A 3-page draft law initiated by former energy minister, Sebastian Burduja, last week sent shockwaves among coal dependent communities and climate activists alike. Accompanied by 50 pages of justification, wrapped in national security rhetoric and delivered with a side dish of geopolitical fear tactics, the draft law aims to derogate from the country’s Decarbonisation Law. It re-opens the possibility of building new coal power plants and operating new and existing ones alike, under vaguely formulated conditions.

But strip away the alarmist language about Russian invasions and infrastructure attacks, and what remains is a cynical attempt to derail Romania’s energy transition, betray coal-dependent communities, and potentially defraud the EU of EUR 2.14 billion – Romania’s allocation under the Just Transition Fund.

Manufacturing crisis for political gain

The 50-page justification opens with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the shock it delivered to EU energy markets. However, it omits to acknowledge that since then European energy markets have recovered and diversified. The EU’s response wasn’t to resurrect coal, it was to accelerate renewables.

Romania itself has surpassed its renewable energy targets, adding more than 1,200 megawatts in 2025 and projecting between 2,500 to 3,800 megawatts this year. The energy landscape is transforming rapidly, but you wouldn’t know it from reading this law’s apocalyptic preamble.

The justification then goes on, suggesting Russia might attack Romania’s electricity infrastructure, therefore reserve coal capacity is needed. This isn’t energy policy, it’s fear-mongering dressed up as strategy.

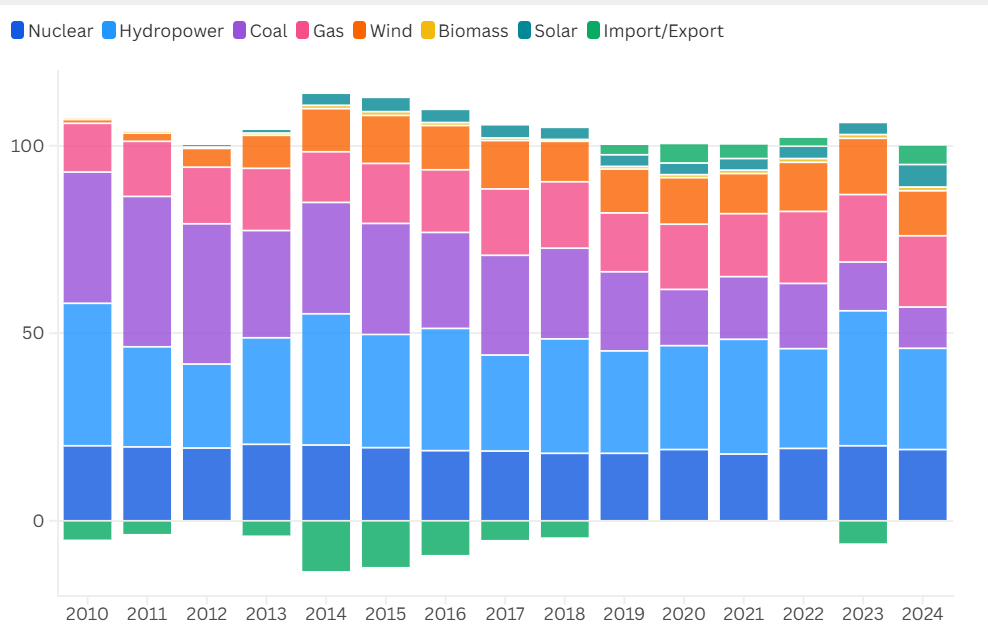

Arguably, one of the most disturbing details is the law’s citation of a national security strategy from 2010, which indeed mentioned coal stockpiles for security reasons. In 2010, coal contributed roughly 20-25% to Romania’s energy mix. Now it is just 13.7% and keeps falling. Context matters.

