The Nenskra dam is the largest of Georgia’s massive plans for hydropower installations in the Upper Svaneti region. If realized, it will deprive the local indigenous communities of their ancestral lands and traditional livelihoods, and cause an irreversible damage to the fragile river and mountain ecosystems.

Never miss an update

Receive our monthly overviews of the latest developments on the ground.

Key facts

Cost: USD 1,083 billion

Size: 280 MW power plant, 125 m high dam and a storage reservoir

75% of the finance is planned to come from public sources:

- The Korean Development Bank has already (KDB) provided a USD 86 million loan.

- The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) has approved a USD 214 million loan together with an additional 5% equity share (USD 15 million) in early 2018, but as of June 2021 has not signed a loan agreement.

- The European Investment Bank (EIB) has approved USD 150 million loan in early 2018, but as of June 2021 has not signed a loan agreement.

- The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) considers USD 100 million.

- The Asian Development Bank (ADB) considers awarding the project USD 314 million.

Project promoters: JSC Nenskra, a joint venture of the Korea Water Resources Corporation & the Georgian state’s Partnership Fund

Contract type: Public-private partnership: BOT (Build, Operate, Transfer)

Contractor: Most recent news in the media reported that Hyundai Engineering & Construction (Hyundai E&C) and Limak have won a USD 737 million tender to realize the Nenskra project. Nenskra HPP’s previous construction contractor Salini Impregilo started preparatory works in September 2015 but abandoned the project in 2018.

Customer: Like many other newly built hydropower plants in Georgia, Nenskra is intended to produce winter season electricity for the domestic market and could export electricity, possibly to Turkey.

Key issues

In 2020, after 2 years of investigation, EBRD and EIB’s independent mechanisms found the Nenskra HPP project non-compliant with the standards of the two international financial institutions. The investigation was launched after complaints submitted to the EBRD and EIB CEE Bankwatch Network, Georgian NGO Green Alternative, and community representatives from the potentially affected areas.

The project does not meet the EBRD and EIB’s requirements in the following areas of human rights and environmental protection: indigenous people’s rights, the protection of cultural heritage, gender issues, assessment and management of environmental and social impacts, information disclosure and engagement of local communities and other stakeholders.

The Nenskra hydropower project foresees damming the Nenskra river 10 kilometers upstream from the village of Chuberi. To augment the reservoir, a 12.3 km long tunnel is intended to divert water from the Nakra river on the other side of the mountain, close to the village of Nakra.

The natural gem was first meant to be protected, but now stands to be scarred by the hydropower project. Read more >>

Despite being located in a geologically volatile region, the risk of avalanches, mudflows and landslides has not been properly recognised. Read more >>

With their own language, centuries-old traditions and customs, the largely isolated Svan communities demand to be formally recognised as an indigenous people to be able to protect their livelihoods. Read More >>

Concerns abound about the social impacts of the project, specifically on women, which have been poorly assessed. Read More >>

Local communities have taken to the streets to protest the Nenskra project. Read more >>

Nenskra is a dodgy deal that risks becoming a major financial liability for the country for years to come. Read more >>

Nature

Pristine natural gem – marked by majestic snow-capped mountains, adorned by old-growth beech forest, and inhabited by bears, wolves and lynxes – was first meant to be protected, but now stands to be scarred by the hydropower project.

The area where the Nenskra dam is planned to be erected, as well as the banks of both the Nenskra and Nakra rivers, are now adorned by black alder trees. Only few of them will remain if the project is realised as planned.

Various river habitats will also be irreversibly altered, not only at the site of the dam itself but also throughout the 17 kilometers downstream the Nenskra river, and the 9 kilometers downstream the Nakra river, as a result of the drastic changes in the water flows and sedimentation regime.

The reservoir that will form behind the Nenskra dam is expected to submerge around 200 hectares of the Caucasian beech forest on the surrounding mountain slopes. In fact, this unique habitat has already been damaged by newly paved access roads leading to the project site. The construction of the dam and additional roads will inevitably take an even heavier toll on this old-growth forest.

