Zarafshan, Bash and Dzhankeldy wind projects, Uzbekistan

The first large wind projects in the Central Asian country are being built in biodiversity hotspots and hinder the declaration of protected areas. The IFC, EBRD and ADB need to ensure that some of the most problematic turbines are moved away.

Stay informed

We closely follow international public finance and bring critical updates from the ground.

Key facts

Project promoters:

- Zarafshan, 500 MW: Masdar – Abu Dhabi Future Energy Company PJSC

- Bash, 500 + 52 MW: ACWA Power (Saudi Arabia)

- Dzhankeldy, 500 MW: ACWA Power (Saudi Arabia)

Lead contractor:

- Zarafshan: Sepco III (China)

- Bash: China Energy Engineering Group Co Ltd

- Dzhankeldy: China Energy Engineering Group Co Ltd

Total project cost:

- Zarafshan: USD 593.4 million. Lenders include IFC, EBRD, ADB, JICA, Dutch Entrepreneurial Development Bank, Natixis, First Abu Dhabi Bank

- Bash: USD 627 million. Lenders include EBRD, ADB, etc.

- Dzhankeldy: USD 644 million. Lenders include EBRD, ADB, etc.

Key Biodiversity Areas/Important Bird Areas nearby:

- Zarafshan: Mount Aktau

- Bash: Lake Ayakaghitma and surrounding desert

- Dzhankeldy: Karakyr lakes

Proposed protected areas:

- Zarafshan: Aktau-Tamdy state reserve

- Dzhankeldy: Kuldzhuktau sanctuary

Key issues

- Multilateral development banks must encourage the Uzbek government to legally protect the Aktau-Tamdy state reserve and Kuldzhuktau sanctuary within their scientifically justified borders.

- Renewable energy projects in Uzbekistan must avoid impacting the conservation objectives and integrity of protected areas, priority biodiversity features and critical habitats.

- Wind turbines and transmission lines must be moved away from core areas of the most threatened species of birds.

- The design of the Zarafshan, Bash and Dzhankeldy wind power projects should be adjusted to ensure sufficient buffer zones.

- The 34 turbines of the Bash project closest to the Ayakaghytma lake important bird area should be moved east of the border.

- Some transmission lines should be buried underground.

- The strategic environmental and social assessment (SESA) of renewable projects in Uzbekistan should be developed in a transparent and participatory way and approved by the government.

- The SESA should address potential transboundary effects (e.g. on migratory birds). Similar assessments should be done in other countries before large renewable projects are financed.

Background

According to Uzbekistan’s Green Economy Transition Strategy 2019-2030, by 2030, Uzbekistan aims to double the share of renewable energy sources in its total electricity generation, bringing renewables up to 25 per cent. In 2019, the government signed agreements with the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) to scale up solar and wind power projects in the country.

In 2022, the government selected wind projects with a total capacity of 1,600 megawatts (MW) based solely on economic criteria, without heed to sensitive areas for biodiversity. In 2023-2024 construction started on three projects – Zarafshan, Bash and Dzhankeldy. Another 100 MW project (in Karakalpakstan autonomous region) has been approved for financing, as well as the expansion of Bash.

Gone with the wind – protected areas not declared due to wind projects

All three projects are located within or will have significant impacts on proposed protected areas and internationally recognised areas. The Zarafshan wind power project would impact an Important Bird Area, Key Biodiversity Area and a proposed state reserve. The Bash project would affect an Important Bird Area and a Key Biodiversity Area. The Dzhankeldy project is located within a proposed sanctuary.

