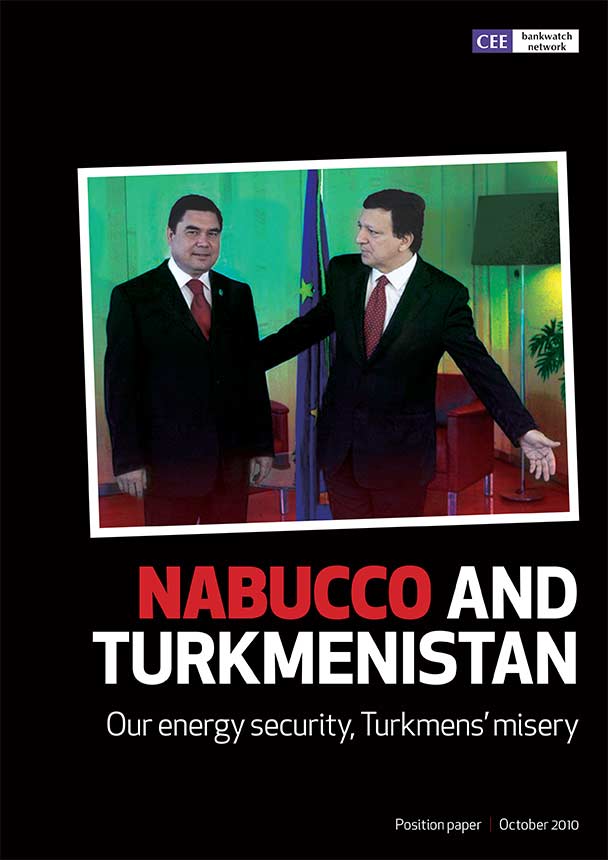

Position paper: Our energy security, Turkmens’ misery

If the political dialogue with Turkmenistan is to bring any results for changing this corrupt and undemocratic regime, a clear signal has to be given now. Negotiations over the supply of Turkmenistan’s gas to Europe should be preceded by the formulation of measurable benchmarks to show the transition of Turkmenistan towards becoming a more democratic state. These demands should be made public. Only when they are met, should the EU move to initiate business negotiations over gas supply.

Public financial and political support for fossil fuels investments undermines EU climate policy targets. If we commit to Nabucco now, Europe will be using it for importing gas in at least 50 years’ time. We believe that public financial and political support should be exclusively focused on energy efficiency and renewables.

Nabucco is often described as a means to decrease the greenhouse gas emissions of the EU. This argument is valid only in relation to the general belief that gas is not as bad as coal. If Nabucco reaches its full capacity, in the 2020s, it will import to Europe 31 billion cubic metres of natural gas per year.

This means that in the combustion process approximately 60 million tonnes of additional CO2 will be emitted in Europe per year. This is more than half of Romania’s CO2 yearly emissions in 2007 from all sectors. On top of that, methane – the principal component of natural gas – has 25 times higher greenhouse effect potential than CO2. During extraction and transportation a few percent of natural gas leaks into the atmosphere. Taken together, this evidence suggests that natural gas cannot be seen as a low-carbon alternative.

Furthermore there is no proof that gas will replace dirtier energy sources. On top of that no life-cycle analysis of gas from Nabucco has been conducted. It remains unclear how much CO2 will be emitted to generate the energy needed to pump gas the distance of more than 4000 km from Turkmenistan to Austria.

Support for large-scale gas infrastructure projects is rather inconsistent when it comes to ambitious EU climate targets and raises the question of the integrity of EU policies ahead of the extremely important climate summit in Copenhagen in December 2009.

The European Investment Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development should stop financing fossil fuels projects like Nabucco althogether. The banks’ support for fossil fuels contradicts the European Parliament’s November 2007 resolution on trade and climate change, calling for “discontinuation of public support via export credit agencies and public investment banks, for fossil fuel projects.”

Real energy security and independence can be achieved by increased energy efficiency. Central and eastern Europe wastes a lot more energy than western Europe, and this is clearly detrimental for the region’s economies. We can, though, achieve the goal of energy security by rationalising our energy use, for example: insulating houses, lowering losses in transmission of energy and heat, increasing the efficiency of existing power generation units, and better integration of EU energy market.