Moreover, the area slated for the reservoir – 400 hectares in total – is known as particularly important for the local population of brown bears which, like other local mammal species such as wolves and lynxes, are only likely to suffer serious disturbances throughout the construction of the Nenskra project and during its operation.

In addition, the increased and permanent human presence in an area that has been a wilderness since millennia poses an especially severe risk to the West Caucasian tur and the Persian leopard, two species already considered globally endangered, not least as a result of poaching.

The environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) for the project, which was supposed to account for the natural wealth in the area and hence be a key red flag, turned out to be wholly insufficient. An external review of the assessment report, commissioned by the Georgian environment ministry, determined it contains a range of insufficiencies and warned about the environmental price tag of the Nenskra project.

Still, after the project design has been heavily modified to meet requirements set by the international financial institutions backing the project, in February 2019 the Georgian environment ministry decided to waive the legal requirement for a new ESIA. Instead, the ministry ruled that the original, flawed ESIA remains valid. The following month two Geogian NGOs decided to challenge the ministry’s decision in court.

Recognising the need to protect this natural gem, in 2010 the Georgian government announced plans for designating the Svaneti national park, including the area where the Nenskra project is to be built.

This area, as well as other parts of the proposed national park, was even intended as an Emerald Site, under the Bern Convention, the European wildlife treaty.

Yet, in 2016 the Georgian government decided to dramatically shrink the area of the proposed Emerald Site, practically excluding those areas slated for the development of the Nenskra hydropower plant and multiple other hydropower projects, without even notifying the Bern Convention Secretariat.

The Georgian environmental group Green Alternative filed a formal complaint with the Bern Convention Secretariat, and in response the latter confirmed that “the site comprises some of the most pristine nature areas in Georgia.”

The Georgian government was then asked to propose alternative areas for the Emerald Site that could compensate for those excluded from the original plan. As of June 2019, this process is still ongoing.

The Upper Svaneti region is a geologically volatile mountainous area prone to landslides and mudflows. This natural hazard is even more pronounced at the site of the planned Nenskra reservoir and around Nakra.

The village has a history of mudlows that have already washed away the local cemetery and agricultural fields. The local residents have long been calling for protection measures, and they now fear that works on the Nakra river could cause flooding of their village.

In July 2018, the Chuberi community, closer to the dam site, has seen major floods damaging road infrastructure, devastating the homes of at least three families, and ultimately leaving the entire community “without … proper access to drinking water and electricity,” according to an emergency report of the Red Cross.

Members of the local community are worried this tragedy could repeat with works on the massive hydropower project in an area that is already geologically unstable. And they have a good reason to be concerned since the Nenskra project promoter has failed to undertake a genuinely comprehensive assessment of the geological, hydrological and seismic conditions around the project site.

In addition, there are concerns that works on the tunnel through the ridge between the Nakra and Nenskra valleys, that are planned to include blasting, could accelerate the degradation of the nearby glacier.

People

Sidelined throughout the process, local communities have mobilized to protest the Nenskra project.

Living within the Nenskra valley, the indigenous Svans have thrived for millennia, self-dependent and largely in isolation. The Svans make an ethnic subgroup of Georgia’s Caucasus mountains with their own language, laws and traditions.

The longstanding traditions in Svan communities in the region govern customary land ownership as well as decision-making and judiciary institutions such as the Lalkhor, the Councils of Elders.

Therefore, the Svans bear the characteristics of an indigenous people as spelled out in the International Labour Organisation’s Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention and several other international treaties.

But above all, the Svans identify themselves as an indigenous people. In March 2018, representative of 17 Upper Svaneti communities convened the Lalkhor in response to a string of development projects that threaten their livelihoods and the natural environment. In a milestone event, the council issued an official declaration demanding Svans are recognised as an ancient, indigenous, aboriginal, autochthonic people with appropriate rights for customary and community property in Svaneti. The declaration also called to stop the development of infrastructure projects, including the Nenskra hydropower plant, that do not have the local communities’ consent.