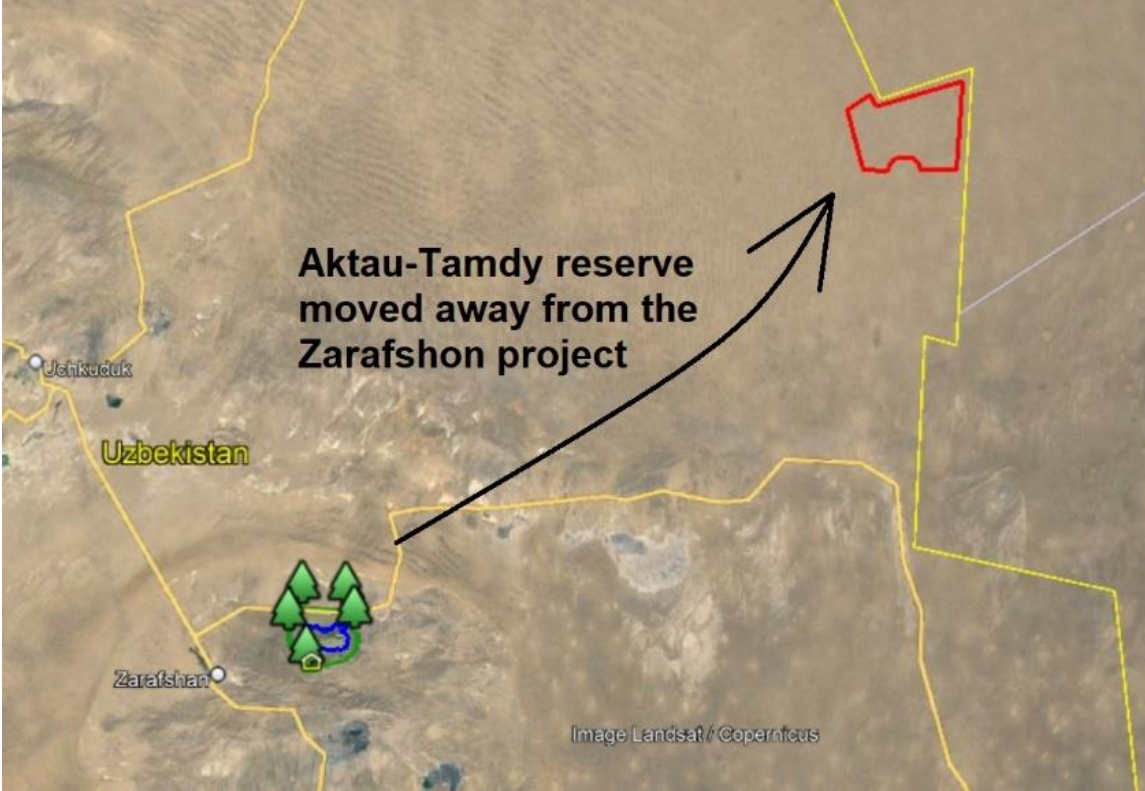

The Zarafshan wind project is probably the main reason for ‘moving’ the Aktau-Tamdy state reserve away from the scientifically proposed borders, as two of the turbines were located within the proposed area. The Tamdytau mountains surrounding the project site were proposed for protection after extensive research under several projects, including by UNDP-GEF.

The results of the UNDP-GEF project were endorsed by the Uzbek government and include a map and description from 2013, where it is clearly visible that the protected area called Aktau (Tamdy) in the Tamdy district is located around the highest peak in the Kyzylkum desert – Mount Aktau. This is the last remaining habitat of argali sheep in central Uzbekistan, contains many nests of threatened birds and is home to endemic flora. Part of the area was declared an Important Bird Area in 2007 and later a Key Biodiversity Area.

When in February 2022, a presidential decision declared a 40,000-hectare piece of pastureland in the Tamdy district to be the Aktau-Tamdy state reserve, without specification of the exact location, experts thought that Mount Aktau would be finally protected.

However, in an email to Bankwatch from 17 August 2022, the EBRD claimed that the Aktau-Tamdy state reserve would not be located within the project site, but more than 100 kilometres away. A map provided by Masdar on 8 October 2022 confirmed that the new protected area would be located in the Tamdy district, but next to the border with Kazakhstan. This is part of the Kyzylkum desert, away from the Tamdytau mountains, in a place that had never previously been proposed for protection.

Similar problems apply to the Dzhankeldy wind power project – half of the project is located on the Kuldzhuktau ridge, which was proposed as the Kuldzhuktau sanctuary (zakaznik in Russian) by the same UNDP-GEF project for paleontological, botanical and zoological reasons.

Furthermore, the Zarafshan and Bash projects are located very close to Important Bird Areas and Key Biodiversity Areas. Although the turbines are located just outside the borders of those areas, no appropriate assessment on the specific impacts on these areas was carried out.

After Bankwatch raised the alarm, Masdar, the EBRD and the IFC recognised the need to protect Mount Aktau and promised to engage with the government. Consultants hired by Masdar met with representatives from the Ministry of Ecology, but as of February 2024, according to Masdar, the government had stopped any studies or steps towards protection. This unique area next to the Zarafshan project, as well as the areas next to the other wind projects, remain unprotected and threatened by new mining and energy projects.

A bird’s eye view – impacts on threatened bird species

All these wind projects are located in core areas of globally and nationally threatened bird species, with especially significant impacts caused by turbines situated close to nests of Egyptian, cinereous and bearded vultures, Eastern imperial and golden eagles, and saker falcons.

The new transmission lines for the Bash and Dzhankeldy projects might pose a significant collision risk for the Asian houbara bustard and trigger the Banks’ critical habitat requirement. The Bash project has 34 turbines located on the edge of the Ayakagytma lake Important Bird Area, potentially threatening a variety of water birds.