In 2025 it was renewables that supplied the largest share of Romania’s electricity mix: wind, solar and hydropower. Interconnection capacity with neighbouring countries has expanded, storage is catching up. The grid looks fundamentally different. Using 2010 data to justify 2026 energy policy is not only outdated, it’s deliberately cherry-picking a moment in time that supports a predetermined conclusion, while ignoring 15 years of transformation.

The Just Transition Fund – taking the money but refusing the transition

In 2022, Romania received an allocation of EUR 2.14 billion from the EU Just Transition Fund (JTF) specifically to support coal phase-out by 2032. This fund is designed to support almost 30,000 workers through retraining and to create approximately 11,000 new jobs. The whole logic behind the JTF funding is Romania’s commitment to transition away from coal. Without coal phase-out, there is no transition to fund. And who will be deceived at the end of this political theatre yet again? Coal-dependent communities, who are regularly given false hopes by politicians that lack courage to plan for the real future.

The State aid paradox

Oltenia Energy Complex, Romania’s main lignite producer, has since 2021 received hundreds of millions of euros in State aid specifically for closure operations. The country’s hard coal mine operator was also granted nearly EUR 800 million State aid for closure in 2024. This money has already been disbursed and spent, justified under EU State aid rules as compensation for the costs of phasing out uneconomic coal operations.

State aid for closures is legal under EU rules precisely because it facilitates an orderly phase out of operations that would otherwise fail in the market. Closure is the key condition for the aid.

Now, Burduja and thirty other parliamentarians want to put coal ‘back on the table and into production’. But what happens to the hundreds of millions in closure aid already received? If coal operations are to continue, that State aid becomes illegal retroactively. It was granted under false pretences. Under EU State aid rules, illegal aid must be recovered, with interest. This additional financial burden could very well destroy the industry they are trying to revive. And the law should explicitly stipulate the mechanism for returning this aid to the state budget. It doesn’t.

So this adds another bill to the tab: EUR 2.14 billion in Just Transition Funds received under commitments this law would violate, and over EUR 3 billion for restructuring of Oltenia Energy Complex and closure of hard coal mines. This is over EUR 5 billion that is likely to be lost if this law is adopted.

The communities politicians claim to protect

Every year that politicians delay the inevitable coal phase-out is another year of distraction from genuine alternatives. Every legislative attempt to extend coal operations signals to potential investors that Romania isn’t serious about transition.

The cruel irony is that this law, which will be used in political discourse as protecting coal workers, ensures their continued precarity and prolongs a structural limbo. For some, this has been going on for over a decade. It perpetuates dependence instead of facilitating transition. It offers the illusion of security while postponing the hard work of creating actual alternatives.

Ruling by fear

This coal revival law didn’t arrive in isolation. It was submitted to parliament on the same day as another Burduja initiative: a law to classify hydropower plants as military objectives of national security. Both laws invoke ‘national security’ to bypass environmental procedures in force, protected areas regimes and property law. Both weaponize fear of war, enemies, and sabotage. ‘National security’ has become a new catchphrase that short-circuits democratic deliberation, environmental protection, and transparency.

What about ‘We need coal for grid stability’?

Romania’s grid is already diversifying rapidly, renewable capacity is expanding by thousands of megawatts annually and interconnection with neighbouring countries has improved significantly. Grid stability doesn’t come from clinging to 20th-century baseload thinking, but from diversification, storage solutions, smart grid technology, and interconnections that allow for flexibility and resilience.

The choice ahead

The choice to phase out coal was made years ago, and is justified by economics, climate imperatives, and EU commitments that make this trajectory inevitable. The real question is whether this will happen in an orderly, just manner that supports affected workers and communities or whether politicians will delay until crisis forces chaotic closures without support systems in place.

This draft law offers the illusion of security while guaranteeing instability. It invokes the protection of workers while blocking their access to transition support. It wraps itself in national security rhetoric while undermining Romania’s actual long-term energy security. Finally, it is financially reckless, facing the prospect of having to give back billions of euros in closure aid. If Romania is to stay on the path of prosperity and sustainable development, this law must be rejected.