As an indigenous people Svans are entitled to certain protections that are formally recognised by at least three of Nenskra’s international financiers. Yet, so far these development banks have all failed to acknowledge the Svan’s indigenous status. In 2018, Green Alternative and Bankwatch lodged complaints with the grievance mechanisms of the EIB, EBRD and the ADB, requesting the banks apply their indigenous peoples standards in the Nenskra case.

As of June 2019, these complaints are yet to be resolved, and the Svans remain locked in a struggle for recognition as an indigenous people and the protections for their lands, culture and heritage that comes with it.

The livelihoods of approximately 1 000 people who live in the villages of Nakra and Chuberi are intimately linked to the natural environment as they rely primarily on forestry, animal grazing, and subsistence agriculture, and the Nenskra hydropower plant could compromise all types of livelihood in the area.

The massive project would entail a significant loss of agricultural lands and pastures that are customarily used by families or the community, and it could also change the micro-climate in the two valleys, thus altering the conditions enabling people’s livelihoods.

Such profound permanent changes would inevitably take a serious toll on the local economy – threatening to push local residents into poverty and marginalisation – and ultimately pose a risk to the traditional way of life the Svans have been nurturing since generations. Some local residents fear that the new reality will leave them no option but to move away.

In particular, as a 2016 study by Green Alternative and Both Ends found, women stand to bear a disproportionate brunt from building of the Nenskra hydropower plant. The project’s ESIA contains only a token paragraph on the gender aspect, which is essentially an aggregate, crude description of the current situation. The report authors note that the ESIA fails to assess any gender impacts the Nenskra project might have, including the various implications for the communities, and specifically on women of bringing in a large, male-dominated workforce for the construction of the project.

According to a report by the project promoter JSC Nenskra, 13% of the women in the two communities are farmers, 33% are housewives. While the company has been claiming the project would benefit the local residents through the creation of new jobs during the construction phase, it’s mostly men who would be recruited. And if indeed local men, who normally work in sustenance agriculture, will be employed in the project, the result could be increased workload for women substituting them on top of their current responsibilities. At the same time, women who sell nuts and berries they collect are concerned they could lose much of their incomes because of the project’s impact on the local forests.

None of these have been recognised by JSC Nenskra, neither has it proposed any meaningful measures to prevent or mitigate the impact on the local women.

Watch: In the shadow of the dam

Claims by the project promoter that the Nenskra hydropower plant enjoys wide public support are at odds with reality. From its inception, the project has increased tensions within and among Svan communities in the region. Numerous rallies have been organized over the past four years in Svaneti and in the capital Tbilisi to protest the heavy toll the project is set to take on local communities and the pristine nature.

More than 3,000 signatures have been collected in support of the Lalkhor declaration from March 2018.

Moreover, even though protests have been peaceful, opponents of the project have also faced intimidation. Senior politicians have repeatedly criticized protesters, arguing their actions are “meaningless”. Some locals have complained that they received threats prior to public meetings, specifically aimed to discourage them from carrying posters and banners or interrupting the public hearings in any way, and police forces have also been present at public consultation meetings.

Resistance to the building of the Nenskra plant has been escalating in tandem with growing protests against almost a dozen other controversial hydropower projects throughout Svaneti and beyond, and they are only likely to increase if local residents feel the project promoter, the Georgian government and the international investors continue to turn a blind eye to their objections to the project.

Hear from community members themselves

Echoes from the past

For many community members and civil society groups who have been witnessing Georgia’s unchecked hydropower development, the Nenskra project feels like a replay.