In a response to Bankwatch dated 15 November 2022, the IFC acknowledged that ‘[the Zarafshon project area] is an important area for a number of raptors’ and committed to ‘implementing the mitigation hierarchy, starting with avoidance by moving 15 turbines’. However, as Masdar explained to Bankwatch during a workshop in November 2022, these turbines were moved away based on old findings, not on the most comprehensive nest survey finalised in 2022, which found new nests in areas close to proposed turbine sites.

This was the case at the other project sites as well. Detailed nest surveys were done in 2022, when the locations of the wind turbines were already fixed in the environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) reports. After the 2022 nest survey at Dzhankeldy, for example, the ESIA study was updated with several new nests found, but, according to the updates, the ‘turbines could not be microsited further away from the known nesting locations due to technical and economic constraints’. This raises questions about the relevance of the proposed avoidance and mitigation measures.

The best international practices (on-time nest search, core area delineation, satellite telemetry) were not used when assessing the impacts on nesting birds. The core area is recognised as the most vital area for population survival, and consequently, its biologically meaningful delineation is of great importance for robust conservation decision-making and spatial planning.

The wind turbines were not moved away from the core areas of the key species, but rather some minimal buffers from the active nests were proposed: 500 metres (Zarafshan), 750 metres (Bash) and 750 metres ‘where possible’ (Dzhankeldy). These were not based on field research, yet scientific articles and national standards recommend excluding the entire core zone of threatened species, identified for example by tracking the pairs for at least one year.

Probably the most underestimated impact within the ESIA studies is on the globally endangered saker falcon. Hungarian studies show that adult sakers avoid wind turbines, meaning that those areas between the wind turbines are lost habitats for them, even if there is plenty of food there. Juvenile sakers are less afraid of wind turbines, which makes them more at risk of collision. Recent data shows that two such falcons were killed in Austria after colliding with wind turbines.

One important improvement is that a shutdown on demand system called IdentiFlight will be installed to halt the operation of specific turbines if priority bird species fly close by. However, this system has significant limitations and cannot solve the problems of wrongly placed turbines.

In meetings with Bankwatch, all lenders committed to reviewing the 2022 results of the raptor surveys, but were reluctant to consider changing the location of wind turbines based on potential impacts to bird nests. Moreover, the 2022 studies were made available to Bankwatch (with erased exact nest locations) only in December 2023 when the construction of the Zarafshan project had started.

Better late than never – strategic environment and social assessment (SESA) can help avoid future problems

Up until now, the government has allocated plots of land to projects with no consideration of the environmental risks or impacts. As such, IFC, EBRD, ADB and other lenders have almost no way to avoid the impacts caused by poor placement, apart from not investing in said projects, which should also be an option when the risks are high. Therefore, policy dialogue between the lenders and the Uzbek government is critical for making sure that project siting takes environmental considerations into account.

There is no adopted legislation for strategic environmental assessment (SEA) in Uzbekistan,

only a draft law, and there is a lack of overall awareness of SEAs and capacity to coordinate them among government authorities.

In 2023, the EBRD initiated the development of an SEA of renewable projects in Uzbekistan, which also includes a social assessment – strategic environment and social assessment (SESA). Results from the AVISTEP sensitivity tool developed by BirdLife International would feed into the SESA, which should be ready by early 2025.

Although the assessment will not be legally binding, it should help the government choose better locations for renewable projects and avoid biodiversity-sensitive areas. This is an important step in ensuring an environmentally responsible transition to clean energy, but doesn’t solve the problems of the wrongly placed Zarafshan, Bash and Dzhankeldy projects. Some other greenfield projects under appraisal, such as Kungrad 1, 2, 3 on the border of the South Ustyurt National Park and UNESCO World Heritage Site might also go forward before the SESA is ready. The international lenders must do their utmost not to let this happen.

Additional information:

- Briefing: A False Start for Wind Energy in Uzbekistan?, CEE Bankwatch Network, December 2022.

- Update: Wind Energy Projects in Uzbekistan, CEE Bankwatch Network, May 2023.

Latest news

Related publications

Dispute resolution agreement on Zarafshan wind project

Official document | 3 December, 2025 | Download PDFA dispute resolution agreement was signed by CEE Bankwatch Network and Shamol Zarafshan Energy Foreign Enterprise LLC in October 2025. The agreement is the result of a year-and-a-half-long dispute resolution process supported by the Compliance Advisory

A false start for wind energy in Uzbekistan?

Briefing | 1 December, 2022 | Download PDFThis report analyses the current environmental assessments for four wind projects planned to be built in Uzbekistan and adds new evidence from visits to the sites, meetings with the companies and local communities, and expert advise from environmental organisations.