In contrast to the focus on supply side measures like the Nabucco pipeline, a study by the Central European University (CEU) from June 2010 details how a bigger emphasis on energy efficiency via a strong retrofit programme in buildings would benefit Hungary: For January – the peak month for imports, and the month of highest risk for energy security – the energy savings achieved by 2030 would be equivalent to 59% of Hungary gas imports reducing dependency on Russian gas.

The often raised arguments that Nabucco will guarantee stable gas supplies to Europe are contradicted by strong indications that the proposed sources of supply may not be trustworthy. The undemocratic political systems and lack of rule of law in the potential supply countries, such as Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan, make long term contracts with them unreliable. This has been seen many times in the energy cooperation of these countries and Russia. On top of that, the transportation of gas for Nabucco near conflict regions in the Southern Caucasus (in Azerbaijan and Georgia) makes the lasting stability of these supplies even more doubtful.

If the EU is serous about its energy and climate targets, the switch from the public financing of fossil fuels towards green investments needs to take place now. The various cost estimations of the investments needed across the EU range from EUR 13 billion at the low end (estimated by the European Commission) up to EUR 44 billion (estimated by the Dutch consultancy Ecofys) to be invested into energy infrastructure by 2020 on an annual basis.

Unlike big fossil fuels investments, concentration on energy efficiency will not only contribute to energy security and emission reductions, but can also reap numerous ancillary benefits (“double dividend”) for social cohesion and economic development such as reducing energy bills for households and providing new employment and business opportunities, especially in the sector of small and medium enterprises.

According to the above mentioned CEU study, a retrofit programme in those enterprise buildings may bring up to 131,000 net jobs by 2020 – with losses in the energy supply sector taken into account.

Previous experience with large-scale politically motivated fossil fuel investments such as the Chad-Cameroon pipeline (financed by the World Bank Group and the EIB – more info here) and the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline (International Finance Corporation and European Bank of Reconstruction and Development – more info here) has shown that the engagement of international financial institutions does not guarantee benefits for local people. This development model strengthens mainly multi-national oil companies and undemocratic governments.

Nabucco is receiving significant public support even though:

- It may ultimately benefit the governments of the most authoritarian regimes in the world at the expense of citizens.

- No assessment of an alternative way to deliver energy security, through increasing energy efficiency for example, has been conducted.

- It may involve Europe in long-term cooperation with unstable regimes that do not always stick to contractual commitments on gas deliveries.

- No political risk assessment for the whole project has been made public.

- No climate assessment of the project as a whole has been done.

Latest news

Rotten perceptions, grim reality Turkmenistan off the agenda in European Parliament, Nabucco still nowhere near fit for purpose

Blog entry | 26 October, 2010Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, launched today, confirms Turkmenistan’s position as one of the world’s least democratic regimes. Promoters of the Nabucco gas pipeline project have opted to adopt a surprisingly tolerant approach to Turkmenistan’s endemic failings.

Read moreNo public money for Nabucco – mega gas project a drain on clean energy, human rights and the environment, says Bankwatch

Press release | 6 September, 2010Budapest, Hungary — Reacting to today’s announcement by the Nabucco Consortium that international public banks are now officially commencing their appraisal of the EUR 7.9 billion (estimated) Nabucco gas pipeline project, watchdog group CEE Bankwatch Network called on the international financiers to reject what would be record European public finance for the project and instead to focus on the financing of clean energy in central and eastern Europe, particularly climate-friendly, job-boosting energy efficiency.

Read moreRelated publications

EBRD maintaining relations with Turkmenistan regime

Bankwatch Mail | 14 May, 2012 |Following the EBRD’s controvesial adoption in 2010 of a ‘calibrated strategic approach’ to guide its activities in the totalitarian state of Turkmenistan, annual discussions between the bank and civil society organisations have been taking place, with the most recent last month.

Energy Security For Whom? For What?

Study | 16 February, 2012 | Download PDFHow can fossil fuels and uranium be kept in the ground and agrofuels off the land in ways that do not inflict suffering upon millions? Mainstream policy responses to these issues are largely framed in terms of “energy security”. Yet far from making energy supplies more secure, such policies are triggering a cascade of new insecurities for millions of people.

Nabucco and the Arab Spring

Briefing | 15 May, 2011 | Download PDFThe democratic revolutions in North Africa and the Middle East have not quite spread it to the authoritarian regimes of Central Asia. Nevertheless nervous reactions among leaders in these countries have proven another weakness of the proposed Nabucco pipeline project, in that the stable gas supplies promised by the project under the capacious term “energy security” are much less “secure” than previously expected.