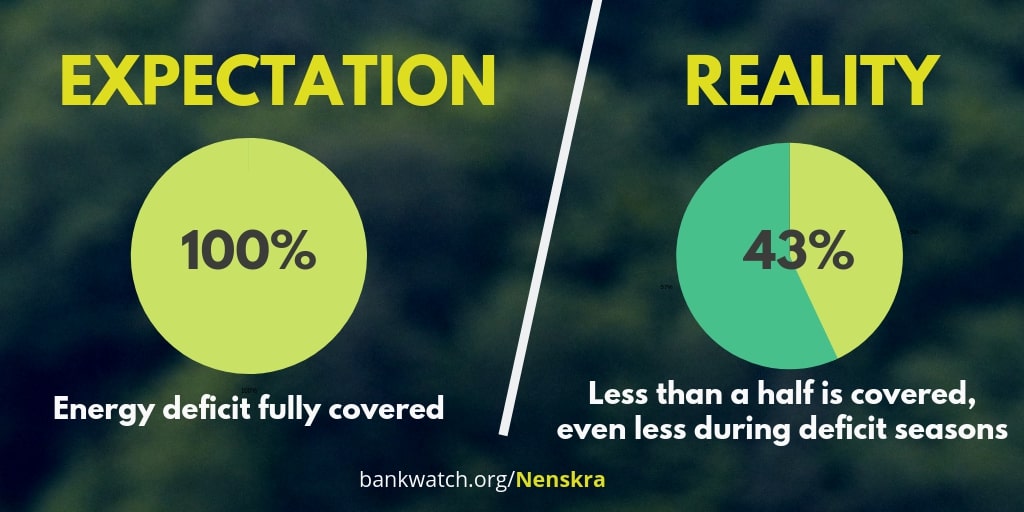

In fact, all hydropower plants in Georgia that were supported by international financial institutions don’t generate even half their capacity. These include Paravani, Dariali and Shuakhevi plants. In particular, the Shuakhevi plant, which was hailed as the harbinger of Georgia’s energy independence, hasn’t been operational at all since its construction was completed in June 2017. Rather, the project has been plagued with problems, including the failure of a diversion tunnel which the government is yet to investigate.

Like in the case of Nenskra, community members who feared the hydropower plant would have grave impact on their lives and the environment mobilized to protest the project. In at least one instance, their protest was met with aggressive police reaction under the watch of the energy minister himself.

In the village of Khaishi, half an hour drive from Chuberi, local residents stood in fierce opposition to the Khudoni hydropower that meant displacing 2000 members of the local Svan community. Construction of the project began in 1978 but has been delayed ever since.

Economics

The terms of this billion dollar project, including the electricy tariff the government agreed to, have been kept secret. But successive international reports and the leaked contract, revealed a dodgy deal that risks becoming a major fnancial liability for the country for years to come.

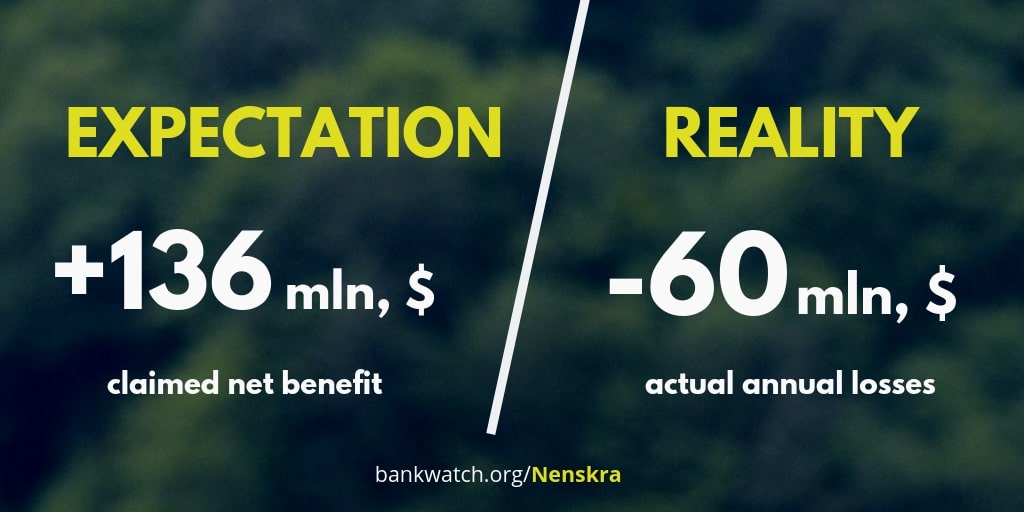

The Nenskra hydropower project, whose costs have already mushroomed to over USD 1 billion and are only likely to continue rising, has been marketed as a panacea to Georgia’s wintertime electricity deficits, and even as a cornerstone in the government’s ambitions to become a net electricity exporter.

It’s just that these claims simply don’t hold water.

In fact, the contract between the government and the project promoter JSC Nenskra, which includes the power purchase agreement and various other terms, has been kept secret. Until it was leaked to the media.

At the beginning of June 2019, a report aired on Georgian TV Rustavi 2, revealed that the project terms, as stipulated in the 2015 contract, stand in stark contradiction to what government officials and the various project proponents have been claiming until then.

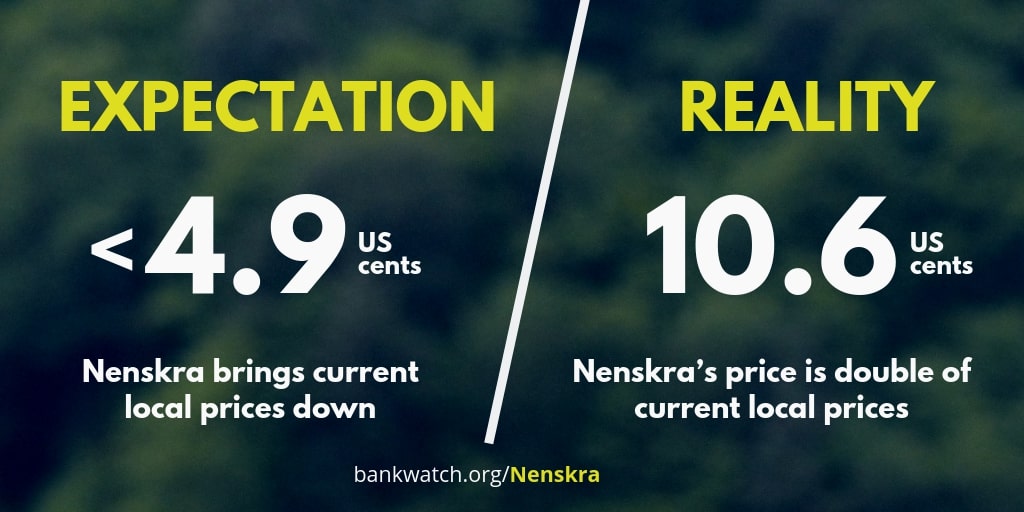

The figures in the leaked contract indicate that, the Georgian government had agreed to buy Nenskra electricity for 36 years for a price that is, on average, twice as high as the current tariff for domestic and imported electricity, and three times the price of exported electricity. Therefore, if the Nenskra hydropower plant is built and this agreement realized, Georgia’s public coffers stand to lose around USD 60 million every year.

According to the contract, the government has also committed to cover any losses to the company in case Nenskra fails to generate the anticipated amount of energy due to various hydrological reasons. This is not an unlikely scenario, given the projected impacts of climate change in the region, as well as the under-performance of earlier hydropower projects in Georgia (see box).

Warning signs about the financial viability of the Nenskra project have appeared since at least two years prior to the publication of the contract.

A July 2017 cost-benefit analysis commissioned by the International Financial Corporation on behalf of the Georgian government was the first indication that the government has committed to buy Nenskra electricity at a price that is almost double the wholesale price for electricity produced in Georgia and imported from abroad.

Then, the International Monetary Fund’s fiscal transparency report for Georgia from September 2017 sounded the alarm about the threat that the Nenskra project poses to the country’s fiscal stability, even in case the project is canceled.

And if that wasn’t enough, a leaked World Bank analysis from February 2018 warned that the project could become a severe liability and end up a heavy burden on Georgia’s public coffers. According to this analysis, between 2022 and 2041 the Nenskra hydropower plant alone would incur over EUR 1.8 billion in fiscal costs.

The report authors expect additional costs – beginning at EUR 113 million a year between 2023 and 2026 – due to exchange rate since electricity tariffs in the power purchase agreements that were examined used US cents, and the Georgian lari is anticipated to see depreciation. In addition, liabilities to Georgia’s electricity operator due to the energy surplus could reach USD 154.2 million by 2041, and the report authors also cautioned that the project’s costs could further increase with delays or unplanned expenses.

Nenskra’s project promoter JSC Nenskra counts on international financial institutions to cover up to three quarters of the project’s costs. But so far the vast majority of them seem pretty wary of chipping in.

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development has committed USD 214 million, together with a 5 percent equity share (USD 15 million), in January 2018. But nine months later, it announced it is “pausing the process” after it was revealed the constructor had abandoned it, dealing a major blow to the project. The European Investment Bank has also approved a USD 150 million loan for the Nenskra project in early 2018, but 18 months later the loan contract is yet to be signed.

In the meantime, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank will not decide on its USD 100 million loan before September 2019; and the Asian Development Bank, which considers awarding the project USD 314 million, is still in the process of examining it.

The Nenskra hydropower plant, which was initially meant to be completed by 2019, has key elements in its construction now scheduled to commence only in 2020, clearly indicating its price tag will continue to hike. This alarming information has been widely reported by Georgian media, demonstrating how overwhelmingly unsustainable the project is.

Key to this pandemic of pernicious hydropower projects in Georgia is the lack of national energy strategy. The government has been incessantly promoting projects that are poorly designed, sidelining local communities, and threatening sensitive ecosystems without even assessing the country’s energy needs and the cumulative impacts of these installations.

This oversight is particularly palpable in Upper Svaneti’s Enguri river basin, where the Nenskra project is planned as part of a string of massive hydropower plants including the 1300 MW Enguri dam, and the planned 702 MW Khudoni dam.

All in all, 34 new hydropower plants are planned in Upper Svaneti, an area larger than Luxembourg. This scale of development is coupled with additional infrastructure such as access roads, substations and high-voltage grids – all exacting a costly price on indigenous communities and unspoiled nature.

Latest news

Indigenous communities in Georgia threatened by a major hydropower project financed with European public money

Blog entry | 10 May, 2019There are many reasons why the Nenskra hydropower plant in Georgia should not be built at all. The project is set to have devastating environmental and social impacts, and its economics are particularly shoddy.

Read moreFive reasons why EBRD should pull out of the controversial Nenskra hydropower project

Blog entry | 8 May, 2019As the realisation of the project keeps dragging on, it is becoming increasingly difficult for the EBRD, and all international financial institutions involved, to justify their engagement.

Read moreGoldman winner to development banks: drop billion dollar Nenskra dam in Georgia

Press release | 29 April, 2019The 2019 winner of the Goldman Environmental Prize from Europe Ana Colovic Lesoska has today called on development banks – the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the European Investment Bank (EIB), the Asian Development Bank and (ADB) the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) – to drop their funding for the Nenskra hydropower project planned in Georgia’s Caucasus mountains.

Read moreRelated publications

Update to the Bern Convention on the Complaint No. 2016/09 – Possible threat by hydropower to “Svaneti 1” Candidate Emerald Site

Official document | 22 February, 2022 | Download PDFThe Svaneti 1 Candidate Emerald site in Georgia is threatened by the decision of the Georgian government to reduce its size for construction of the 280 MW Nenskra Hydro Power Plant (HPP) project. This is an update by the complainants on the Complaint No. 2016/9 – Possible threat to “Svaneti 1” Candidate Emerald Site who request an on-the-spot appraisal mission by the Bern Convention to Georgia, in order to investigate the threats to rivers that were recorded by Bankwatch during its fact-finding mission in July 2021.

Nenskra hydropower project: update

Briefing | 29 January, 2021 | Download PDFSince it was first proposed, the Nenskra hydropower project in Georgia has raised significant controversy and concerns among the indigenous Svan communities living near the proposed plant, as well as the general public in Georgia. The accountability mechanisms of the EIB, EBRD and ADB have found numerous violations of the lenders’ environmental and human rights standards, as well as violations of the rights of affected Svan communities.

Can the EIB become the “EU Development Bank”?

Report | 9 November, 2020 | Download PDFThis report analyses the EIB’s track record in the development field and offers a series of detailed recommendations for fundamental reforms at the EIB, so that the Bank can better support partner countries’ development priorities and ultimately become a credible candidate for the “EU Development Bank” seat.